Karnataka

The Tunnel To Nowhere? Decoding The Infra Tussle Between Tejasvi Surya And DK Shivakumar

Adithi Gurkar

Oct 31, 2025, 02:34 PM | Updated 02:35 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In the heart of India's Silicon Valley, a fundamental question divides policymakers, citizens, and urban planners: should Bengaluru invest ₹43,000 crore in underground tunnels for private vehicles, or channel those resources into expanding public transit systems that could serve millions?

On Tuesday, BJP MP from Bangalore South Tejasvi Surya walked into a meeting with Karnataka Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar. Surya emerged describing the encounter as "cordial" and "meaningful," noting they had discussed ideas and proposals to decongest Bengaluru, sustainable transport solutions, and the contentious tunnel road project itself. Yet beneath the diplomatic language lay fundamental disagreements about what Bengaluru needs and who it should serve.

The meeting amid the tunnel project row has crystallised two competing visions, each claiming to offer salvation from the city's crippling traffic congestion. On one side stands Surya, wielding data and international best practices to advocate for mass transit. On the other, Shivakumar defends the tunnel project, arguing that it addresses ground realities that statistics cannot capture.

Between these poles lies a city gasping under the weight of traffic paralysis, where commuters lose precious hours daily, and where every infrastructure decision carries consequences that will echo for generations.

The Case for Moving People, Not Cars

Tejasvi Surya's opposition to the tunnel road project rests on a foundation of comparative economics and transport planning principles tested across global cities.

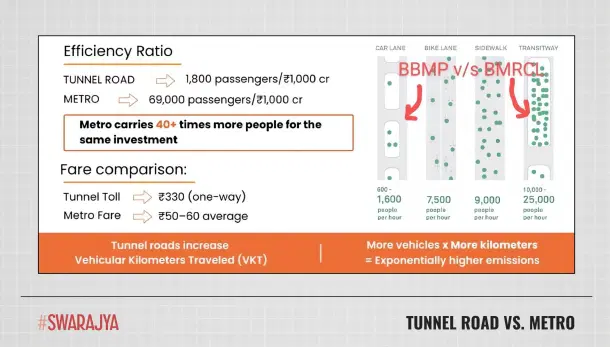

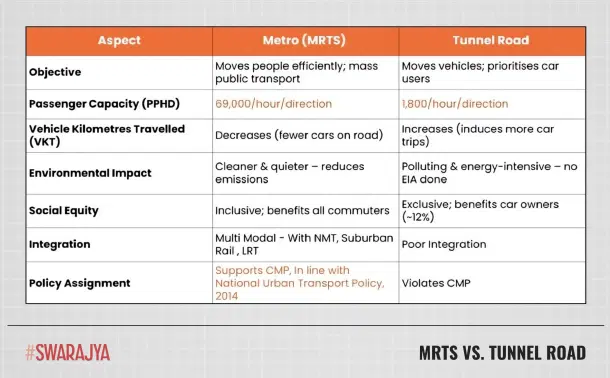

"If you spend ₹1,000 crore on tunnel road, you can move only 1,800 passengers," Surya argued. "But if you spend ₹1,000 crore on the metro, it would help transport 69,000 passengers, which is 40 times more beneficial."

The numbers form the skeleton of his argument, but the flesh comes from empirical evidence already visible in Bengaluru itself. The Yellow Line cut Silk Board traffic by 37 percent. The Purple Line further reduced it by 12 to 14 percent. Around 45 lakh people use BMTC services daily, with metro ridership reaching 10 lakh. These are not theoretical projections but lived realities demonstrating what happens when public transport infrastructure materialises.

Surya's critique begins with a stark accusation: instead of spending ₹43,000 crore on a tunnel road that would only help car owners move within a small corridor, the government could judiciously use these funds to set up over 300 kilometres of metro network and implement another 314 kilometres of suburban rail project. With such investments, he maintains, 70 percent of Bengaluru's population would use public transport.

His objection strikes at the project's fundamental premise. The tunnel road, Surya argues, cannot solve the traffic woes of Bengaluru as it would cater to a limited number of road users in a small area. He suggests that all phases of the metro rail project, totalling about 300 kilometres, should be completed at the earliest.

A Vision of Multimodal Integration

Surya's alternative vision paints a picture of a transformed Bengaluru: a city with effective zoning laws where people have access to workplaces, schools, hospitals, parks, and other amenities within a 30-minute radius. An expansive metro network of over 317 kilometres with trains arriving every three minutes. Buses of all sizes integrated with metro timings. A suburban rail network ensuring that, with all these public transport services, 70 percent of Bengaluru's population can commute on public transit easily and smoothly.

"Metro, Suburban Rail, Trams and Non-Motorised Transport are far more efficient, reliable and sustainable," Surya maintains. "They move people, not vehicles, and represent a better investment than an elite car-only tunnel road."

He advocates for modern trams that can carry between 12,000 and 15,000 passengers per hour with smaller turning radii and flexible operations. These trams can share corridors with other vehicles and complement metro and bus systems by providing continuous urban-level connectivity.

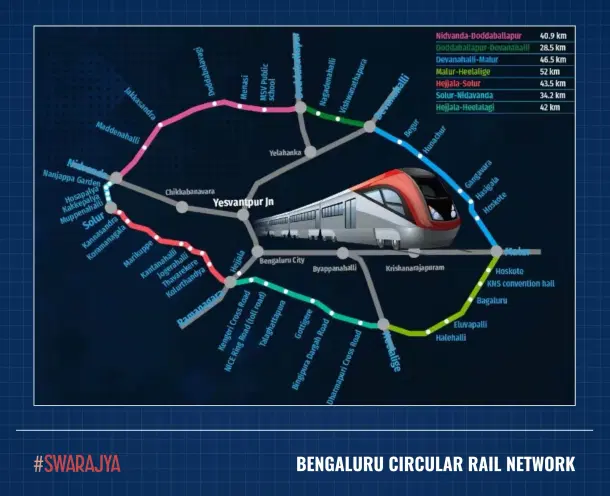

The Circular Rail Project proposed by the Government of India emerges as a sustainable step to link Tier 2 towns with Bengaluru in Surya's blueprint. This regional mobility network can reduce city pressure and support balanced urban growth across the metropolitan region.

The Priority Question

During his meeting with the Deputy Chief Minister, Surya presented an Alternative Sustainable Mobility Action Plan. His platform rests on clear principles: complete existing projects first, many of which are already delayed. Move more people in less time at lower cost, instead of increasing car traffic. Make public transport the top priority. Ensure Metro, BMTC, BBMP, and all departments work together. Build safer footpaths for pedestrians.

His immediate solutions include ensuring seamless urban mobility with a permanent budget for 1,000 new buses plus ₹1,000 per day support, approving ORR BRTS, fast-tracking Detailed Project Reports, implementing paid parking, clearing sidewalks, adding cycle parking at key spots, and launching Mission Great Roads and Mission Great Footpaths for a walkable city.

"No transport system can succeed without good roads and footpaths," Surya acknowledges. "The number of buses must rise to 15,000. Private participation should be encouraged to expand coverage so that every citizen can access a bus within five minutes anywhere in the city."

Fifty major junctions must be redesigned with pedestrian priority, better channelised turns, and modern signal timing, he proposes. Data-driven one-way systems should be introduced, and a joint committee must monitor intersection design and encroachment removal.

Potholes endanger lives and increase by over 60 percent every year, Surya notes. A Mission Sakkath Roads and Sakkath Footpaths programme using modern materials and technologies must be created to deliver pothole-free roads and walkable infrastructure for all.

Institutional Reform and Global Lessons

An expert-led single transport authority under BMLTA must be empowered to coordinate all agencies, Surya argues. A specialised Urban Transport Cadre under GBA and a digital mobility planning platform will bring accountability and evidence-based decisions.

His categorical rejection of the tunnel approach extends beyond this specific project. "Tunnel Roads and Double Decker Flyovers are short-term and unsustainable measures," he declares. "Expanding roads does not reduce congestion, it induces more traffic. The city must invest in efficient public transport that moves more people with fewer vehicles."

Bengaluru lacks a defined road hierarchy, Surya observes. Local streets directly feed into arterials like ORR and Bellary Road. A Street Network Plan must classify arterial, sub-arterial, and collector roads to balance traffic flow and reduce corridor overloading.

"Across the world, successful mobility systems are built around rail-based transport such as Metro, Suburban Rail and Trams," Surya notes. "They ensure reliability, predictable capacity and reduced congestion while improving environmental and social outcomes."

The Redundancy Argument

Rajkumar Dugar, Founder and Convenor of Citizens for Citizens, identifies what he terms fundamental "tunnel redundancy" in his analysis for Citizen Matters. "Approximately 90 percent of Tunnel 1, spanning from Hebbal to Central Silk Board, lies well within one kilometre of the proposed Sarjapur-Hebbal Metro stations," Dugar points out. "This metro line has already received approval from the Government of Karnataka and is awaiting final approval from the Government of India. Tunnel 1 will feature only three entry-exit points between its endpoints, whereas the Metro will have 10 stations in the same stretch."

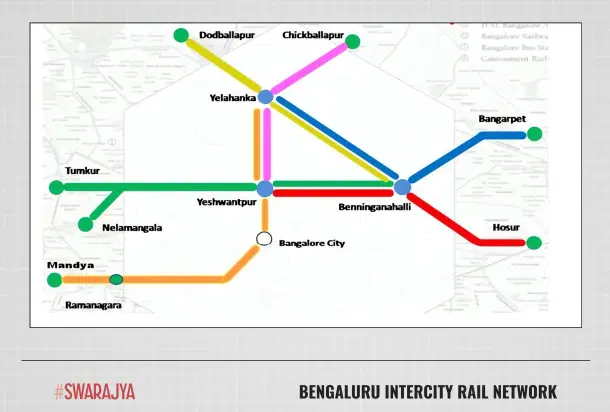

The proposed 28-kilometre Tunnel 2 between Krishnarajapuram and Nayandahalli presents an even higher case of potential redundancy. There exists a functional Metro line running Whitefield to Kengeri between the same two endpoints, and an upcoming Corridor 3 of the Bengaluru Suburban Rail Project, again between the same two points albeit with different alignment in between.

Ms Nithya Ramesh, Director of Urban Design at Jana Urban Space Foundation, diagnoses a deeper malady in Indian urban planning. "While we are all about road widening, they are about road tightening and improving the public space," she observes, contrasting Indian approaches with international best practices. "Often things like providing ramps, easing pedestrian movement, facilitating adequate lighting become not essentials but rather afterthoughts. This hyper-focus on vehicular mobility plagues all stakeholders from the local government, the traffic police and even the people."

Her experience working with city engineers across Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka reveals a consistent pattern. "When I work with city engineers across the board, their focus, even when on urban roads, seems to be catered to moving traffic like it's a highway. We are always looking at moving vehicle transport, rather than looking at the road as a conduit for movement and public space. It should be viewed as a facilitator of all kinds of transport and all kinds of activities."

The Affordability and Equity Question

The proposed tunnel road toll of ₹660 for a two-way trip becomes, in Surya's analysis, a symbol of exclusionary infrastructure. "When compared, Metro can move 40 times more people than a car tunnel," he argues. "Yet the proposed tunnel road toll makes it unaffordable and exclusionary. The project prioritises private cars over the mobility needs of the larger public."

Surya maintains that Metro is the lifeline for decongesting Bengaluru. It must be affordable, accessible, comfortable, and reliable. Reducing fares will make it a preferred choice for daily travel and help shift more commuters from private vehicles to public transport.

The Delay Risk

Delays in Metro construction slow the city's overall growth, Surya warns. The overlap between the proposed tunnel road and the Metro Red Line alignment could delay Metro construction by up to ten years and undermine the viability of mass public transport.

His proposal for the suburban rail is urgent. CMP 2020 targets 314 kilometres of Suburban Rail by 2031 with the potential to shift ten lakh daily commuters from road to rail. Immediate policy and financial steps are needed to fast-track approvals, land acquisition, and tendering processes.

Metro should connect the city's ends while modern trams support first and last-mile connectivity, Surya envisions. An immediate plan to operationalise this network has been presented. Integration between Metro, Tram, and Bus systems will create seamless urban mobility.

A Philosophical Stand

"The present approach of the government continues to be car-first," Surya argues. "The focus remains on road expansion without addressing first and last-mile connectivity. Fragmented planning and overreliance on roads are the root causes of Bengaluru's traffic problem."

His five-pronged alternative aims for 70 percent public transport modal share by 2031: improve execution of existing solutions, move people rather than vehicles, integrate all modes, implement the National Common Mobility Card, and prioritise pedestrians over cars.

"Bengaluru needs long-term vision, not short-term populism," Surya declares. "A city with multimodal integration, 300 kilometres Metro with three-minute frequency, a bus every five minutes, safe walking and cycling, and a city built around people not vehicles."

His ultimate vision: "What we must envision for Bengaluru is a global city built on ease of access, efficient public transport and equitable mobility. A city where every citizen can reach work, school or leisure using affordable public transport."

The Defence of Pragmatic Infrastructure

Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar's response to these criticisms carries the weariness of an administrator navigating between idealistic visions and stubborn realities.

"He gave a few suggestions. He said instead of a tunnel road, a Metro line should be built," Shivakumar acknowledges of his meeting with Surya. "We are already working on Metro construction, but we need funds too, right? He also suggested allowing private buses and introducing BML feeder buses. I asked how much money has come from Delhi. I told them I will also come, meet the Prime Minister, and get funds sanctioned."

Following their meeting, Shivakumar said Surya had given him a presentation. "He had some suggestions and a PPT; I have asked officers to look into it," he told reporters. However, he expressed scepticism about the practicality of some proposals. The traffic congestion in the city is already severe, he noted, and he questioned how allowing more buses would solve the problem.

The Social Reality Argument

Shivakumar's defence of the tunnel project rests not on rejecting public transport but on recognising what he sees as unchangeable aspects of urban Indian society. "Can I stop you from bringing your vehicle? It's a matter of social responsibility. People prefer to travel in their own vehicles with their families. Can we prevent them from using their cars?"

His controversial observation about marriage and car ownership revealed assumptions underlying his position. "If you don't have a car, you won't get a bride at home, that's the mindset," Shivakumar stated, elaborating: "Today, people even hesitate to marry their daughter to a boy who doesn't own a car."

He argued that Surya doesn't understand the social obligations behind people buying cars. "If needed, MPs can appeal to their constituents to leave their cars at home and use public transport. Let us see how many actually follow that."

"How many people travel by bus anyway?" Shivakumar questions, his rhetorical challenge pointing to behavioural realities. "For everyone, status matters. Even officials travel by car."

Whether one finds this observation offensive or honest, it articulates a reality that transport planners cannot wish away. In contemporary India, vehicle ownership represents more than mere mobility. It signals economic status, family responsibility, and social standing.

The Project's Stated Objectives

The proposed tunnel road, as articulated by government officials, aims to ease Bengaluru's traffic by creating an underground route linking key parts of the city. Officials maintain it will help decongest busy roads, reduce travel time, and offer a quicker route for commuters struggling with the daily traffic burden across major corridors.

The project's stated objectives are comprehensive.

Objective: The primary goal is to significantly cut traffic congestion, reduce daily travel time for commuters, and lower fuel consumption along major city corridors by providing a faster, safer underground route.

Route and Design: The tunnel alignment is designed to pass deep beneath central Bengaluru and core city areas, ensuring minimal surface disruption. It is planned to integrate seamlessly with the city's existing metro routes and key surface transport networks.

Impact on Lalbagh Park: Authorities have provided assurances that the iconic Lalbagh's green cover will remain unaffected. The tunnel will run deep below the garden, with only one acre of land being used temporarily for construction equipment, which will be fully restored afterwards.

Construction Approach: The project is deemed technically feasible and will employ modern boring technology and strict safety guidelines. Officials emphasise the use of eco-friendly tunnelling practices to control noise, dust, and vibration levels.

Oversight and Public Involvement: Expert teams from horticulture, geology, and urban planning will monitor all stages to protect heritage and ecological integrity. The government also plans to hold public meetings and consultations to shape the final project design and ensure transparency.

Legal and Environmental Assurances

When the Karnataka High Court heard a petition filed by city-based actor Prakash Belawadi opposing certain aspects of the ambitious project, the state government informed the court on Tuesday that trees in Bengaluru's Lalbagh are not being cut for the twin tunnel road project.

While a group of Bengaluru residents had already moved the court raising similar issues, including the tender process and approvals for the project, Belawadi's petition specifically opposed any alienation of Lalbagh's land by the horticultural department and also called for a geological impact survey.

During an earlier hearing on 25 October, advocate and BJP MP Tejasvi Surya represented Belawadi, raising concerns about the road project's impact on 6.5 acres of Lalbagh's land as well as a three-billion-year-old rock formation within the garden.

The Tunnel's Technical Specifications

The tunnel is not just 18 kilometres long, as Surya points out in his critique. The DPR shows ramps extend the corridor to nearly 20 kilometres. These 22 choke points, according to Surya's analysis, will create multiple congestion hotspots and worsen the city's traffic conditions further. This becomes part of the technical debate between proponents who see the tunnel as a solution and critics who see it as potentially creating new problems.

A City at the Crossroads

Bengaluru's tunnel road debate ultimately poses questions that extend far beyond infrastructure choices. It asks what kind of city Bengaluru wishes to become, and who gets to decide.

Will it follow the path of Singapore, Tokyo, and Seoul, cities that invested heavily in public transit and now enjoy both economic vitality and liveable streets? Or will it pursue hybrid models that attempt to serve both private vehicle users and public transport commuters, risking the possibility of serving neither well?

Can a democracy reconcile competing visions when both claim to serve the public interest, one through expanded mobility choices rooted in global best practices, the other through respect for existing preferences and social realities?

The ₹43,000 crore at stake represents more than money. It represents a choice about whose mobility needs matter most, which vision of urban life should prevail, and whether Bengaluru can escape the trap that has ensnared so many developing world cities: building infrastructure that solves yesterday's problems while creating tomorrow's crises.

As expert teams prepare reports, courts hear petitions about Lalbagh's protection and geological formations, and citizens debate on social media, one reality remains inescapable. Whatever decision emerges will shape Bengaluru's trajectory for the next half-century.

The tension between Surya's data-driven advocacy for mass transit and Shivakumar's pragmatic acknowledgment of social realities captures a broader struggle in India's urban future. Both perspectives contain elements of truth that cannot be easily dismissed. The technical superiority of metro over tunnels is mathematically demonstrable. The social dynamics that drive car ownership are culturally undeniable.

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth is that both visions may be right about their diagnoses while disagreeing about prescriptions. Surya correctly identifies that car-centric infrastructure creates induced demand and fails to move masses efficiently. Shivakumar correctly observes that current social dynamics resist the behavioural changes required for public transport dominance.

What remains certain is that the decision cannot be delayed indefinitely. Every day of inaction means more hours lost to traffic, more fuel consumed in gridlock, more citizens questioning whether India's Silicon Valley can solve its most basic urban challenge. The debate between Tejasvi Surya and DK Shivakumar, with all its technical complexities and social dimensions, ultimately asks whether Bengaluru will build the city its residents need or the city its residents want, and whether those two visions can ever truly align.

Adithi Gurkar is a staff writer at Swarajya. She is a lawyer with an interest in the intersection of law, politics, and public policy.