Legal

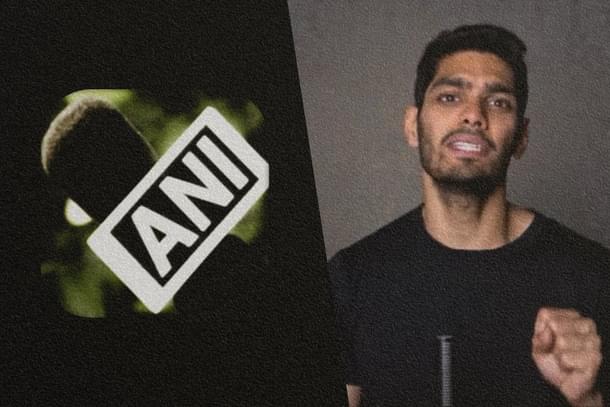

Copyright Strikes And Fair Use: What Mohak Mangal v. ANI Reveals

Arushi Bhagotra and Ananth Krishna S

May 27, 2025, 09:29 AM | Updated 09:29 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Debate over copyright, fair use, creative commons licensing, public domain, transformative use, and so on have erupted overnight on X (formerly Twitter). It was sparked when prominent YouTuber Mohak Mangal revealed that he received copyright ‘strikes’ on his YouTube Channel from news service ANI.

In a widely circulated exposé, Mangal revealed he received two copyright strikes from Asian News International (ANI): the first for using a 10-11-second news clip in his analysis of the R.G. Kar rape case, and the second for a 9-second ANI clip in his video on Operation Sindoor featuring Defence Minister Rajnath Singh.

For this brief use of otherwise publicly available videos, the YouTuber was given an ultimatum from ANI to pay ₹45–50 lakh for a license or risk losing his channel entirely, as three ‘strikes’ would mean permanent deletion under YouTube’s Terms of Service.

In another related incident, an anonymous creator was similarly hit with multiple copyright strikes and told to pay ₹15-18 lakh to withdraw them or face permanent channel deletion. The issue has obviously led to social media outrage against ANI, copyright ‘strikes’ and calls for the Central Government to intervene.

How YouTube’s Content ID Became A Private Judge, Jury, And Executioner

This issue is a result of how YouTube’s global Content ID system works.

The Content ID system is an automated digital fingerprinting technology that scans every uploaded video on the platform against a database of copyrighted material provided by rights holders, enabling copyright enforcement. Content owners like ANI can automatically claim, monetize, block, or track videos containing their content, often without human review.

However, this system is largely blind to ‘fair dealing,’ a recognised usage of copyrighted content internationally. YouTube has essentially tried to mitigate the nightmare of enforcing copyright on its platform through the Content ID system, which by and large, does work considering the legal position of copyright.

To understand what has happened in the case of Mohak Mangal, both copyright law and YouTube’s Content ID system has to be understood.

In simple terms, YouTube has coped with the issue of copyright by creating a system that allows a set of recognised copyright holders to enforce their rights through the Content ID system.

YouTube checks videos uploaded on its platform for possible infringement of copyright, and notifies the relevant holders of the same. The copyright holder then has the option to block the video, monetize it by claiming advertisement revenue, or request the entire video’s takedown, actions that have immediate and severe consequences for the creator in case of issuance of multiple strikes.

Outdated Laws, Automated Systems: Copyright In The Age Of The Internet

The framework for copyright is something that has been standardised across jurisdictions through the Berne and the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”) Conventions. While there are procedural differences and nuances in how copyright or other intellectual property rights are enforced in various countries, there is a fair amount of consensus on them.

Copyright and the parameters of fair use evolved in the pre-Internet era; there have been no major updates to them since then. The legal standard of protecting ‘original work’ of a creator was that an unauthorized person, whoever they may be, cannot exploit the same without the original creator receiving some tangible benefit.

The idea here is that the benefit cuts both ways: the author of a creative work should have the right to control and profit from their creation, while companies or entities that own rights to certain works (such as news agencies or studios) also have legitimate interests in managing and monetizing their intellectual property.

Given that YouTube hosts thousands of hours of user-generated and copyrighted content every minute, it is logical that the platform has implemented automated systems like Content ID to help manage and enforce these rights at scale.

This approach is designed to balance the interests of individual creators and large rights holders in a digital ecosystem that is far more complex and voluminous than anything the original copyright frameworks envisioned.

Copyright Cuts Both Ways

Whatever ANI has done, however, is not unprecedented. Major global rights holders such as Nintendo and Warner Music Group have long been known for aggressively enforcing their copyrights on platforms like YouTube, often issuing takedowns or demonetization claims on videos that use even brief snippets of their content.

Popular educational creators like CGP Grey have also sought to enforce their copyright by issuing copyright strikes against a content creator who used their video for ‘reaction content.’ That example is, in fact, a good illustration of how copyright management systems like Content ID can help content creators too.

Many YouTubers have used the system to take down content of channels on the platform that are re-posting or completely ripping off their content. In fact, YouTube is reportedly even testing a tool that can flag ‘AI Likenesses’ of content creators on its platform.

Considering the magnitude of User-Generated Content, tools like this or measures like Content ID are crucial not just for corporations but for individual content creators as well. After all, copyright protects these creators whose rights may be infringed.

The issue, then, is not linear: it cuts both ways. Rights holders are justified in protecting their intellectual property, but the automated and often heavy-handed enforcement can stifle creativity, commentary, and education.

However, it is crucial that fair dealing (or fair use) is given due consideration, so that creators who genuinely add value through commentary, criticism, or transformative use are not unfairly penalized.

YouTube’s Content ID system, which allows rights holders like ANI to flag content and issue strikes, often disregards these nuances. Fair dealing under Section 52 of India’s Copyright Act, 1957 permits limited use for criticism, commentary, or education. The lack of clear guidelines on permissible usage such as whether a 10-second clip in a 20-minute analysis qualifies creates a grey area that ANI has exploited, demanding ₹10–25 lakh to withdraw strikes.

For “Sumit,” paying ₹15–18 lakh was ultimately cheaper than contesting the matter legally, setting a troubling precedent that monetizes legal uncertainty.

Fair Dealing Caught Between ANI’s Legal Rights And YouTube’s Content ID Mechanism

ANI’s crusade exposes the obsolescence of 20th-century copyright frameworks in a digital era defined by democratized content creation. Traditional intellectual property rights assume a clear divide between producers and consumers, but YouTube thrives on transformative content like commentary, remixes, and analysis that blurs these lines.

When creators like Mohak Mangal use a 10-11 second ANI clip, their original analysis is also copyrightable, yet YouTube’s system prioritizes ANI’s claim and often dismisses the creator’s contribution.

The threat of channel termination under YouTube’s “three strikes” rule, combined with the high cost of legal recourse, forces many creators to comply with ANI’s demands or abandon their work entirely. It would not be unfair to consider this an unethical and coercive business under the guise of a legal process.

This is made clear in the clip shared by Mangal, where the demand from ANI is made for ₹40 lakh, of which ₹5 lakh is for each of the eight or so violations, with him receiving a 2-year ANI subscription in return. ANI is well within its rights to demand compensation for the supposed copyright infringement by Mangal, but the pattern of issuing two “strikes” and then leveraging it for a penalty would not be what is envisioned within the framework of copyright law.

A demand to secure an annual subscription for the license of ANI’s content or applying for a revenue share would have been a more prudent outcome for ANI in the situation than demanding excessive amounts as “penalties.” This is made even more clear by the fact that the supposed copyright violations by Mangal are for a minimal amount of time within the videos posted.

Not Much The Government Or Anyone Else Can Do

The problem, however, is that the Central Government’s hands are tied in resolving this issue. The issue involves private parties: ANI, the copyright holder, YouTube’s Terms of Service enabling ANI, and the content creator.

Beyond the platform’s appeal process, creators’ only recourse is to seek judicial determination of whether their use constitutes “fair dealing” under India’s Copyright Act, 1957. This question falls squarely within the judiciary’s purview, not the Executive’s, and requires no legislative intervention, as India’s copyright framework aligns with applicable international standards.

YouTube’s Content ID has been developed with the idea of dealing with a multitude of jurisdictions and is not limited to India or the US. The copyright enforcement and appeals system is the same worldwide. If fair use (or in the alternative, fair dealing) issues have to be accommodated in a more structured manner for YouTube, the same has to come across through international consensus. Similar copyright battles are erupting worldwide, highlighting a universal disconnect between outdated laws and the realities of today’s participatory, remix-driven digital culture.

ANI’s behaviour is also not the norm. Agencies like IANS and PTI adopt a more collaborative approach, such as flexible licensing or attribution-based usage, fostering partnerships with creators. These agencies probably factor that short clips in viral videos or social media reels enhance their reach and relevance.

ANI’s approach risks straining relationships with India’s digital creators, the YouTubers, podcasters, and influencers, who basically amplify their brand to massive audiences.

Through this episode, ANI has likely burnt opportunities for it to collaborate with content creators and given an open invitation to news agencies like IANS, whose content and brand may be utilized by content creators. The apparent effect may be small, but it can still have a disproportionate impact on public image, like it already has.

Beyond ANI: Copyright’s Collision Course With The Future

Copyright meanwhile, not only faces issues with respect to enforcement online in platforms like YouTube, but the artificial intelligence revolution has raised even more concerns. Large Language Models (“LLMs”) by OpenAI, Claude, and other organisations are reported to have used copyrighted content to train their models.

Multiple suits are pending against these organisations for alleged copyright violations, including one filed by ANI against OpenAI, alleging that its copyright has been violated.

It may very well be easy to cast ANI as the villain and Mangal as the hero in this episode. But the reality is that copyright and its enforcement is a complex issue that can be reduced to dichotomies, and no easy solutions exist to the questions raised.

ANI’s claims may not be held up in court and may be an excessive, unethical, or coercive business tactic, and YouTube might not be accounting for fair dealing under the law. YouTube, too, is only accounting for the messiness of enforcing copyright on its massive platform with millions of hours of user-generated content.

The fact that Mangal makes an invocation to the Prime Minister’s Office and the Minister of Information and Broadcasting is a telling attempt to underpin some sort of political aspect to this issue when the entire episode is about copyright and its enforcement on a global platform by a media agency. This ultimately is a disservice to the issue of fair use or fair dealing in copyright and Mangal’s experience.

Arushi Bhagotrais a legal consultant. Ananth Krishna S is a lawyer and observer of Kerala’s politics.