Magazine

Meet Padma Shri Sukri Bommagowda, An Ambassador Of The Singing Tribe Of Halakkis Who Fears Her Folk Treasures Will All Vanish With Her

Harsha Bhat

Mar 08, 2019, 11:03 AM | Updated 11:03 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Sukri ajji is sad — sad that her songs, saree, and strings of beads will all go with her. The wrinkles on her face that only multiply every time she breaks into a giggle, recollecting the compliments she got from all the ‘big people and stars’, are a testimony to the eight decades of her life as a proud and caring custodian of her folk culture.

As I landed in Ankola, a coastal town of Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka, and headed to Badigeri village therein, we asked for Sukri’s house, only to be asked “which Sukri?”. “Padma Shri Sukri, the one who sings,” I said. ‘Sukri’ is a very common name in the Halakki tribe, a boy born on Friday would be named Sukru, and a girl, Sukri. Such are the ways of this tribe that personifies simplicity.

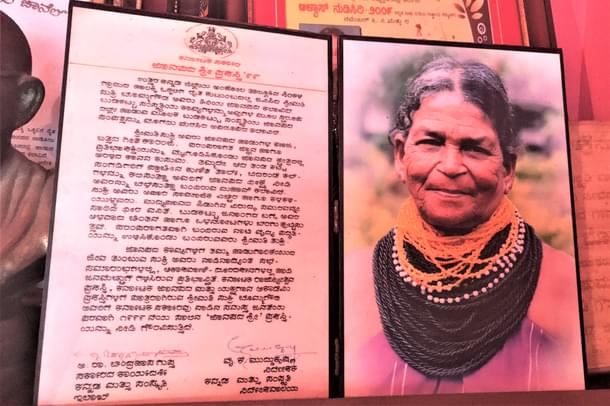

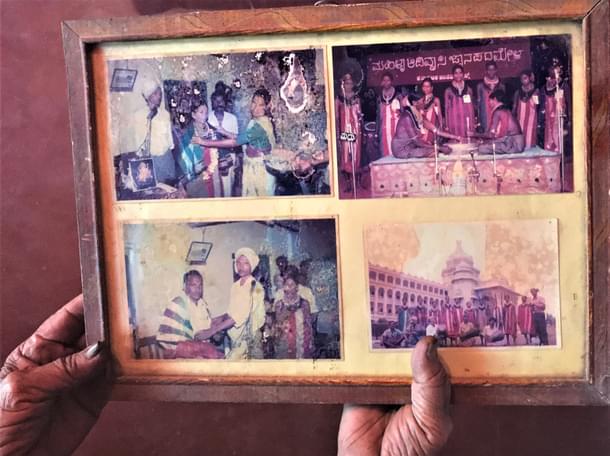

A tiny mud road through hutments, with hens running around, and a lady walked me to Sukri’s house. There she was standing meek and humble in a living room, whose both walls had shelves that run from the floor to almost the ceiling and were packed with awards, and felicitations and trophies. She tries to hunt for a book in which she remembers someone having written down her songs, in an adjacent room, which is also laden with awards. But if you were to meet her when she was busy with her daily chores, it is hard to imagine this lady, wearing an old and faded saree in the traditional style of the tribe, was one who had lost count of the awards she has received.

Padma Shri Sukri Bommagowda brought her tiny hamlet and her tribe in the town of Ankola fame that one could not imagine possible for a woman who barely can sign her own name. She was busy fetching firewood even as they announced her name among the list of Padma awardees last year. Over half a century of accolades has changed nothing for the 85-year-old, who has a song for every season, some for no great reason.

“For everything, there is a song. How can there not be?” asks Sukri ajji. “From birth to marriage, to death, to festivals, to daily chores like fetching water, or farm work like harvesting, we have a song for everything we do,” she adds.

Rightly called the “nightingale form the Halakki vokkaliga community”, Sukri ajji can sing thousands of songs. She also composes new ones for various occasions, has used her songs to drive home social messages and to serve her in her activism. From ‘women safety’ to ‘fight against alcoholism’, she is a ‘song bank’.

As I sit down to talk, she looks tired. “I was unwell, but I am better now she says,” as she sits down holding the chair firmly with her bare arms, which are a testimony to all the years of hard work she put in at the fields and in her fight for various causes.

“Do you still sing ajji? Will you sing?”

“A line or two I can recite for you, maybe,” she says. The reluctance had me disappointed for a moment. But it was a good two hours, when the auto rickshaw driver, who had been waiting for me to finish my interview in half-an-hour, came by and said “it’s been two hours, I can come back later if you will be long.” Time had passed in the tales that Sukri ajji wove for those two hours. Her initial reluctance had vanished the minute she started singing.

She inherited the songs from her mother Devamma, and one of the first songs she recollects is the one the tribe sang on tulasi puja. Every single ritual of the puja, of various offerings, of how the tulasi is decorated and worshipped by the Halakkis is explained lyrically.

Recollecting her foray into singing formally as a folk artiste almost six decades ago, she remembers when researchers Nage Gowda and others had come along asking her to render some folk songs. “I said I would make a cassette and give it to them and they could do a sound check and then see if it works,” says ajji, breaking quickly into the first song she had sung for them. That is when she got a group of women and tutored them in singing the traditional songs.

“When asked by the researchers, ‘What else do you do apart from singing?’ I told them pagade kuniyudu, (dancing the pagade) taarle kuniyudu (dancing the taarle), so they asked me why do we dance the ‘taarle’. It's awaiting and calling the rains when the earth has gone dry and barren I told them,” ajji said.

She sings the lines and the chorus resounds ‘taarle… taarle’, she demonstrates from her chair.

“The four women danced and sang the chorus while I sang the song for the taarle dance,” she says as she breaks into a song yet again.

“Oyyoyoi maleye nammoorgei..

Chorus: Taarlei

O yyoyoi maleye nammoorgei..

Taarlei

Nammoora makki Katthi batthi hwadu

Taarle

Dodd maLey barli

Taarlei

Dodd kere tumbli

Taarlei...’

Every line wishes for the rains to come and ensure the land flourishes. “May there be a big rain, may the big lake be filled up, may the stalks smile, may the fields go lush green…” and so on.

“When the earth is awaiting rains, it is a ‘maja’ to dance the taarlei,” she says and giggles like a little girl, her teeth shining through her freckled lips.

That she had an early marriage to a much older person, or that she had lost both her children, or that her brother’s son she adopted also drank himself to death, or her ill health or age, none of these are part of the conversation when you ask her about her journey. She is more concerned that the likes of her granddaughter are sporting clothes “like you only”, she says pointing at my salvar kameez. “They do not want to continue our traditions, our youngsters don’t sing, don’t wear our sarees as we do, and no strings of beads… it will all go with me it looks like,” says a visibly upset ajji.

Uneducated Teacher

Often called the last and lone voice of this singing tribe, Sukri ajji has been a social warrior in her own right.

Married off very early in life, she didn’t have the fortune of education. “There was no school in my appa’s place. Moreover, we had to work, carry segani butti (cowdung pans) so we couldn’t think of studying, which is why I have always campaigned for education. I never went to school, but now when they ask me to inaugurate I keep going,” she laughs.

She is the chief guest and asked to address most schools in the vicinity, the local authorities call on her for various campaigns, especially the likes of fighting against alcoholism and women’s rights which she has been a crusader for many decades now. “When I attend many big functions, many people talk, but they mainly talk about themselves. Should they not be talking about the issues or the people that need to be addressed? I always wonder what the point is in talking about their own work and selves,” asks ajji in stern and simple words. From addressing the issue of ‘should acacia trees be grown?’, ‘importance of education’ ‘advent of Konkan railways’ to ‘tribal herbal medicines’ ajji has an answer for everything from her kitty of folk wisdom.

“Acacia trees can be grown, but what we need are our own local varieties. Acacia doesn’t let other grasses grow nearby so what will the cattle feed on, moreover all the wells and ponds nearby will dry up, so we could be better off growing local ‘old’ trees. Isn’t it?”asks ajji.

Recollecting her interactions at schools and colleges she says, “at the schools especially, everyone asks questions, every single person has questions, and they ask me,” her simplicity only adding beauty to that smile of hers.

None of those who inhabited the village when she came here as a bride all of 14 years are around, but life has come a full circle for Sukri ajji. Someone who had stepped out of her hamlet for the first time to move to her husband’s house, today has been to the nook and corner of the country taking along with her the folk vibrance.

She is unstoppable as she recollects her visit to Kannada superstar Dr Rajkumar’s house when “Rajkumar’s children were still small” and telling actor Shivarajkumar of the same in recent times when she met him after the veteran actor’s death at politician Madhu Bangarappa’s place. She breaks into a famous Rajkumar song and goes, “arey hoi arey hoi… I can still remember his smile as he sang, maja maja mathadidru (it was fun talk)”.

What next? Who will bear the torch of folk culture that she has been carrying for the last six decades? “Many like you, students of folklore and the like come and write down and document a song or two, but our own children don’t sing. It will all go with me, my strings of beads and songs. Who wears these beads now? But they don’t get it, no jewellery they sport can match the feeling of wearing our traditional beads, it is just not the same,” her pride clearly changing the tone of her voice. “It was the simplest identity marker. Who are the Halakkis, what kind of people are the Halakkis, all this was reflected in our clothes, our songs, but alas, not anymore. Everyone looks like anyone else,” ajji complains.

She demonstrates their way of wrapping the pallu of the saree (the Halakkis wear no blouse) whose end is rolled thin, has a thread attached which is taken over the chest under the arm, taken around the neck, down the right shoulder and tied back to the portion near the chest. The heap of bead strings are then worn on top, which is said to help them keep their necks erect as they carry the stack of firewood on their heads etc. “But all this is now gone. Youngsters are only sporting jeans pants, and sarees are also worn with blouses as others do,” says an unhappy ajji.

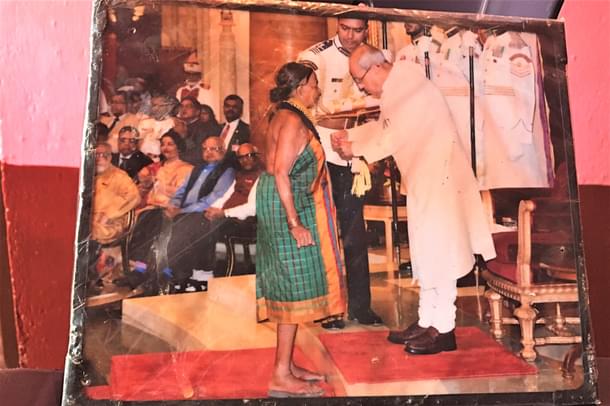

She has been striving to get her tribe recognition. “All these awards mean nothing if they don’t do anything for my people, right? I told Modi ji also, that this Padasiri (Padma Shri) is fine, but I would be happier if my folks got SC/ST status,” says ajji, as she shows us the photograph of her receiving the Padma Shri from former president Pranab Mukherjee.

Sukri ajji is the best testimony to the fact that rootedness, and taking pride in one’s own culture does bring as much applause, recognition and success than any fancy degree from any university would, for she has lost count of the awards that she has received and the number of lives she has touched. Like she puts it plain and simple, “if we give up what is ours, slowly but surely we too shall vanish”.

Harsha Bhat is an author, linguist, content strategist, and a compulsive chronicler of Bharat's civilisational heartbeat.