Magazine

As Men Make Way For Machines, Many Jobs May Vanish

Rajeev Srinivasan

Dec 13, 2017, 12:44 PM | Updated 12:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On a May trip to Paris and the San Francisco Bay Area, one of the things that startled me is the virtual extinction of various categories of jobs. Technology could well be the culprit, although I read somewhere that only a single official job classification has explicitly disappeared in the United States in the last 60 years: elevator (lift) operator. But what I observed was that there is an accelerated pace at which some formerly ubiquitous jobs are disappearing. Perhaps the same will happen in India, too.

I discussed this with a banker, chairman of a large private bank, and he was sanguine: he pointed out that in past cycles of job disappearance, other positions opened up to compensate. If bank teller jobs have been decimated by the appearance of ATMs and internet banking, he pointed out that the proliferation of television channels had created vast numbers of new positions. Implicit in his statement was the assumption that people could be re-trained and re-purposed.

That assumption may not be valid: often, even if the total number of jobs increases, a significant proportion of those who lost their positions are unable to find new jobs that are more or less comparable to their old ones. Skills are often not transferable; or they may be forced to take up jobs that pay significantly less. That was the experience of manufacturing workers in the US when factory jobs disappeared: many ended up being forced to take up much worse service jobs, for instance slinging hamburgers in fast food joints.

The reason I spoke to the banker was that it is my hypothesis that many jobs that are permanently disappearing in the West are cash-handling jobs. In the last three or four years, I have seen a massive shift in the US at least away from cash: even for small transactions like $10, I now find people are routinely using credit cards. In fact, I was a little apprehensive that my $100 bills would be hard to break, and indeed that was true at a Walgreen’s I went to: they had a sign saying “No bills larger than $20, please”.

It does make sense to reduce the use of cash: as we have been told during demonetisation. In the US, especially for small businesses and consumers, violent armed robbery could well be a factor. In addition, it is a well-established fact that people spend more lavishly with credit cards than when they have to dig up cash. Besides, the time taken to complete a cash transaction, including the consumer fumbling in his pockets for loose coins, and the cashier counting out the change for the purchase, all that adds to the cost.

In a sense, the retail efforts of demonetisation are what I’m alluding to. In the US, they seem to have achieved de facto demonetisation, which means you don’t need so many people to handle cash. The next stage is to automate other things that customer-facing people currently do: which would be providing information and advice, as well as taking orders. These things are also happening.

I am familiar with the idea of self-check-in at airports in India. But in San Francisco and Paris, it has now gone one step further: you get to print out and attach your baggage tags as well as your boarding passes. The check-in agent merely weighs your bags and checks your id. I am pretty sure you will soon have to weigh your own bags and have your id checked (biometrics, anyone?) by a computer.

What this also means is that airlines are economising on ground staff. We had an interminable line that took more than an hour to clear for Air France to Paris from San Francisco. It was annoying and frustrating, but surely it was worse for the lone at-large agent who was bombarded with queries by irritated people, enough to fill an Airbus A-380, waiting in line. At least in this instance, automation is forcing customers to do more, wasting their time, and annoying them, but of course it’s costing the airline less money.

I found other examples of these disappearing jobs in the public transport system. I went to the Palo Alto train station to take the train to San Francisco, about an hour away. I walked into the building with the ‘Southern Pacific Railroad’ logo on it, only to find that it had become a cafe! I asked a staff member where I could get information about the trains, and she told me, redundantly, that it was a cafe and that I could get my tickets from the machines outside.

The fact is that I had noticed the machines, but I wanted information too: about schedules, and whether I could buy a combined train-bus excursion ticket for the day. When I had lived there a while ago, I used to commute by the same train to San Francisco for work, and I had a combined bus-rail pass. Of course there was no way of finding out about this, and so I just bought a train ticket from the vending machine using my credit card.

As for schedules, there were no printed brochures available, and I had to download them to my phone (probably a good thing, I admit). On arrival at the San Francisco station (which I remembered as 4th and Townsend, but now it’s 4th and Kings), I realised there was no human to help explain which trolley car or bus to take to go to Powell and Mission, where I wanted to get on the famous cable cars. No touch screens either. Finally I was able to get some help from the 511 number. Thus, the entire ticket selling and customer support infrastructure has been reduced to a call centre person, who was possibly working from home.

On 17 June, Amazon announced that it was buying the upscale grocery chain Whole Foods, which suddenly makes it one of the top five grocers in the country. Pointedly, Amazon has been experimenting with no-checkout stores (you walk in, pick up your stuff, and some scanning computer totes up your purchases and charges your credit card). No cashiers, no help. The New York Times even wrote an article echoing my sentiments expressed here, saying that “Amazon’s Move Signals the End of the Line for Many Cashiers”, so I guess the worry is now mainstream.

I have an Indian-origin acquaintance who is a truck driver, hauling containers long-distance across America. He is also seriously worried about his future: there are about 3.5 million truckers in the US who make a decent wage, and their lifestyle will soon come to an end if, as anticipated, self-driving trucks arrive in numbers sooner than self-driving cars go. The Financial Times titled its report “Out Of Road: Driverless Vehicles Are Replacing The Trucker”.

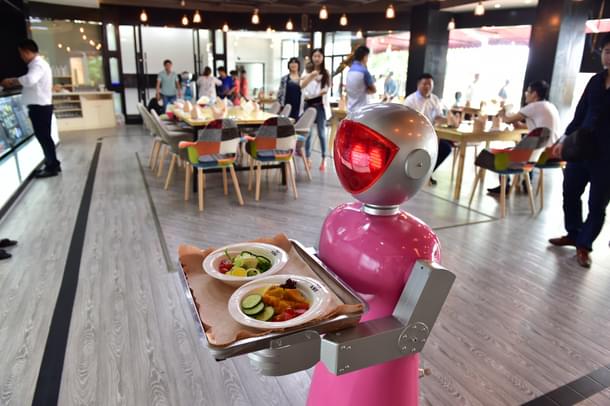

This is on the services front, which was supposed to take up the slack from the loss of manufacturing jobs. And things are only likely to get worse: the most in-demand jobs these days are “data scientists”, “robotics process automation engineers” and “machine learning experts”.

The first means that algorithms will increasingly make decisions about all sorts of areas that middle managers previously used human intuition and experience for. The second means that entire white-collar occupations with relatively straightforward logic and processing will be automated out of existence: for instance, insurance claims processing, paralegal activities such as searching for precedent, paramedical activities such as arriving at preliminary diagnostics. A recent article in The Economist titled “Machine-learning Promises To Shake Up Large Swathes Of Finance” suggests that even lucrative jobs in investment banking are being encroached upon by artificial intelligence, as the third job title indicates.

What Americans may be counting on is that their creative and innovative industries, such as entertainment (Hollywood and TV) and high-technology (Silicon Valley) still hold a big lead over others, partly because of network and cluster effects, as well as the general quality of life and the chance for a big payoff. It is true that American cities are a magnet for the talented from elsewhere in the world, but tightening immigration rules may put a spoke in that particular wheel.

Besides, it may well be that the soft power era where American English has dominated entertainment and culture has peaked. Other languages and industries are coming on strongly: for instance, I noticed that in Charles de Gaulle airport, a lot of the signage is in French, English and Chinese. There is the growth, for instance of Korean K-pop. Anyway, the days when American cultural exports were supreme may be coming to an end, along with the supremacy of the dollar.

The question then is whether all these people thus displaced will ever find meaningful employment. Re-purposing people for entirely new occupations is never easy. The same problem will sooner or later hit us in India as well. In fact, the entire idea of India’s future development has been questioned because it is suggested that the normal route—of moving up the manufacturing value chain—is not available any more, and will get worse with 3-D printing’s rise.

There have been predictions, for instance, that the IT services industry— which, ironically enough, has contributed quite a bit to the loss of jobs in the West—will be badly hit by technological change, especially cloud computing.

A recent report in Forbes is a little more optimistic: “Outlook For Indian IT Outsourcers Not So Bleak After All” suggests that their obituary may have been written a little too soon. It implies that the hardest-bit will be “older” IT workers who would find it hard to retrain themselves in new technologies. It defines “older” as those in their mid-30s!

There are some truly apocalyptic visions floating around. Yuval Noah Harari of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, suggests that “bioengineering coupled with the rise of AI may result in the separation of humankind into a small class of superhumans, and a massive underclass of ‘useless’ people. The 21st century could be looking at creating a world with much greater inequity than anything seen before in human history.” That may alarm rich Westerners, but we, the formerly colonised, have experienced this before. We’ve seen that movie.

Taking a more optimistic view, The Economist suggests in “What History Says About Inequality And Technology” that there have always been gaps between the earnings of skilled people (“artisans”) and unskilled people (“labourers”). They repose faith in the market, and suggest that “as the wage premium for a particular group of workers rises, firms will have a greater incentive to replace them”.

The speed with which the idea of a Universal Basic Income is gaining adherents in the West should be a giveaway: a lot of jobs are simply not coming back, and there will be those who are permanently unemployable. This suggests a particularly grim prognosis for India with its millions of new entrants entering the job market: the Demographic Dividend is this close to becoming a Demographic Disaster unless new ways to employ these people can be found, and soon. Traditional make-work schemes are unlikely to suffice.

Fortunately, this is where innovation can come into the picture. Entirely new industries and businesses may be invented—may have to be invented—to absorb these people.

Maybe it will be in the creative industries: for instance, now there will be a whole lot of Baahubali clone films coming out. And indeed, cinema has been a big employer, overcoming the arrival of computer animation. India has a vast creative tradition in design, (think kolams, motifs like paisley, Kanchipuram saris) and that may well be one answer. Italians, for instance, have exploited their craftsmanship to design attractive cars; Apple has made industrial design sexy. I have long felt that “Make in India” is really “Design in India”, in everything from cars to computer chips to frugal products destined to cause “reverse innovation”, i.e. those that migrate well to developed countries.

These are, not coincidentally, related to areas in which computers are unlikely to ever match or defeat humans: such as aesthetics, creativity, and ethics. There will probably, then, be jobs in the future for artists, dancers, fiction writers, musicians, stand-up comedians, philosophers. Maybe it really is time to get your child off the STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) bandwagon and into the fine arts (though probably not the so-called social sciences!).

Rajeev Srinivasan focuses on strategy and innovation, which he worked on at Bell Labs and in Silicon Valley. He has taught innovation at several IIMs. An IIT Madras and Stanford Business School grad, he has also been a conservative columnist for twenty years.