Magazine

Map Money To Trap Corruption

Prithwis Mukerjee

Apr 17, 2015, 11:56 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 09:08 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

There is an easy solution, coupling available technology with the RTI Act, to track and crack down on government fund leakages

In the chequered history of parliamentary legislation in India, the RTI Act stands out as a significant milestone that puts activities of the government under public scrutiny. But even though the Act gives a legitimate platform for citizens to ask questions on, the process is cumbersome and answers are often given in a manner that is not easy to understand or make use of.

But why must a citizen have to ask for something that is his by birthright? Why can the information not be released automatically? But then who decides what information is to be released? At what level of detail? At what frequency?

The biggest challenge facing India is corruption. It is the mother of all problems because it leads to and exacerbates all other problems. If controlled, the money saved can be used to address most deficiencies in health, education and other social sectors.

Misguided people wrongly believe that having a strong Lokpal will solve the problem, but when bodies as powerful as the CBI and the CVC have been subverted and compromised by political interests, it is foolish to expect one more publicly funded body, like the Lokpal, to be any better. Instead, let us explore how a crowd-sourced and data-driven approach can help track and crack the problem.

Between them, the central and state governments in India spend about Rs 25 lakh crore every year. Even if, very optimistically, only 10 per cent of this is lost in corruption, then the presumptive loss to the public exchequer is Rs 2.5 lakh crore every year.

Look at this in the light of the one-time loss of Rs 1.8 lakh crore in the CoalGate scam.

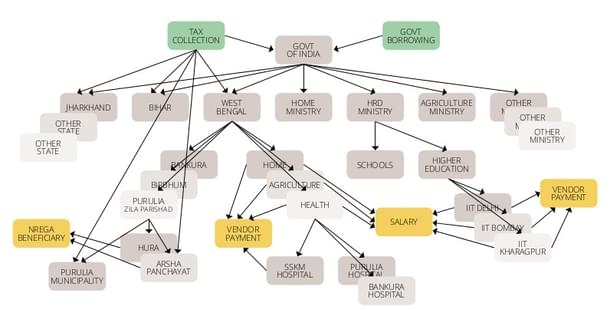

Can we follow the clear stream of public money as it slowly gets lost in the dreary desert sands of government corruption? Most public money starts flowing from the commanding heights of the central government and passes through a complex hierarchy of state and central government departments, municipalities, zila parishads and panchayats until it reaches the intended beneficiary, be it a citizen, an employee or a contractor. Flows also begin from money collected as local taxes and routed through similar channels. The diagram below gives a rough idea of this process.

In the language of mathematics, this is a graph consisting of a collection of nodes connected to each other through directed edges. Each node represents a government agency or public body and each directed edge a flow of money. Inward pointing edges indicate that the node or agency receives money while those pointing outwards represent payments made.

Green nodes are sources where money enters—this could be tax, government borrowings or even the RBI printing notes, while yellow ones are end-use destinations of public money—salaries, contractor payments, interest payments and direct benefits transferred to citizens.

Ideally, the flow of money through this network should be such that over a period of time the total amount that flows into the network at all green nodes should equal the total that flows out into all yellow ones. In reality, the sum will never add up because there is significant leakage, or theft, within the network. The money lost in transit between green and yellow nodes is one quantifiable measure of corruption. Another, less obvious case is the inexplicable or unusually high flows of money—as in the Chaibasa Treasury case at the height of the Bihar fodder scam or for a sudden spurt of expenditure in widening all roads inside a particular IIT campus. Any deviation from norms, either historical or from similar expenditure elsewhere, needs an investigation and explanation.

Can such anomalies and deviations be detected? And how does the RTI Act fit into this picture?

This graph is large, the number of nodes and edges is very high and the problem seems insurmountable. But we can divide and conquer the problem because many tasks can be done in parallel by independent groups. Instead of focusing on the entire graph at one go, we can zoom in on certain segments of the graph and examine specific nodes at higher magnification or smaller granularity. In principle, if the flow through every node is accounted for, then the flow through whole graph gets accounted for automatically.

How do we conquer each node?

Since each node is a government organisation, it falls under the RTI Act and we can demand details of all its cash flows. Once this is in the public domain, it can be examined by private volunteer investigators either manually or through automated software specifically designed for forensic audit.

This piece appears in the April 2015 issue of our magazine. Subscribe now to receive your copy.

In fact, if Google search bots, or software robots, can crawl through the entire web to track down, rate and index trillions of unstructured web pages, it would not be difficult to build software that can track down and reconcile each and every cash flow transaction in India provided the data is publicly available in a digital format.

The results of such investigations and the unbalanced flows that are revealed should also be in the public domain and would be the starting point of either a formal CAG-directed audit or citizen activism directed at the agency concerned. If the cash flows of a particular panchayat or a government agency do not add up or seem suspicious, affected parties should take this up locally either through their elected representatives or through more specific and focused RTI requests.

This may seem complicated but is not really so. All that one is saying is that bodies that deal with public money should publish their financial accounts in the public domain in a standardised format. Obviously, the accounting format for listed companies may not be appropriate since assets and liabilities are accounted for differently and there is no question of profit or loss for public bodies. Instead, the focus is on the cash flow statement. Specifically, how much money is coming in? And where is it going?

How will this work in practice?

First, the CAG and the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India will create a format to report all cash flows in public bodies in terms of a nationally consistent set of cost codes and charge accounts. Next, the CIC will mandate that all public bodies must upload this information every quarter into a public website maintained by the CIC.

As this information accumulates online, volunteer auditors, public activists, anti-corruption campaigners and even the CAG itself, if it wants to, can collaboratively build a website, like wikipedia or wikimapia, that pulls data from the underlying CIC website and displays the cash flow graph. Even as the graph gets built, people can start looking for missing or unusual flows.

So there is no persistent workload on either the CAG or the CIC. However, each public body must prepare its cash flow statement and put it on the CIC website. In any case, a public body is expected to keep a record of all cash flows—through cash, cheque or EFT. This needs to be put into CAG designated format and uploaded periodically to the CIC website.

In fact the CIC website should already be ready, because in October 2014, the DoPT announced that henceforth all replies under the RTI Act will be uploaded to the web in any case!

In the initial stages, the graph will have major discrepancies in cash flow and this could be because all agencies, or nodes, have not been identified or are not reporting information. At this point, activists can put in specific RTI requests to the concerned agencies to report their information in the CAG format and the CIC must ensure immediate compliance. Over time and with a number of iterations, the cash flows through all parts of the network should first become visible and then balance out. Compliance will be achieved by continuous RTI pressure at the grassroots, applied in a parallel and distributed manner, on defaulting government agencies.

When known outflows do not match inflows or if there are deviations from expected norms, activists can draw the attention of the media and opposition politicians who can raise a hue and cry. This should lead to the usual process of investigation where the CVC, the CBI or even the Supreme Court can get involved.

After all, Al Capone, the notorious Prohibition-era US gangster was finally convicted on the basis of a forensic audit, not a shoot-out police operation!

Unlike the top-down Lokpal-driven approach, this bottom-up strategy calls for no new law, no new agency, no new technology, no new infrastructure. All it needs is a format to be defined by the CAG and for the CIC to ensure that any RTI demand in this format be addressed immediately.

With this, the flow of public money will become visible. If this transparency leads to a reduction of only 10 per cent of the presumptive loss of Rs 2.5 lakh crore, it would still mean an additional Rs 25,000 crore for the Indian public every year, certainly not a small amount.

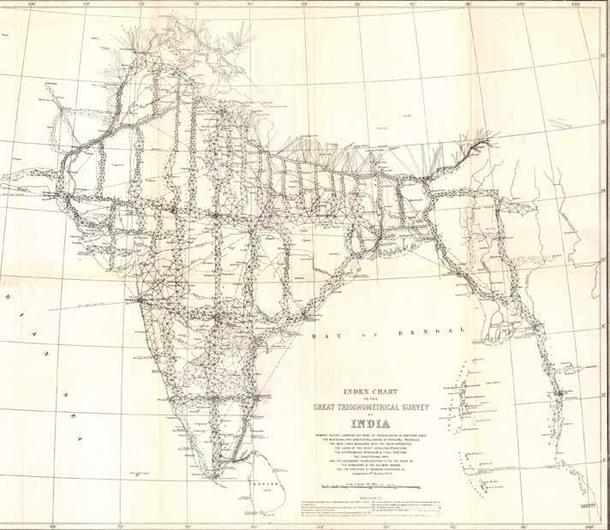

Nineteenth century British India had the vision, the audacity and the tenacity to carry out the Great Trigonometrical Survey that created the first comprehensive map ( see diagram) necessary to govern this vast country. Armed with the digital technology of the 21st century, a similar mapping of all public cash flows will lead to greater transparency in the governance of modern India.

Prithwis Mukerjee is an engineer by education, a teacher by profession, a programmer by passion and an imagineer by intention. He has recently published an Indic themed science fiction novel, Chronotantra.