Magazine

The Art of Questioning

Sanjoy Mukherjee

May 08, 2015, 11:00 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 09:28 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Why do the same doubts and questions come back to us, time and again? Why can’t we resolve our material issues and rise to a higher level of consciousness? The Prasnopanishad may have some answers.

My journey with Ethics and Values began in April 1993 at the Management Centre for Human Values, IIM Calcutta. Seasoned corporate executives or even MBA students would often raise these typical questions during our work shops and management development programmes.

“We are deliberating on ethics and values. But the business world at large resorts to unethical means for short-term gains. Are we not discussing all this in a utopia?” “The people who struggle to remain good suffer in life in material terms. Why then should we be scrupulously honest in our professional dealings and get a rough deal in life?” “When most of your colleagues are cutting corners for business gains, why should not I join the bandwagon and get access to good things in life?” “When the boss demands results at any cost, how can I opt out of the rat race for targets and profits?” “This is a cruel world where no one offers a free lunch. Talks on ethics and values are fine for classroom but how can it be relevant in today’s world?”

The list could go on.

What I found intriguing was not the purpose behind asking these questions. Such questions come naturally to the mind of someone who is sensitive to issues of ethics but also aware of harsh reality.

Yet they want to perform well at work and also want a good life for themselves and their family.

The problem was somewhere else.

And that was what bothered me the most.

The training programmes would often end with the participants coming to a near-consensus on the importance of following a value-based life, both personal and professional. This would be evident from the feedback, both formal and informal. They would also be vocal about taking this up as a top priority item in the days to come. But the days to come would reveal something else.

Many of the organizations wanted us to conduct Reinforcement Workshops on the same topic after six months or one year with the same pool of participants. We would conduct the programmes with some new perspectives and practices. The participants would engage in lively intellectual conversations during these days and share their experiences. But at the end of it all, they would go back to square one.

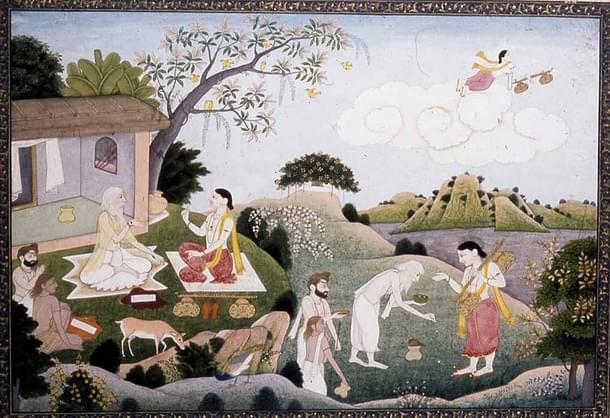

“But sir …” The same questions. Something must be going wrong somewhere, otherwise why should this happen? I was groping for an answer. Then I discovered the Prasnopanishad—an entire Upanishad dedicated to the art and science of asking questions and delivering the right answers. It begins with a quest—both individual and collective. Six young men burning with the desire of receiving knowledge of Truth leave home and set out from their homes. They belong to different families, each with its unique lineage. They all happen to converge in the woods in search of their answers. Finally they happen to arrive at the hermitage of a sage (rishi).

What follows is amazing. When they meet the sage, there is no conversation on their quest. The sage welcomes them and asks them to stay with him at the hermitage. They will have to first get attuned to the ambience. In ancient India, the space for dissemination of knowledge was not the city state as in Greece or Rome but in forests where the human being would live in intimate contact and communion with Nature. Tapovans— ”van” meaning forest and “tapas” meaning the intense seeking of Truth and the pursuit of a lifestyle to acquire the same.

In the heart of the forest begins the process of mutual observation. The young men must first observe the sage in all his daily chores and dealings to decide whether they have come to the right person. The Teacher on his part will ob- serve the seekers and evaluate whether they are sincere in their quest and firm in their resolve. The transmission may begin months after their arrival in the hermitage.

The sharing of knowledge begins with asking questions. The Upanishad unfolds a sequence. It begins with the first seeker asking a question from the material plane of existence. Before he raises the question, the Upanishad gives details about the background of the young man—his family, place of domicile, lineage. The question is not treated as a random query. It is seen as having a direct connection with the questioner’s background.

The sage then enters the picture. During his discourse, he unfolds all the possible dimensions of the material plane of the problem. Each issue at that level is discussed threadbare, leaving no space uncovered. At the end of the discourse, the sage ensures that there is no further doubt or question hanging loose or hidden in the minds of all the six seekers. Then the conversation moves ahead.

All doubts in the material plane having got resolved, the sage welcomes the question from the second seeker. This question pertains to the vital plane of existence—prana. What is interesting here is that there is no further reference to the material plane in this round. The entire conversation now revolves around the vital being; no question springs back from the former (material) domain as it has been fully and comprehensively handled and answered before.

The dialogue then moves on to the next levels of existence, each articulated specifically by the other four seekers.

And the conversation takes us to the next levels of consciousness—mental, supra-mental and finally spiritual and transcendental. In more recent times, Sri Aurobindo in his magnum opus Savitri and more specifically in The Human Cycle had identified these distinct and unique layers of human existence and consciousness—physical or material, vital, mental, supra-mental and spiritual. What is pertinent for us in the learning situation is that there is a gradual evolution of human consciousness from one level to the next one.

Unless we have understood the multiple dimensions of existence at one level of consciousness, we cannot have proper access or perception of the next level in the order of ascent. It may also be noted that all the seekers in the Prasnopanishad ask questions related to the ascending levels of consciousness. They never fall back on doubts related to the earlier levels as they have been resolved completely. The question may have been raised by one seeker, but by virtue of his competence, the sage has transported all six seekers to higher levels of consciousness in a collective voyage so that there is no hangover from the previous layers in the minds of any one of them.

In the words of Sri Aurobindo, this is the path of ascent of human consciousness from the material to spiritual plane along the Human Cycle of Evolution.

At the end of the conversation in the Prasnopanishad, there is an ascent of the consciousness of the seekers, both individually and collectively. They are all elevated step by step to a new life, a new dawn, where clarity and depth of Truth dispel the mist of confusions and doubts.

I look back and ponder in wonder.

What did we achieve then in our courses and training programmes, when we received such glowing feedbacks? Maybe just some intellectual stimulation but no real transformation of the participants’ mindset or consciousness. I always had this problem about changing of mindset that I may discuss some other time. But where is the expansion of mindspace? Or ascent of consciousness?

Otherwise, why will the questions come back time and again, even after long years?

The author is a Faculty of Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility at IIM Shillong. He has been invited to speak at several prestigious forums—the Aspen Institute, the Oxford Roundtable, the Global Ethics Forum (Geneva), and International Wisdom Conference at CEIBS, Shanghai, among many others. At IIM Shillong, he is the Chairperson of the Annual International Conference on Sustainability.

Sanjoy Mukherjee teaches Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility at IIM Shillong.