Magazine

The Musical Genius That Was Maharajah Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar

Ratna Rajaiah

Oct 01, 2019, 05:05 PM | Updated Oct 02, 2019, 11:49 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

“He could have composed a concerto in raga Darbari but he didn’t.” so says Dr Deepti Navaratna, former Harvard Medical School neuroscientist, now musician, regional director of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and one deeply, madly in love with the Maharajah Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s music.

Chandrayaan-2 may not have happened if a 21-year old, freshly-crowned 25th Maharajah of Mysore, Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar, had not been fired up by the idea of an industrialist, Walchand Hirachand, to set up India’s first aircraft manufacturing company.

Which is how Hindustan Aircraft was born on 23 December 1940. Sixty-nine years later, the company, now called Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), manufactured the orbiter’s structure for Chandrayaan-2.

And just a couple of years later, in 1942, ten years before it was even a thought in Jawaharal Nehru’s head, this young king conceived of India’s first ‘Five-Year Plan’ that would reach out to every tiny taluk and village in his kingdom, covering every possible area with good governance.

Providing drinking water, roads, schools, libraries, centres for improvement of farming and animal husbandry practices, even veterinary hospitals. Health care, where there was a special focus on women, providing a wide range of maternity care facilities, including maternity leave for female labourers and government employees.

And agricultural research. In “Sakkare Nadu” (sugarcane country), as Mandya is known because it is a prime sugarcane region, a laboratory to research the prevention and treatment of sugarcane pests came into being in 1946, the very first of its kind in India.

Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar gifted the magnificent Cheluvamba Mansion in Mysore (originally built by Maharajah Krishnaraja Wadiyar for his sister, Cheluvajammanni) to the Indian government to start the Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI).

And because he thought that “man cannot live by bread alone”, Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar also sponsored the first comprehensive translation of ancient Hindu scriptures from Sanskrit into Kannada as part of the Jayachamaraja Grantha Ratna Mala, which included 35 parts of the Rigveda.

And because of his government’s patronage of a little (India’s first), 6-year old and till-then privately run radio station, on 1 January 1942, India’s first Akashvani was born. The name caught the imagination of the country and became the synonym for the national broadcaster, All India Radio.

His unflagging patronage of arts and culture earned him the title “Dakshina Bhoja”, after the 11th century Raja Bhoja of the Paramara dynasty, famed for similar proclivity.

The list is long.

But hey, this is stuff that rajahs do.

Not all rajahs, in fact not many rajahs but the great maharajahs who light up the annals of history.

And Jaya Chamraja Wadiyar had one of the greatest teachers in kingship: his doddappa (father’s elder brother) or uncle, Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, whose reign was so progressive that he was called Rajyarishi and Mahatma Gandhi dubbed the Mysore kingdom as ‘Ramrajya”.

In fact, Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s 5-year plan and much of his administrative excellence was his effort to carry forward what his uncle had already initiated. It was a very massive and tough act to follow, which he did with great success.

So the question is: how many such kings have also found time to become one of the greatest Carnatic music composers, that too one that was so proficient in Western classical music that he almost became a concert pianist?

The answer goes back to the richly fertile nursery in which the young Prince Bahadur’s musical genius took root and blossomed.

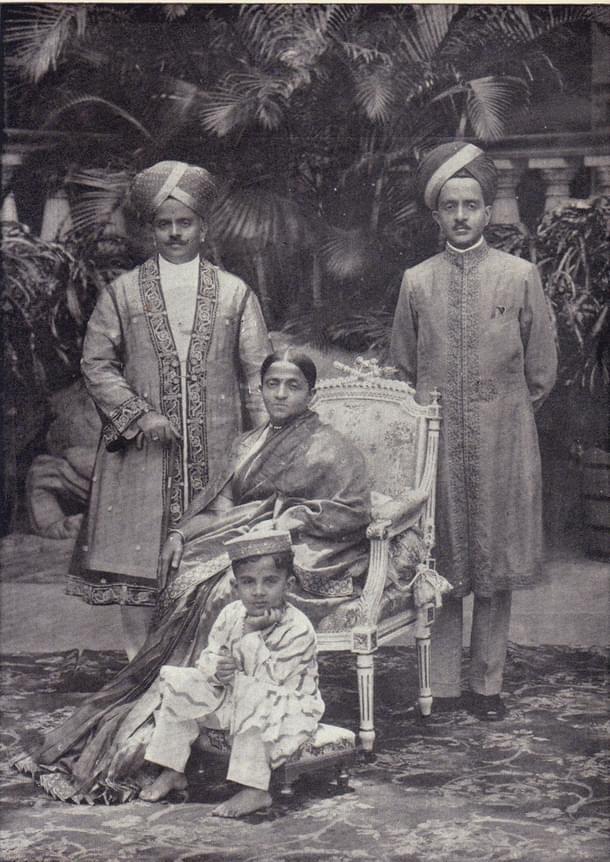

His first piano teacher was his mother, Kempu Cheluvaja Ammanni Avaru. His father, the Yuvaraja Kanteerava Narasimharaja Wadiyar, was a jazz aficionado and Chamundi Vihar Palace, (where Jaya Chamraja Wadiyar spent his childhood, now a sports stadium) was frequented by the likes of the violin child-prodigy-maestro, Philomena Thumboo Chetty.

In the main palace, decades before “fusion music” became fashionable, his uncle, the Maharajah Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, actively encouraged cross-pollination between Carnatic, Hindustani and Western classical music.

He himself played the flute, the violin, the saxophone and the piano along with four other Indian instruments. Hindustani classical luminaries like Abdul Karim Khan, Gauhar Jan and members of the Agra Gharana were regular performers in his court.

Western musicians permanently took up residence there, and among the glittering galaxy of legendary Carnatic music asthana vidwans, the great vainika, Veena Seshana also played the piano, the bugle and the micro-harp.

And Veena Venkatagiriyappa, who was also one of the directors of the palace band, compiled a collection of Carnatic classical compositions using Western musical notations!

The palace was regularly filled with a most unusual sound — the music of the Royal Carnatic Orchestra that played with a mix of Indian and western instruments (including the xylophone and the trombone, believe it or not!).

And its repertoire — as its name suggests — reflecting its unique potpourri nature, included Carnatic compositions and Hindustani classical music dhuns.

So, by the time he was a young man, Jaya Chamaraja’s knowledge of Western classical music (it is said that his collection of music records was so vast and varied — numbering at 20,000 — that gramophone record companies would often borrow some for reprints!) and his proficiency as a pianist was so good that he decided to visit the great Sergei Rachmaninoff in Switzerland looking to being accepted as a student.

But fate, as it has always had a bad habit of doing, intervened.

In 1940, within six months of each other, both his father and his uncle, the Maharajah Krishnaraja Wadiyar passed away. And so, on 8 September 1940, the would-be piano virtuoso ascended the Mysore Ratna Simhasana and became the Mysore kingdom’s 25th Maharajah.

And he could not have done so at a more difficult time. World War II was a year old, the political scene in India was tumultuous, to say the least, with Mahatma Gandhi striding the Independence movement like a colossus and the birth of the Quit India movement gaining impetus, impatient to be born.

The just-crowned, just-turned-21 Maharajah could already feel the heat of all this while shouldering the responsibility of having to carry forward the huge legacy of his uncle. And the turbulence of the external world was reflected in his 2-year-old marriage, which was on the rocks.

They say that in difficult times, many turn inwards and to their roots. As did this young Maharajah.

The two greatest influences in his life — his mother and maternal grandmother’s elder sister — guided him onto the spiritual path. And so, initiated by his spiritual guru, the great sculptor, Siddalingaswamy, he became an upasaka (follower) of Sri Vidya, a Hindu Tantric religious system devoted to the Devi, in which she is worshiped in the form of a mystical diagram (yantra) called the Sri Chakra.

Perhaps this egged the until-now dormant cross-pollination of musical influences of his childhood to emerge, and he turned to Carnatic music. His formal training was from two asthana vidwans — Mysore Vasudevachar and Veena Venkatagiriyappa.

But it was the coming together of his own virtuosity in Western classical music as a pianist, the influence of Muthuswamy Dikshitar (who was also a Sri Vidya upasaka) and his inward spiritual journey towards the Devi that was responsible for what emerged...no, let me rephrase — that was responsible for what burst forth as a stupendous, incandescent lava of musical brilliance.

Ninety-seven kritis or compositions (94, until three more were released this year by his family on the occasion of his birth centenary). And some say — perhaps hope — that he may have composed 108, that sacred number! So maybe 11 more will pop up somewhere in the future!

Ninety-four of the 97 compositions were composed in a period of just about 2 years, the very first one on Ganesha (naturally) – Shri Mahaganapathim — on 17 August 1945. In the following 12 months, he composed about 30 kirtis and by the end of 1947, the balance 64.

Wait. You need to garner more breath because you will gasp harder.

Not a single one of these kritis are repeated in the same raga. I will be bold enough to say that no one has done this before, not even the great Trinity of Carnatic music. It also meant that he had not just knowledge of 97 ragas but knowledge deep and thorough enough to compose in them.

And many of these are rare ragas, with just a few compositions in them.

Like raga Hatakambari in which he composed Hatakeswaram bhajeham, a kriti to one of Lord Shiva’s lesser-known avatars — Lord Hatakeshwara.

Raga Nilaveni, in which he composed Balakrishnam bhavayeham, one of the just 4 kritis that he dedicated to Lord Vishnu.

Raga Shivkhambhoji in which he composed Kamakshi paahimaam, inspired by Adi Shankarachrya’s Tripurasundari Ashtakam.

Raga Kamavardhani in which he composed Kamesvarım Kamavardhini, in which he refers to the 64 arts or chatushasti kala. It is said that only a very few have become proficient in all 64.

Like Sri Krishna and Balarama, who learnt them from sage Sandipani. But the Devi is considered the most proficient — “chatushashti kalatranga yoginim”, as he describes her.

Then there is Suvarnangi, Vishvambari ,Shadvidhamargini, Rishabhapriya, Kokilapriya, Gambhiranata, Kokilabhashasni, Malavi, Vagadhishwari, Pratapavarali, Hamsavinodini, Nagadhwani, Nadabrahma.....

Stop, you plead and demand — how many? Well, depending on which expert you talk to, the total number of such ragas used in the Jayachamraja Wadiyar treasury varies anywhere from 15 to 40. Let’s just say the number is ‘gasp-worthy’!

They also include eka kriti ragas. For example, raga Durvangi in which he composed Gam Ganapate Namaste. Eka means one and therefore these are ragas in which only one kriti has ever been composed.

Then there is also raga Bhogavasantham — the discovery of this raga is credited to Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar and if, as it is claimed, his composition Amba Rajarajeshwari is the only composition in it, it makes one more eka-kriti-raga in his kitty.

And according to Dr T S Satyvathi, the well-known, award-winning musicologist, out of the 94 compositions, 38 are eka-kriti-ragas!

Which brings us to a tricky bit.

Do and can Carnatic music composers create new ragas? Some experts say absolutely not while others say absolutely yes.

So, if we were to go with the yays, according to his devoted chronicler and son-in-law, R. Raja Chandra (whose book Sri Vidya Ganavaridhi, released in 2010, is the first comprehensive compilation of his father-in-law’s compositions), Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar created just one - raga Jayasamvardini.

According to Dr. Deepti Navaratna, the number of new ragas that he created ragas is 30. Which makes it time NOT to ask the question: why are his compositions so little known, heard and sung?

(Even though, of the five compositions — not counting the opening English song by C Rajagopalachari — that M S Subbulakshmi sang at that historic concert at the United Nations in 1966, along with Muthuswamy Dikshitar’s Rangapura Vihara — Maharajah Swathi Thirunal’s Sarasaksha Paripalaya, Vadavarayai Mathakki from the Tamil epic Silappadhikaram and Maithreem Bhajata, a benediction by Jagadguru Shri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati that was set to music by — yes, believe it or not — Vasant Desai, she also chose to sing Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s Shiv Shiv Bho.)

That’s because I have already mentioned a small part of the answer in the previous paragraph. This is the breathtaking (and therefore daunting) musical expanse of Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s work, which traverses from the most popular to the rarest, little known, unknown, even freshly composed ragas and talas.

Some of the rare talas he has used are: Khanda triputa, Mishra jhampe, Trishra jhampe, Chaturasra madhyam, Chaturashra dhruvam, Khanda rupakam and Mishra triputa. This necessitates not a little amount of musical erudition, making many of his compositions beyond the scope of many except scholar-musicians.

But more importantly, as Dr Satyvathi says, his kritis are musically complex, requiring mastery of voice modulation and voice culture. Both she and Dr. Deepti Navaratna point out that they are the result of the mind of a pianist at work.

And as Dr. Deepti explains, while both Hindustani and Carnatic classical music are linear in nature — one swara following the other — the genius of Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar is that he used Western harmonic vocabulary (chords) and translated them into Carnatic compositions.

Which is why, even when classical-music-illiterates like me listen to them, we are astounded by the sudden flashes of what sounds like Western classical music! In fact, it is said that he often composed his kritis on the piano, of which he had several, though not 97, one for each kriti, could we say?

Then they are all in Sanskrit, which demands not just knowledge of this language but again, as Dr. Satyavathi points out, also mastery over pronunciation and articulation; and since the sahitya (lyrics) is dense, close-knit, with little room for breath, it demands excellent breath control.

Add to this the fact that the Maharajah’s vast scholarship in ancient scriptures and texts like the Vedas and the Upanishad are encrypted into his compositions. So, in order to do justice to the sahitya, one would have to have knowledge of these references.

For example, Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s depth of knowledge of various aspects of Shaktism including yogic practices like Kundalini yoga (in his review of British Orientalist John Woodroffe’s book “Serpent Power” in The Hindu, he called it ‘the most important of Shakti tantras’) and the importance he gave to yoga reflects in the repeated references to it in his kritis.

So, as Raja Chandra points out, he often calls himself ‘Raja Yogindra vandita’ in them. And in his composition, Sri Chamundeshwarim bhajeham (raga Madhyamavati) he describes the Devi as ‘Kundalinim manonmaneem yogidhyana gamyam navaksharatmikam’ and the kriti ends with him signing off as ‘Raja Yogindra vandita kuladevim’.

And Lambodhara pahimam in raga Narayana gaula, refers to the story of how Ravana, through his tapasya, persuaded Shiva to part with the Atma Linga for his mother (also an ardent Shiva devotee) and how Ganesha, roped in and aided by Vishnu, tricked it out of Ravana’s hands – literally!

The final icing on this already difficult cake is the overriding influence of Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar, the Sri Vidya upsaka (in every kriti, his sobriquet is “Sri Vidya”). According to Dr Deepti, this made the sahitya of the kritis very profound, often cryptic, loaded with mystical imagery and difficult to understand.

And of the 94-plus compositions, 67 are on the Devi in all her avatars.

Which leaves me to tackle the whispered allegation (some not-so-whispered, like R K Narayan’s, who made it in an interview to the Frontline magazine) that Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s kritis were ghost-composed; most probably by Mysore Vasudevachar.

I have two rejoinders to it. One by Dr Satyvathi, who pooh-poohs it away, saying that it is almost mandatory to accuse all royal composers of this, including Maharajah Swati Tirunal and Someshwara Chalukya.

But the second more-befitting and beautiful one comes from his son-in-law, Raja Chandra who says that the Maharajah never composed with a view to public consumption. It was just the result of the deepest desire of an ardent devotee to have something to offer to his beloved Devi during his puja.

Sigh.

There is a sadness washing over me as I write this. Because what made Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar one of the greatest composers of Carnatic music in modern times also shoved him into the rarefied, distant, faintly-heard echelons of scholar-musicians and most probably, he will always stay there.

And also because, the princely state of Mysore, once a “Ramrajya” because of the magnificent and progressive governance of its Wadiyar kings, is now in present-day Karnataka, where politicians plunder both its people’s and its land’s wealth; where it is maamooli to scam and horse-trade and conduct resort-to-resort politics, only when you are not pretending to govern while holed up in a 8-star hotel facility costing upwards of Rs 2 lakh a day.

Sigh.

But it is Dussehra, always a season of hope, when Ravana turns to bhasma and when Mahishasuramardini beheads the buffalo demon Mahishasura. And it is the season when, at least in Mysore, the air is filled with the magical sound of Jaya Chamaraja’s music.

So, I end, if not on an upbeat note, then certainly on a beautiful musical one. I first heard it sung exquisitely by Dr Deepti Navaratna, one of Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar’s most ardent fans, who has also set it to music.

Normally, the shishya writes a eulogy to his/her guru. But in this case, it was the guru, none other than the great Mysore Vasudevachar who wrote this tribute to his shishya — Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar!

I wish you would hear Dr Deepti sing it, her lovely voice swirling and soaring up like agarbatti smoke up to the heavens, in a ragamalika of the ragas Vasanthi, Mohana and Bhooplam.

But even just the sahitya itself is enough.

Nirupama chakradheeshwara karuna poornam sudhimanistutyam

Jaya Chamaraja bhoopam rakshasu satatam krpanidhihi krishnaha

Shri madyadukula varidhi rakchandram sushila gunasandram

Jaya Chamarajavaryam kripaya suciram shriyaha patihi payat

Monarch with no equal, embodiment of compassion, celebrated by the wise.

Oh Krishna! You, who are the treasure of grace, protect and guide Jaya Chamaraja, the mighty king

Oh, torchbearer of the Yadukula clan, iridescent as the moon, scrupulous and virtuous.

May the revered Jayachamaraja be blessed with prosperity for a long time to come!

This article would not have been possible without 3 people whom I mention with heartfelt thanks:

Dr T S Satyavathi, renowned musician and scholar, who at the age of two years, sang before the Maharani of Mysore.

Dr Deepti Navaratna, musician, musicologist and regional Director of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

R Raja Chandra, son-in-law and chronicler of Maharajah Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar.

Photos : courtesy R Raja Chandra.

-- Ratna Rajaiah is an author and a columnist. She lives and cooks in Mysore.