Magazine

What It Means To Grow Poor And Female In Saudi Arabia

Bhavdeep Kang

Sep 05, 2017, 07:35 PM | Updated 02:37 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

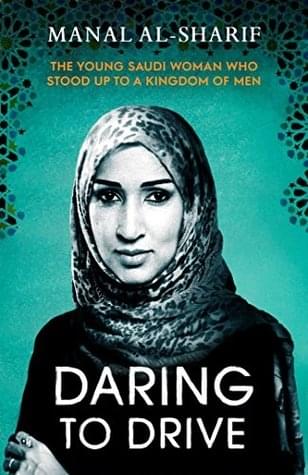

A RIVETING AND often blood-curdling read, Daring to Drive is a visceral account of what it means to grow up poor and female in Saudi Arabia, at the bottom of the social hierarchy and vulnerable to the worst excesses of the patriarchy. In that sense, it is a departure from the genre of Jean Sasson (The Princess Trilogy) and others, who offered a glimpse into the cloistered lives of Arab women of privilege — although both vividly depict the savage repression of women in the name of Islam.

Manal Al-Sharif’s story is bluntly told, straight from the shoulder, with no literary flourishes. Her stylistic simplicity counterpoints the complexity of the socio-religious edifice in which Saudi women are trapped.

Sasson introduced the world to the gilded ghetto behind the black curtain of the zenana. Her heroines, wrapped in Dior and reeking of Chanel, had access to the power structure and a measure of immunity from the mutawas or religious police. Al-Sharif has no such protection. Her public defiance of custom draws the full wrath of the radicalised state down upon her head and only the intervention of the king can rescue her.

‘Daring to Drive’ just might be the most important book of its kind since Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.

Mobility is the underlying theme of the book. Saudi Arabia’s ban on women drivers restricts their freedom of movement, in much the same spirit as foot-binding in medieval China. Cabined, cribbed and confined, women are literally and figuratively denied scope for advancement. The young girl’s urge for self-development runs counter to the immobilising pressure of convention, creating a palpable tension throughout the book.

Even as she documents the horrors — disguised as rites of passage — that every Saudi girl must undergo, the narrative never degenerates into a rant. Al-Sharif’s empathy extends to her oppressors, as she offers penetrating insights into the society which created them. Nowhere is this more evident than in her relationship with her parents, who collaborate in her circumcision, but stand by her when she is jailed for dissent. She carries the scars of her mother’s cruel beatings, but acknowledges her fierce commitment to educating her daughters.

Visibility is a parallel theme. The desire to be seen as an individual, distinct from the faceless mass shrouded in black. Even when she embraces Salafi radicalism and retires behind the niqab, she is exercising a personal choice. Brainwashed into accepting the patriarchy’s version of the faith, she rejoices in (but later regrets) the fact that it sets her apart from the rest of her family.

The reader is introduced to the best and worst of the Saudi male through the three men who, in law, have absolute control over her person. Her brother, the closet feminist. Her husband, the male supremacist. And her father, whose brutal chauvinism wars with his paternal instincts. He is unsparing with the rod throughout her formative years, as are all her authority figures.

Yet, he is her chief enabler, driving her to college and back so that she can get an education and a job.

Her childhood is set in the slums of Mecca. Bit by painful bit, she internalises what society expects of her and begins to understand the inherent contradictions.

A society that “frowns on a woman going out with a man; that forces you to use separate entrances for universities, banks, restaurants and mosques; that divides restaurants with partitions so that unrelated males and females cannot sit together; that same society expects you to get in a car with a man who is not your relative, with a man who is a complete stranger, by yourself and him take you somewhere inside a locked car, alone”.

It is a society which permits women to die rather than breach parameters ostensibly instituted for their protection. Her experience of this dichotomy begins with her birth, on the floor of her family’s small apartment. Her mother is alone, because a woman — never mind that she is a mother of five — cannot go to a hospital without her male guardian.

Al-Sharif’s awareness of the asymmetry grows and fuels her resolve to defy the proscription on driving, to be mobile.

Green shoots of empowerment come with financial independence. “Having money enabled me to make decisions and follow them through... Now, for the first time in my life, I had freedom to choose the colour of my clothes and shoes, my hairstyle... These choices, although simple, gave me the feeling that I had some say over my life.”

Liberty is addictive. Al-Sharif abandons the security of home for a job with Aramco and within the confines of its campus, outside the regressive framework of mainstream Saudi society, she discovers the joy of driving.

It is the internet which gives Al-Sharif and her sisters an identity and a voice. Twitter and YouTube offer them a platform for communication, collaboration and organised protest, thereby creating a sisterhood without borders. Her sojourn in the United States firms up her resolve to follow in the footsteps of the 47 brave sisters who, in 1990, drove on the streets of Riyadh (and were arrested).

In 2011, her twitter handle @Women2Drive called on all Saudi women to take to the streets in their cars.

Al-Sharif herself got behind the wheel, with a camera recording her rebellion. The simple act of a woman driving shook the patriarchy to its core. She landed in jail for the crime of “driving while female”. Released eventually, she came to realise that living in Saudi Arabia was no longer tenable for her.

The author leaves us with a haunting question: “There are stories of women who are starved, stabbed, burned, kicked out of their houses and even locked in psychiatric institutions by male family members... When I hear these stories and meet some of these women, I wonder in my heart... what has happened to the two fundamental principles of being a Muslim — living in peace and showing compassion?”