Politics

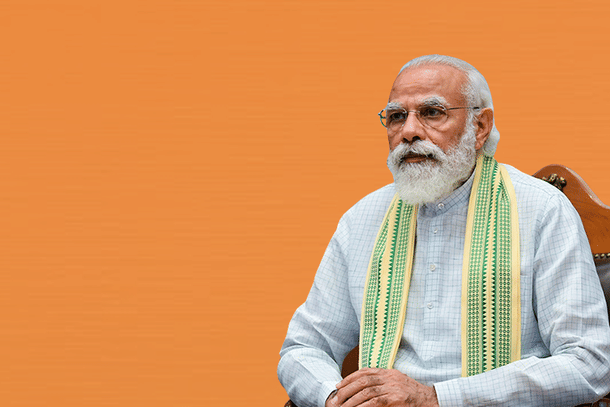

2024 Isn't A Done Deal: To Win, Modi Must First Enthuse His Own Hindu Base

R Jagannathan

May 25, 2023, 10:32 AM | Updated 10:29 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The gradual build-up of opposition unity, which includes a substantial boycott by many parties of the inauguration of the new Parliament building this Sunday (28 May), should begin to worry the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

In many ways, Narendra Modi is in a situation similar to Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2004 — personally popular with the masses, but with the general voter looking for other options.

But more than opposition unity, what Modi should really be concerned about is the disenchantment within his own Hindu-Hindutva base.

While few people associated with the Sangh Parivar are willing to say this openly, the truth is its karyakartas are no longer as enthused as they were about expending a lot of effort to get Modi and his party re-elected.

The message Modi needs to internalise is that he cannot take his own committed voter and karyakartas for granted. An unenthusiastic core voter base is not going to lead Modi to victory in 2024.

The outcome of that general election can no longer be assumed to be headed in a favourable direction for the party.

Where exactly has Modi lost traction with his own party and Sangh base? Hasn’t he ensured the abolition of article 370, enabled the construction of the Ram Mandir after a favourable court verdict, expanded the party base, and brought nationalism to the forefront in his public rhetoric?

What the Sangh karyakarta is miffed about is not the promises that have been delivered, but Modi’s gradual move away from Hindutva issues to something that is closer to the Vajpayee line, even a Hindu version of Jawaharlal Nehru.

Sabka saath, sabka vikas is fine with the average Sanghi, but if sabka vishwas means leaning over backwards to court the minorities, they fear that this is no different from Congress secularism.

Modi has shown no inclination to abandon this anti-Hindu form of secularism, and that is a clear downer for the karyakartas and core Hindu voters.

Secondly, the government has shown no real inclination to take up issues relevant to giving equal rights to Hindus. These issues include freeing temples from state control, rewriting Left-liberal history, amending articles 25-30 of the Constitution that give special rights to minorities, and working out a strategic map for establishing the essential Hindu character of India for the future.

As things stand, if the BJP’s own Lok Sabha seat share falls below 220 in 2024, it could enable a return to the pre-Modi policies of the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). The Hindutva base that was rooting for Modi in 2014 and 2019 is disenchanted with the progress made on the issues dear to it.

This is one reason why the BJP lost Karnataka, and no amount of last-minute references to “Bajrangbali” could change the mind of the fence-sitting Hindu voter.

Third, the “labharati” class, those who benefited from Modi’s pro-poor schemes (Ujjwala, Kisan Samman Nidhi, et al), is sensing that all parties can deliver freebies, since all of it comes from the same public exchequer.

This implies that benefits attributed to Modi’s special concern for the poor are no longer associated with him to the same extent as in 2019.

The karyakartas know that the ground is shifting under the BJP, but they have been given no special importance within the party where they can be committed to bringing the party back to power.

Some of them may not be prepared to go that extra mile for the sake of the party. And those who do are in it because there is no alternative.

This is not to suggest that karyakartas are out of tune with the leadership everywhere.

But they are most aligned in states where the local leadership has shown a greater commitment to Hindutva, as in Yogi Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh, or Himanta Biswa Sarma’s Assam.

Fourth, the BJP should know that no amount of pandering to the minorities will ever bring in a substantial share of their vote, and this includes the Pasmanda Muslims whom the party is trying to woo.

If a single dog-whistle from the Congress about banning the Bajrang Dal could bring in the entire Muslim vote in Karnataka, what exactly is left for the BJP here?

For the karyakarta, the open BJP pandering to minorities is deeply troubling. If Muslims are going to be wooed repeatedly, and they have to do this wooing on behalf of the party, where does this leave their own commitment to Hindutva?

The bottomline for Modi and the BJP is simple: the party needs to be more pro-Hindu not just in rhetoric, but in terms of policies too. The BJP does not have a long-term future if it is not a decidedly Hindu party.

There is no shortage of secular parties for the voter to choose from, but there is a Hindu party missing in action. If that Hindu vote stays silent in 2024, the BJP will lose power.

2024 for Modi is not a done deal; his main challenges are within. He cannot win if his most enthusiastic supporters are sulking in the shadows.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.