Politics

Ayodhya: The Movement Before The Movement

Aravindan Neelakandan

Oct 25, 2023, 10:21 AM | Updated Dec 26, 2023, 05:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Till the 1980s, one would come across 'Ayodhya' only in advertisements related to pilgrimage tours.

That was until the name of the city became national news.

One needs to understand this shift in the focus on Ayodhya itself to truly grasp the nascent movement that was taking shape — the struggle for Shri Rama janmabhoomi.

The Nehruvian state was indifferent at best and repressive at worst, towards the civilisational impulses of India. This resulted in a state divorced from the heartbeat of a nation.

The media and academia followed suit.

Here's an example.

In school, children learn about Ashoka's 'conversion' to Buddhism as one of the earliest 'ethical' moments in Indian history. They are subtly taught that this conversion was positive, ethical, and a step toward rectifying a perceived spiritual deficiency in the older Vedic culture.

However, the historicity of Ashoka's conversion is debated.

Regardless, every Indian child was exposed to this narrative which subtly favours non-Hindu religions over Hinduism.

This tendency to minimise the ethical and spiritual aspects of Hinduism while highlighting other religions is a distinctive feature of independent India's education system.

Same has been the case with politics.

Dravidianists, Marxists and Nehruvians attacked the Hindu religion. Some attacks were crude and obscene. Some were suave. Some unspeakable.

On the other hand, even minor criticism of other religions would not be allowed in public space.

To add to this, the two decades preceding the 1980s, saw regular communal riots in different corners of the country.

Secularists blamed religions generally. Hindus specifically.

Elite artists held art exhibitions. Heart-touching poems, in Urdu, about secular human values would be published in elite literary magazines and communal harmony would be idealised on screens.

But pages of magazines and screens of theatres were the boundaries of this concocted utopia. It had no geography in reality.

Such socio-psychological stress was bound to have consequences.

The Seeds Of A Mass Aovement

It was the year 1984. On 7 and 8 April, thousands of Hindu sadhus and sanyasins had gathered in New Delhi for the Vishwa Hindu Parishad's (VHP) Dharam Sansad.

Here, a resolution was passed that the three structures imposed by ‘Muslim marauders’ after the destruction of the temples at the most holiest of the places for Hindus — Kashi, Mathura and Ayodhya — should be removed and the temples should be rebuilt on the spots.

Out of the three, the first objective was Ayodhya.

The snap election of 1984 delivered a landslide victory for the Congress party with a brutal majority in Parliament.

Amongst other things, it showed that Hindu consolidation at the political level was not entirely impossible.

Come 1985 and the Shah Bano controversy erupted. The government of the day ultimately bent in favour of Islamist appeasement. Even the few parties and individuals who initially took a comparatively progressive stand were quick to backtrack.

So, despite unprecedented political Hindu consolidation behind the Congress, Islamist vote-bank politics held a virtual veto over the decisions of the central government.

Every so-called secular political formation, in one way or the other, joined the Islamist bandwagon.

Though it was only in May 1986 that the Supreme Court verdict on Shah Bano was finally set aside by the Rajiv Gandhi government, the direction of the government's policy was clear months in advance.

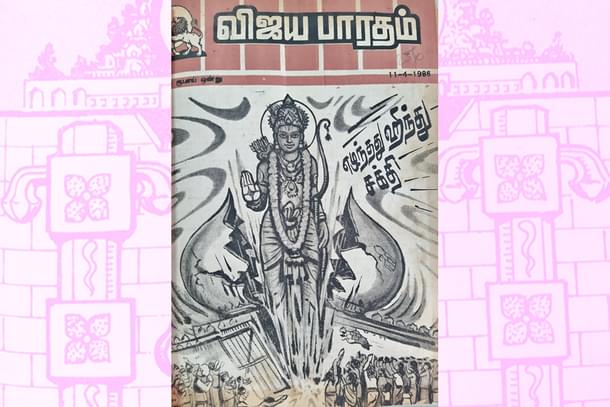

In 1985, an awareness campaign on the Ayodhya issue was launched by the VHP.

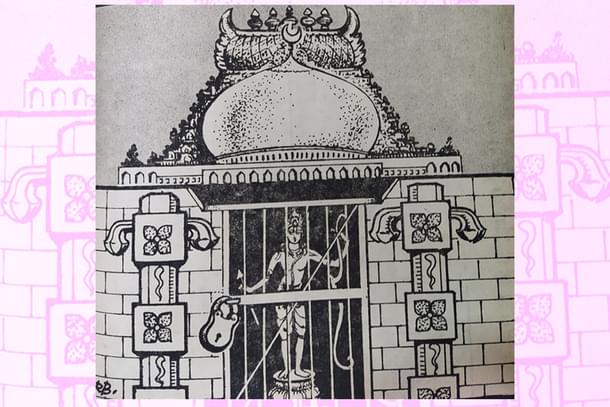

Called Ram-Janaki Yatra, the main slogan of the campaign was ‘tala kholo’ (open the lock). Shri Rama was imprisoned in his own place of birth. He had to be liberated.

February, 1986. The Faizabad district magistrate ordered the opening of the Shri Rama Janmabhoomi complex to the devotees. From 1949 onward it had been a functional temple. This victory in 1986 was the first legal triumph in a long struggle.

But the response of the then Indian state even to this significant but minor success was one of repression.

In June 1986 the administration of Uttar Pradesh under chief minister Veer Bahadur Singh took away three of the six rathas or ceremonial chariots of the Ram-Janaki Rath Yatra.

The rathas headed for Lucknow were impounded at Ayodhya. More than 20 companies of the Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) were on the look out.

The contrast was as clear as daylight.

In May of that year, the Congress government at the Centre had overturned a Supreme Court order to appease Islamist fundamentalists. But just two months later in June, the Ram-Janaki chariots were impounded and kept under police control at Ayodhya.

The writing on the wall could not have been clearer. Nehruvian secularism was not secularism but a tendency of the state to agitate against even the basic rights of Hindus while appeasing Islamists at the same time.

In such a setting, liberating Shri Rama from the domed prison imposed on him by a foreign invader became synonymous with liberating India from the clutches of pseudo-secularism.

Why 1987 Was A Landmark Year

25 January, 1987. The Ramayana was telecast as a serial in the only available national television network.

Every Sunday morning, the nation stood still from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. People gathered around the television sets. Those who had no television were welcomed into the nearby houses of those who did. There were reports of attacks on electricity supply stations if there was a power failure during the telecast of Ramayana.

In terms of technical expertise, the show had much ground to cover even by the standards of the 1980s. The horses were skinny. Except the main characters like Hanuman, Sugreeva and Angad, the vanara sena was even skinnier. Vaccination marks could be seen on the shoulders of Arun Govil who acted as Shri Rama. But beyond all these, there was sincerity and bhakti of Ramanand Sagar which compensated for all these shortcomings.

The Ramayana became a phenomenon the likes of which were not seen before and haven't been ever since.

By serendipity, the telecast of Ramayana came at an important time. The song in the show that plays in the background as the army of Rama marches into Lanka, ‘Har Har Mahadev, Ramji ki sena chali’ became a virtual anthem across India.

Long, Long Way To Go

Still, the Ayodhya movement was in a nascent stage organisationally. It could have concluded as such had the site, that was in no way a place of any special significance to the Muslims, was handed over to the Hindus.

It could have earned for Muslims tremendous goodwill among every Hindu pilgrim who would ever visit Ayodhya.

If the Muslims in Ayodhya were left to themselves, they would have. But it was not to be.

The March of 1986 saw the formation of the Babri Masjid Action Committee which asked Muslims nationwide to observe mourning against the Faizabad district magistrate judgement.

Then, in March 1987, bolstered by the victory in having the Supreme Court judgement on Shah Bano reversed, a mammoth rally, attended by approximately three lakh Muslims, was held at Delhi’s Boat Club. They demanded that the domed structure in which Shri Rama Lalla idols were present, that is, Shri Rama Janmabhoomi, be handed over to Muslims.

Until this point there was no political organisation on the Hindu side. The BJP of course supported Rama temple but had not passed a direct resolution. That would be only in 1989.

While organisationally and politically the movement was yet to be seen on the horizon, by the late 1980s the collective psyche of the nation was ready to witness and undertake such a struggle.

More than an organised movement or a political programme, the Ayodhya struggle should be seen as the Hindu self of the nation reasserting itself. A self that naturally sought its self-expression after independence but which was denied to it.

Shri Rama Janmabhoomi movement was the choice of this Hindu self. It was not the VHP, it was not the RSS, it was not the BJP that made the Ayodhya movement. Rather, the Ayodhya movement made all these organisations and political parties as its instruments.