Politics

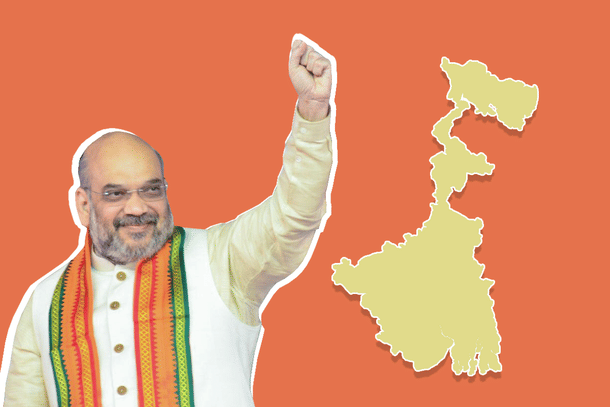

Battleground Bengal: This Crucial Poll Promise Of BJP Is Driving Passionate Support In North Bengal’s Hills And Dooars

Jaideep Mazumdar

Apr 01, 2021, 04:18 PM | Updated 05:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) poll promise of setting right a grievous wrong perpetrated on Gorkhas, tribals, Rajbongshis and other vulnerable communities in the hills and Dooars areas of North Bengal has generated another wave in favour of the party.

In its manifesto, imaginatively titled Sonar Bangla Sankalp Potro, the BJP has made a promise that is not only a major political game-changer, but will impact the lives of more than 10 lakh families in the hills and Dooars.

The BJP has committed itself to giving parja pattas (land deeds) to tea garden workers living in the hills and Dooars, forest dwellers and other marginalised and backward communities like the tribals, Rajbongshis, Koch, Meches and Totos.

This has been a long-standing demand of the lakhs of poor and landless families living in the hills and the Dooars.

Darjeeling Lok Sabha MP Raju Bista, who has raised this issue many times on the floor of Parliament (see this and this) and had taken it up with the Union government, told Swarajya: “This will mark the fulfillment of a long-pending demand, and an aspiration, of lakhs of landless families in this region”.

Gorkhas and tribals from the Chotanagpur plateau have been working in the tea gardens of Darjeeling Hills and the Dooars since the British days. They were given small plots of lands to build their dwellings within the gardens by the managements of the estates.

However, even after living in those dwellings for generations, they have no claim over the plots they stay in. In fact, they dwell in their houses at the mercy of the management of the gardens.

“Every family living in a house within a tea garden has to provide at least one member of the family to work as a labourer in the garden. If a family fails to do so, it has to vacate the house it stays in,” explained Santosh Pathak, president of a union representing tea garden labourers.

With wages in the tea gardens being very low — lower than the minimum wage under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) — working as labourers in the tea gardens became very unattractive.

“While the first generation workers who settled down in the tea gardens were largely illiterate, subsequent generations became literates. They aspired for better vocations and lifestyles, but were forced to work at low wages in the gardens because not doing so would have meant losing their dwellings. They are bonded labour of sorts,” explained Pathak.

It is also grossly unfair, said Bista, that despite living in their houses for generations, the tea garden labourers had no rights to their homestead lands.

Even encroachers or tenants acquire rights to the lands they stay in if it has been in their occupation for 12 years (in case of private land) or 30 years (in case of government land).

Many tribals and backward communities who were engaged by the British as labourers in forests were given plots of land within or in the periphery of forests to build their dwellings. But they, too, have not got the deeds of the plots of land they have lived in for generations.

Another discriminatory British-era regulation that will automatically get scrapped once parja pattas are handed out to landless Gorkhas and other marginalised communities is the bizarrely named ‘District Improvement Fund’ (DIF) lease regulations.

The Darjeeling Hills was designated an ‘excluded area’ — an area directly administered by the Governor and over which elected provincial governments did not have administrative and legislative control — by the British.

The administrative heads of districts (ie, the district magistrates) that had these ‘excluded areas’ were empowered to collect land taxes from the areas and the revenue collected used to be deposited in a ‘District Improvement Fund’ (DIF) meant for executive development works in the ‘excluded areas’.

The land taxes collected from ‘excluded areas’ have been much higher than the rate of taxation of agricultural and non-agricultural land that fall in revenue zones under the land reforms department.

For some idiosyncratic and inexplicable reason, Darjeeling Hills continued to be an ‘excluded area’ where land could only be leased to individuals or entities. No land in ‘excluded areas’ has been freehold land that can be bought or sold.

Residents of the ‘excluded areas’ have been agitating for a long time against this regulation and demanding its revocation.

According to Bengal government rules, land in the ‘excluded areas’ can be leased for only eight years and the lease amount is as high as Rs 92 per square feet in Kalimpong town.

Residents of ‘excluded areas’ have been demanding that the basat parjas (deeds of residence) be converted into raiyat parjas (permanent land deeds) for a long time (read this).

Around two dozen mouzas in Darjeeling and Kalimpong districts are still ‘excluded areas’, more commonly called DIF lands.

There have been widespread allegations of large-scale leakage of revenue collected from ‘excluded areas’ since the taxes collected from these areas are not deposited in the consolidated fund of the state.

“Residents of leased land in the ‘excluded areas’ and tea garden workers who don’t own the land they dwell on are a severely disadvantaged lot since they cannot get any loans to even renovate or repair their houses and cannot mortgage the land they stay on to avail of bank loans for business or education. This is completely unfair and highly discriminatory,” said Bista.

Bista said once parja pattas are provided to residents of DIF lands, the rules governing tax collection and administration of ‘excluded areas’ would automatically become redundant.

The BJP’s manifesto also promises to grant permanent land rights (parja pattas) to workers staying in cinchona plantations. A few thousand families stand to benefit from this.

“Getting a parja patta and thus becoming owner of the land a family stays on is a positive life-altering development. The change in a person’s status from ‘landless’ to ‘landowner’ is huge and has massive social and financial ramifications for the family,” said Bista.

Another point in the manifesto — the establishment of ‘Uttor Bongo Development Board’ for the North Bengal region will help the BJP garner a lot of support.

Mamata Banerjee had set up a North Bengal Development Department headed by a cabinet minister, but that remained mired in bureaucratese and functioned as just another government department which does little.

“The board that we have promised for North Bengal is different and will have a clear-cut mandate to formulate development and welfare schemes and projects that will have a fixed time frame. The proposed board will have representation of all sections of the people of the region and will function as the nodal agency for accelerated development of North Bengal,” said BJP state chief Dilip Ghosh.

Yet another winning point for the BJP is the commitment in the manifesto to increase wages of tea garden workers to Rs 350 a day. They now get Rs 202 a day.

“Despite countless requests and representations, Mamata Banerjee did not increase the wages and sided with the owners of tea gardens. A tea garden worker gets much less than the minimum wages for workers prescribed under labour laws. Plantation labourers in other states, including Assam, get much more,” said Bista.

The BJP has also promised to set up a grand Gorkha Freedom Fighters Museum in Darjeeling. The museum will showcase the contributions and sacrifices of Gorkhas in India’s freedom struggle.

The museum will also have sections dedicated to Gorkha soldiers and officers in India’s armed forces highlighting their valour and feats.

The promises of a ‘permanent political solution’ to issues related to the Darjeeling Hills and Dooars, and bringing 11 Gorkha groups in the list of Scheduled Tribes (STs) has also added a lot of tailwind to the BJP’s sails.

“The manifesto is a winner for us. There was a strong current in our favour, but this manifesto is a game-changer. And the promises, once implemented, will change the face of North Bengal and the plight of the people of the region,” said Bista.

The promises in the BJP’s manifesto have also taken the wind out of the sails of the Trinamool in the Dooars and Terai areas of North Bengal and the two factions of the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha in the Hills.

Jaideep Mazumdar is an associate editor at Swarajya.