Politics

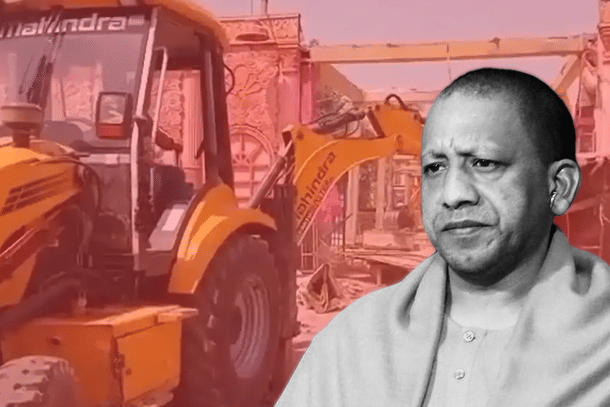

Bulldozer Politics Is A Statement, Not A Solution

Tushar Gupta

Apr 19, 2022, 05:57 PM | Updated 05:57 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

It all boils down to maintaining the right balance between the carrot and the stick. The state, generous in its deployment of carrots, and rightfully so, must not shy away from looking to exercise the use of the stick against elements that disrupt the social harmony and cause economic disruption.

However, after the events of the last few days, the question is how far the state can go in improvising the stick and if the whole idea of ‘bulldozer justice’ is sustainable or not.

Hindu processions in several parts of the country have been under attack. The videos surfacing from ground zero are a testament to the underlying communal faultline politicians want to either ignore or deny the existence of. Beyond law and order, the question is now of processions versus the stones.

As per some politicians and media groups, the Hindu processions are the problem since they choose to go from ‘Muslim areas’, are provocative, and make the mistake of celebrating their religion before a mosque or members of other religious communities. Put simply, the logic being dictated is that if a community feels provoked, they have all the right to pelt stones, even on women, children, and law enforcement agencies. The processions are the crime, but the stone hurling violent elements are not.

The narrative being peddled in support of stone pelting is in continuation with the political hypocrisy and victimisation of one minority that has become a trademark of the opposition in India today.

Thus, the women sitting in Shaheen Bagh, imagining the citizenship of 200 million Muslims being taken away, are hailed as caretakers of democracy and humanity, while Hindu women persecuted, raped, kidnapped, and forcefully converted daily in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh are forgotten.

Similarly, halal meat is hailed as the holy diet for the nation, imposing the will of the 20 per cent on the rest of the country, while even the question of banning non-vegetarian food during Navratri is dismissed as communal.

The idea of equality in schools is branded as fascist to defend the use of the hijab. Many were against the medical workers and doctors attacked and were chased away during the Covid-19 pandemic when they approached certain residential areas.

A religious chant five times a day on loudspeakers is critical to the social fabric and secularism of the country, but Hindus must seek permission for their chants and not have their processions pass through certain localities. Crackers on Diwali warrant criminal proceedings in the name of environmental preservation, but slaughtering of animals is above inclusiveness. The list goes on.

The majority of voters, exhausted by the same drama, see right through the unapologetic shallowness of the narrative and the shamelessness with which it has been normalised. Thus, when the bulldozers were mobilised to demolish the homes of the rioters built on illegally occupied lands, there was a hushed cheer online in favour of the government.

The opposition and the critics may want to cite the legal mumbo-jumbo, question the need to demolish homes on illegally occupied lands to punish the rioters, and they may have a case as well, but aren't they the ones that encouraged it in the first place?

One can’t hail the events of Shaheen Bagh that culminated into a full-blown riot in the national capital and stalled the notification of the Citizenship Amendment Act, or hail the farmers of Punjab, who sat on the Singhu highway for almost a year, caused economic losses to the tunes of many thousands of crore, wreaked havoc on Republic Day, damaging public property and injuring scores of policemen, and stalled a reform that would have had a progressive impact on 50 per cent of the working population and 15 per cent of the GDP contributor, and then question the solution of the bulldozer.

There is also the question of cost. The ones questioning the economic cost of demolished houses were ignorant of the plight of businesses and other groups who relied on the highways the farmers had occupied for a year. They were silent when ambulances struggled to pass through Shaheen Bagh, or when students appearing for their exams had to take a longer route to schools.

While they were choosing to be ignorant as losses kept piling up, both to the public and the private sector enterprises, they today thump their chests in melodramatic angst to defend the rioters. The government is well within its right to recover the cost of damages, and this is where the bulldozer becomes a statement, but is it a solution, one that has a long-term answer to a long-term problem?

The Indian state finds itself in a unique situation today. Domestic faultlines are not unique to India, but neither is the Indian state operating or can afford to operate like the Chinese do, clamping down on every dissenter and protesting voice nor is our law and order modelled on the American lines, where the work of the law enforcement is not hindered by politics or constrained by the lack of resources. And yet, the state machinery has to deal with growing civilian pockets across India where both the application of law and order and mere accessibility are difficult.

The bulldozing of rioters’ houses built on illegally occupied lands or to recover costs as mandated in the law ushered by a few state governments is a punishment, but is it a deterrent, especially in the troubled pockets, like Jahangirpuri or Seelampur in the capital where the riots were carried out? Tomorrow, what if the mob is not of fifty people but five hundred, five thousand, or fifty thousand people across a state, indulge in communal rioting or clashes?

The bulldozer solution is not equipped for that situation, nor can the government, even if there is a law, go around demolishing thousands of houses. Yet, a solution must be found.

To begin with, the Indian state machinery must upgrade its surveillance infrastructure. Already, cameras and drones are deployed in troubled pockets post-clash, but the infrastructure needs to be preventive and not reactive.

In cities, beginning with the capital, aerial and digital surveillance through drones, cameras, CCTVs, and patrol vehicles needs a necessary upgrade. From something as trivial as a GoPro action camera to something as intricate as a UAV, the police departments must be equipped to monitor, assess, and respond to any situation, especially during festivals and other important days.

This will not only aid the process in the courts, but also act as a deterrent. Furthermore, the government, in deliberation with other enforcement agencies, willing opposition parties, local councils and panchayat, must consider the idea of barring rioters and arsonists from public welfare schemes altogether, appearing from government exams, owning a passport, flying domestically, and having access to formal finance.

Given how women and children have been scapegoats in the recent protests, the government could be forced to debar an entire family, or the members above 18 years of age, from the above unless one of the members reports to the local police. If the threat of the bulldozer enables a suspect to surrender, the thought of being debarred from an array of services must act as a deterrent for any troublemaker. There must be some punitive costs and measures.

The state, and the state alone, must have a monopoly on violence, and yet, in Jahangirpuri, the Delhi police had to work against some resistance while conducting their duty. The question of resisting law enforcement agencies or blocking their access, as was the case during the Singhu protests also, must not be normalised. In any area, where any law enforcement agency is denied access in the wake of such events, the government must consider the idea of blocking all essential utility services and supplies. For instance, in Singhu, until the farmers agreed to move a designated protest site, all electricity, water, and internet should have been blocked.

No community can claim ownership of any area and dictate access to it. Proper application of law and order must not be attacked in any part of the country.

The attack on Ram Navami processions is no surprise, but a continuation of the events that began with the intolerance debate in 2016-17. Since then, vested interests have been looking to derail India’s growth trajectory by mobilising local elements and ushering unrest and political chaos.

For a country looking to invite businesses of the world and become a $5 trillion economy, attacks such as this are unacceptable and must be prevented, and therefore, within the purview of the law, the state must take the necessary hardline.

The Modi government, irrespective of religion or caste, has been generous with the carrots, and for that very reason, they must not shy away from using the stick, when necessary. As evident from Uttar Pradesh, they have the mandate to do it. To punish swiftly is good, but to deter is great.

Also Read: Not Minority Rights, But Equal Rights: How Modi Government Missed Its Cues In Supreme Court

Tushar is a senior-sub-editor at Swarajya. He tweets at @Tushar15_