Politics

Colonialism In Our Museum Exhibits: A Case Study Of A Chariot

Aravindan Neelakandan

Aug 22, 2020, 04:42 PM | Updated 04:45 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

I stand before the ‘thaer’ or rath — the chariot.

It is a wooden chariot — like any other chariot from any other Hindu temple. Compared to the huge chariots of some temples, this chariot is modest by size, but in terms of the wooden carvings and designs, it is very much as divine and as exquisite as any other.

Only, the description does not say that.

The chariot I was standing before is an exhibit at the Government Museum, Kanyakumari. The description kept along with the chariot is in English, filled with typographical errors.

However, it states something quite amusing:

According to Ayya Vaikundasamy cult, there is one God — the supreme power, God has no form. One must see God in one’s own image while standing before a mirror. According to him no deity worship should be practiced. Accordingly, no deity figures are found in this Temple Car. But, the wood carvings represent figures of Yallis, Musicians, Sages, Women folks, Worshippers, Kings and Soldiers. This is a peculiar (sic) to this Temple Car.

So it says that this may look like a Hindu sacred chariot, but it is not as Hindu as it looks. It is different.

It is more 'humanistic' than Divine, more 'secular' than sacred. It has no place for 'supra-human divinities'. In other words, it is more protestant in a non-Hindu way.

But as I go around the chariot and look closely at the wooden sculptures, they say a diametrically opposite story.

I see sage Narada. I see a sage holding a Shiva linga. The sage holding the Shiva linga has a beautiful turban-like crown and a Vaishnavaite-looking sacred mark on his forehead.

Then, there are Garudas with subdued serpents as ornaments.

A Garuda is flanked by the Yalis — the Hindu dragons, thus underscoring the special importance of Garuda:

There are also sculptures of Parashurama, and Sri Krishna stealing the dresses of Gopis — a scene from Srimada Bhagavatam itself:

All the above facts about the exhibit show it to be as Hindu as any other Hindu temple chariot.

Yet, why is such a statement accompanying the exhibit kept there?

The seemingly simple lines here betray deep prejudices and colonial stereotypes of hatred, which are getting perpetuated to this day.

The ‘Iyya Vazhi’ (Way of/shown by Iyya’.) is a vibrant socio-religious movement which emerged in South Travancore in the 19th century.

It was started by Iyya Vaikundar (1809-1851), the spiritual name of Muthukutty Swamy, who is venerated by his followers as the 'Avatar of Narayana'.

The movement organised the people irrespective of jatis into an effective spiritual community disseminating the message of freedom, spiritual oneness, and fight against injustice — both socio-economic degradation and proselytising.

Of late, there has been a movement to declare Iyyavazhi as a separate religion. While the immediate reason is the fear of the temple being taken over by HR&CE as well as the lure of minority concessions, the larger motive is the anti-Hindu paradigm advocated by the colonial-evangelist movement.

To understand the entire problem in context, one has to look back into history: almost 150 years.

The East India Company had, by then, become the real ruler of Travancore. The economic exploitation by East India Company was done with the princely State as the proxy.

The resulting degradation of the society was exploited by institutions like London Mission Society (LMS) and Society for the Propagation of Gospels (SPG).

Here are a few instances:

On the one hand, the British Regent compelled the Travancore government to pay the British Rs 800,000 annually as protectorate, forcing the princely State to levy new taxes, like for example, palm tree tax, which in 1807 CE alone, fetched Rs 18,523.

Further, to pay the East India Company-demanded annual protectorate, communities like Ezhavas, Channars, Cherumars, Chambavas and Pulayas were made to pay individual head tax for every one in the age of 16 to 60.

And under this tax, Rs 163,000 was collected annually. In this, the government exempted the powerful landed communities: Nayyars, Vellalas, Muslims and Kanmala communities.

In the early decades of the 19th century, then the Travancore regent, Col. Manroe, made quite a few concessions for the converted Shanars.

On the other hand, he lowered the market price of foodgrains. But he refused to proportionately lower the taxes the paddy producers had to pay.

Such acts, designed to make intra-community relations deteriorate, created an environment that made evangelism possible.

A section of society was made to believe that the native religion, culture and state were subjugating them, while the colonial and evangelical masters were here to 'liberate' them.

The power imbalance in intra-community relations in the Travancore society, which were dictated by local politics and socio-economic dynamics, got blamed on Hindu Dharma — now characterised as the 'heathen religion of idolatry' designed by priests to 'exploit' people.

The colonial missionaries and then the colonised social historians, right through the Nehruvian and Dravidian decades of designed cultural illiteracy, have continued this propaganda religiously and slavishly.

It was in such a situation of the 19th century Travancore that the Iyya Vaikundar movement arose.

Vaikundar was, perhaps, the first Hindu critique of colonialism and the vested interests of social stagnation which colonialism was breeding in India.

He called the former — 'Ven-Neesan’, white-skinned evil-doers and the latter ‘Kali Neesan’ — the evil-doers of Kali Yuga. He stated that the former had destroyed nations and now was destroying the social fabric, affecting the livelihoods of the communities like Chantoor (Chanar, Nadar).

He associated these two with the 'Asuric' characters from Hindu ithihasas and purana tradition: Ravana, Duryodhana and Sura Padman (Skanda Purana).

This is a very innovative critique of colonialism, related evangelism and social-stagnation.

Epigraphy scholar S.Ramachandran and community historian Ganesa Nadar explains:

Iyya Vaikundar calls his people ‘Children of the eye’. This is not simply a call of endearment, but has a mythological motif weaved into it. Ancient inscriptions speak of Chanars as ‘Eye-Chanars’. Upamanyu Bhaktha Vilasam calls them as ‘Witnessing Clan borne Nobles’, ‘Preceptors of (martial) arts’ etc. It is this tradition that is being recognized and revived by Iyya Vaikundar’s call of ‘Children of the eye’. ‘Iyya Vaikundar obtained Maha Samadhi on 1851 June 3 (Kerala Calendar: Vaikasi 21 Kollam 1026). During his last days, he was at a village called Osaravillai where he established a temple similar in its numerical dimensions to the Chidambaram Temple — which was the traditional coronation centre of Chola kings. Similar to the Lingam of ether or space in Chidambaram, Iyya Vaikundar established a roof with 96 fittings, symbolizing the Chithasa beyond the 96 principles in Saivaite Siddhanta. Vaikundar proclaimed his Dharma Yuga rule — rule of the righteous eon from this village. He had already condemned proselytizers as being ignorant of Chithakasa concept which pervades all existence. His establishment of this place of worship with such symbolism was a reaffirmation of this truth.Shoulder Cloth Rebellion: Unknown facts and known lies (Tamizh), South Indian Social History Research Institute, p.116, pp. 118-9

Vaikundar advocated strong vegetarianism, insisted on cow protection and condemned proselytizing by Protestant evangelists, Catholic Church and Islamists.

He predicted more than 150 years ago that the exclusive drive for global domination between Islam and Christianity would result in their mutual destruction.

He also stated that India as a whole would become independent and flower into a 'Dharma Yuga' and the flag he gave was the saffron flag with a white Vaishnavaite mark in the middle.

The missionaries who were having a field day amidst the Nadars of South Travancore were stopped in their tracks by this movement.

Iyya Vaikundar was arrested by the Travancore prince and the seer was subjected to torture.

In the present narrative, the arrest was made because so-called caste Hindus instigated the monarchy or the king himself got afraid.

A good example of this narrative fixing is the academic work done by Dr. G. Patrick of the Department of Christian Studies, Madras University. He states:

Against the background of the growing popularity of Muttukutti and the convergence of people around him in multitudes, a complaint seems to have been preferred against him to the king. The king seems to have ignored the complaint initially, exclaiming whether it was possible for a Chanan to ‘become an incarnation of Vishnu.’ But given the reality of an already weakened monarchy due to the dominance of the colonial power, the king could not remain unperturbed at his seeming challenge.G. Patrick, An Inquiry Into Ayya Vali A Subaltern Religious Phenomenon In South Tiruvitankor, Madras University, 2001, p.112

Strategically Dr. Patrick adds the following in the footnote:

There is an information from oral tradition that the king took action against Muttukutti at the behest of the British power to which LMS missionaries had petitioned in this regard, because the growth of such a religious phenomenon was a hindrance to their missionary enterprise. I did not find any data on this in AT or LMS reports. However, that there was a Government interference to arrest the spread of this phenomenon of AV is attested to in the LMS Report of 1838 which reads as: ‘The Government, however interfered, and the excitement quickly died away.” — LMS Report for the year 1838, p.71.ibid.

The above attempt appears to be an exercise in academic sleight of hand.

Actually, the then missionary reports quite clearly stated that the reason and the pressure for the arrest came from East India Company administrators.

The notorious evangelist, Robert Caldwell, wrote in his 1844 report of 'a worker of lying wonders' who was 'a Shanar of the name of Mootoocootty'.

He calls the spiritual path as 'a distorted heathenish imitation of Christianity'. Here we see the evangelical imperialistic impulse to dismember every Hindu social and spiritual movement from the Sanatana spiritual stream.

He shows the natural Christian contemptousness. Their prayer to him sounds as 'screaming and dancing.' He identifies Iyya Vaikundar and his followers, as 'the most active and eager opponents.'

Then, Caldwell goes on to claim of Iyya Vaikundar thus:

Mootoocootty and his disciples, originally twelve, the inspired representatives of this deity, profess to foretell all events, to avert calamities, and to cure all diseases by giving the sick persons copious draughts of cold water. The person was an apostate Christian, and did his best to induce the people to think of him ‘the great power of God.’ Heathens flocked to him from every quarter in considerable numbers and some Christians in the neighbourhood, partly from curiosity, were tempted to visit him. When the delusion was at its height, the prophet began to prophesy the overthrow of the Company’s government and a golden age of light taxes. This led to the interference of the authorities and the prophet’s downfall.Robert Caldwell, Mission of Edeyenkoody, in the district of Tinnevelly and Diocese of Madras, SPG, London, 1844:47, pp.20-2

One should note here that Iyya Vaikundar had asked his followers to work for the overthrow of the British.

Further, it is quite fascinating to see that through the Dharmic discourse, couched in Puranic language, Iyya Vaikundar had correctly identified the root cause of then socio-economic malaise as the heavy taxation imposed by the British East India Company through the Travancore State.

It is a understanding far more correct and more holistic than the most of the university-educated British Indologists then and the JNU educated leftists now.

He was, perhaps, preparing for a civil disobedience movement. Caldwell also had made it clear that it was the anti-British stand of Vaikundar which invited action against him.

Yet another report too states:

This impostor’s name was Muttukutty. By some clever artifice, he contrived to get himself talked of as a worker of miracles, and, as his fame spread abroad, numbers flocked to him. He announced himself as an incarnation of the god Naraiyanan; forbade idolatry and said that men were to worship only himself. He also sent out disciples, two and two, into Travancore and Tinnevelly, to proclaim his miraculous powers and set up his worship in such villages as were disposed to receive them. One of the disciples pretended to be an incarnation of Hanneman, the monkey-kind so celebrated in Hindoo mythology and in a village not far from Courtallam, used to sit up in a tree all day and run about the village in the evening. Persons and parties went in consequence to the chief impostor from many places, prostrated themselves before him...and I regret to add, that a few individuals among the converts in both Missions, suffering from diseases which they had tried in vain to remove were also tempted to resort to him. Some cures no doubt were performed, as in such cases they have often been: ...His fame continued to increase, and...Growing bold also, by his successes and perhaps believing his own lie, he and his disciples began to teach sedition, declaring that the man was born who would put an end to the rule of the East-India Company in India. Reports of these things spreading in Tinnevelly, reached the ears of the Collector; who felt it his duty to inquire into the statements which had been circulated and to ascertain with whom they originated. Having communicated the result of his inquiries to the Travancore government, the Rajah caused Muttukutty to be apprehended and put in confinement; from which time the delusion gradually died away.George Pettitt, The Tinnevelly Mission of the Church Missionary Society, Seelyes:London, 1851 pp. 265-8

The above mission reporter was indulging in wishful thinking when he wrote that the movement ‘gradually died away.’

After Iyya Vaikundar left his physical form for Vaikunda, the movement continues to be reported by the Missionaries as a great impediment to their proselytizing activities.

Not just men, but women and also widows had become epicenters of Iyyavazhi. A missionary report dated 1858 records:

There is a widow living at this place who was a follower of Muthukutti. She was also a fortune-teller and pretended to cure diseases by incantations. She allowed her hair to be matted like that of Pantaram, abstained from fish on Tuesdays and Fridays, performed ablutions in the sea, sang for four or five hours together in honour of her swami and was occasionally under the influence of the devil.Report of the Santhapuram District for the year 1858: [ARTDC for the year 1858: Nagercoil: London Missionary Press, 1859, p.4-5.

Every feature, structural, ritualistic and spiritual, has been, since 1850s to this day, well rooted in Hindu spiritual tradition. Let us consider some of the prominent features:

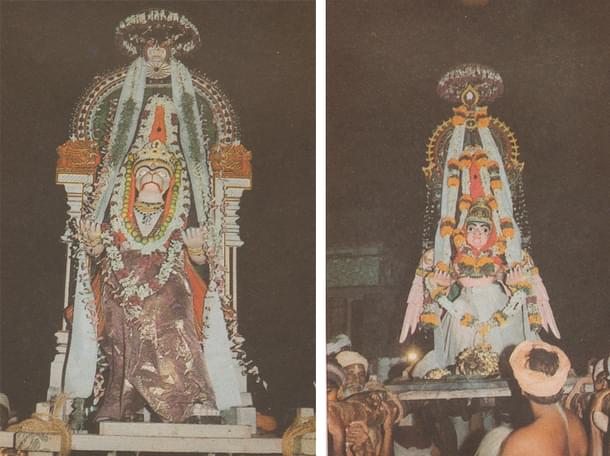

The different Vahanas or mounts for ceremonial royal procession of Deity (here aniconic Vaikundar) during festivals shows how deeply Hindu the Iyyavazhi movement is.

For daily ritual rounds that the Deity (Vaikundar) takes, a Vahana is decked with saffron flags. Then during festival, Vaikundar comes in different Vahanas. One of them is modelled after a temple Gopuram.

Then there are also Hanuman and Garuda vahanas — in tune with the Vaishnava tradition. Then there is also a Hamsa-vahana.

With all these elements, Iyyavazhi combines all the forms of Hindu Dharma then known.

While colonialism and its integral component — evangelism — essentialised Sanatana Dharma by the characteristics of social stagnation then prevalent in the South Travancore State, Iyyavazhi demonstrated the dynamic nature of Dharma by creating a Puranic framework for understanding society, its dynamics and colonialism as well as evangelism.

Though Vaikundar was well aware of Christian and Islamic prophetic traditions, he chose the Dharmic tradition of Avatar and Yugas as categories to understand the societal problems and emancipate the people.

For the missionaries, they have to explain how the supposedly superior Christianity, with the support of the entire Empire, was stopped in its tracks by what they considered as a small pagan cult.

As we have seen, the tone was set by none other than Robert Caldwell, the Godfather of Dravidianist racism.

Seven years after his Vaikunda-departure In 1864, another mission report spoke of Iyyavazhi as 'a modern sect greatly on the increase.'

In the 'Report of the Kottaram Mission District for the year 1871', one finds mission evangelist, one Mr. Nathaniel, lament the continued increase of Iyyavazhi in several places around the mission.

Santhapuram missionary district mission report of the year 1864 states this:

Some years ago, a Palmara climber named Muthukutty claimed to be the incarnation of Vishnu and deceived many people. His followers had erected pagodas in many places. As they regard Muthukutty as an incarnation of Vishnu, they affirm that the worship of Muthukutty is really a worship of the supreme being. This impostor is one of the chief obstacles to the spread of the gospel in these parts.

They started setting the narrative that Iyyavazhi was radically different from Hindu Dharma.

Samuel Mateer, a fanatical missionary writing in 1871 spoke of Iyyavazhi as 'a curious phenomenon in the religious history of Travancore' and as an absurd medley of Hinduism and Demonolatry, with a slight tinge of Christian element.'

Labelling it a 'superstition', he called Iyya 'a poor Palmyra climber who laid claim to be an incarnation of Vishnu'.

Then, he acknowledged that 'this singular people display considerable zeal in the defence and propagation of' their religion which he again characterised as 'destructive errors.' (Samuel Mateer, '”The Land of Charity:" A Descriptive Account of Travancore and Its People, with Especial Reference to Missionary Labour', Snow & Co., 1871, pp.222-3)

By 1874 they — the missionaries — even gave the Sampradaya a new name:

It was in the village comprising this (Thamaraikulam) section that the gospel gained its earliest conquests in South Taravancore. Progress was rapid. Congregation were formed and adherents come over in great numbers. In 1821 there were upwards of 1200 converts in these places. It seemed as if the whole population would soon be brought under the influence of the cross. But a terrible check was given to our operations by the rise of Muthukuttyism. Lastly, a car festival was instituted at Kottayady to which thousands are annually drawn from the towns and villages far and near. This cunning contrivance of Satan has much impeded our progress in these parts and is still a great power of darkness against which we have to wage unceasing war.[Emphasis added]: Reports of the Nagercoil Mission District: 1874

Thus they tried to show the movement as a distortion of Christianity to hide their own defeat.

Right from the colonial proselytizers to present day mentally colonized Nehruvian-Marxist historians, the Iyyavazhi movement is problematic for their extremely distorted even diseased narrative of Hindu social history.

The colonial-evangelical narrative is that the people of so-called low castes were exploited by the rulers and priests through caste system for millennia and the missionaries came as their liberators.

This is the dominant narrative even today. The recent controversy over Nadar community in the CBSE syllabus springs from this blinkered view of history.

For the leftist-Nehruvian-Dravidianist historians, politicians, Hinduism should be shown only as incapable of reformation and as fundamentally flawed.

But here is a phenomenon that is more rooted and more holistic than any framework for history any Nehruvian or Marxist had come up with, not to mention the abjectly pro-colonial pseudo-rationalism of the Dravidianists.

So they too try to either completely erase the movement from the history or distort it as a new religion unrelated to Hindu Dharma, but influenced by Christianity.

So, those lines in the museum exhibit contain within it this century and a half old bias against Hindu Dharma and radiates the divide-and-convert policy of proselytizers.

How easily these falsehoods are inserted into our mass psyche even in the face of bright light of truth is indeed a worrisome phenomenon!

Sources:

- The socio-economic data in the article comes from the book by Sri Ganesan Nadar & Sri S.Ramachandran: ‘Shoulder Cloth Rebellion: Unknown facts and known lies’, (SISHRI, 2011,Tamil).

- Photos of various Vahanams of Vaikundar from: ‘Iyyavin Vahana Pavani’, (Tamizh) V. Radhakrishnan, Vijayaraj Publications, Kanyakumari

- Most of the mission reports taken from the PhD thesis of Dr. G. Patrick of the Department of Christian Studies, Madras University.]

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.