Politics

Decoding PM Modi’s Speech In Sri Lanka: Seeking A Radically Positive Engagement

Aravindan Neelakandan

May 13, 2017, 08:21 PM | Updated 08:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Going through the speech Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered in Sri Lanka to the large mass of Tamils assembled there, thrills me as a Tamil and as an Indian. At last we have a Prime Minister who understands the historical roots of Tamils and the social dynamics and needs of Tamil society. The speech was an excellent mix of spontaneous love for one’s own people and a humane realisation of their agony and aspiration.

When the Prime Minister addressed about 30,000 Tamils in the Central Province of Sri Lanka, he became the first-ever Indian prime minister to do so. And these are the Tamils who have been betrayed by the politics of mutual national self-interest, myopic in the case of India and unethical and inhuman in the case of Sri Lanka.

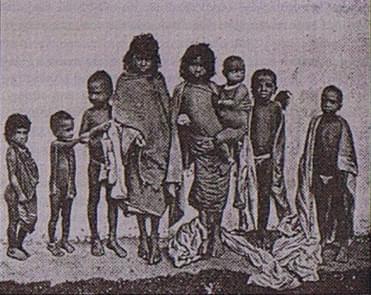

These Tamils are mostly of mainland Indian origin. British colonial rule in South India was creating a series of famines back in the day. This same regime was also creating tea estates in Sri Lanka at the time. So, despite the subhuman conditions in Sri Lankan tea estates, Tamils migrated there in large numbers.

British historian Ray Moxham has provided some heart-wrenching statistics on this massive human migration. For example, in one year alone, 272,000 Tamils arrived as coolies for work in tea plantations. There were 133,000 departures. About 50,000 stayed in Sri Lanka, 70,000 died. Tea trade flourished.

Then, during the notorious 1877 famine, some 167,000 South Indian Tamils went to work in Sri Lankan tea plantations. They included women and children. When the famine was over, 87,000 of them remained in Sri Lanka. By 1900, the migrant labourers from India in Sri Lanka numbered 337,000 and most of them were Tamils. They toiled in 384,000 acres and 600 square miles of tea estates, producing 150 million pounds of tea for export mainly to Great Britain. (Roy Moxham, A Brief History of Tea, 2009).

The acknowledgement of this historical fact came through in the words of the Indian Prime Minister. “People the world over are familiar with famous Ceylon Tea that originates in this fertile land. What is less known is that it is your sweat and toil that makes the Ceylon Tea the brew of choice for millions around the globe.”

With these words the Prime Minister more than acknowledged the contribution of Tamils in making Sri Lanka a global player in the tea industry. He has reminded the world of the dark colonial history behind this sector and has asked the world to feel its indebtedness to the toil of Tamils and such colonised people the world over.

Even after independence, the fate of these poor Indians, who have not just settled in Sri Lanka for over a century but contributed to one of its global commodities, became a matter of cold bargain between India and Sri Lanka. Fearing the coming together of Tamils from India and the native Sri Lankan Tamils, Sri Lanka wanted to send them back to India. But then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru did not want them back except in limited numbers. Nor would he pressurise the Sri Lankan government much. He valued the good relationship with Sri Lanka more than the Indian Tamils who were in danger of getting caught in a stateless limbo between India and Sri Lanka. Nehru coldly proclaimed, “we do not consider them our nationals” and “we cannot function on behalf of people who are not our nationals”. He further ruled out “interfering in the affairs of another country”, which would mean “accepting them as our nationals which we don't”. Later, Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi also continued in the same vein.

It is unavoidable that we view Modi’s speech in the historical context of colonial exploitation and Nehruvian neglect of Tamil people. Modi has embarked upon a radically new direction. In his speech, he connected the sufferings of their forefathers and the survival of the present Tamil generation with the resilience they derive from the Sangham era. Then he pointed out that Gandhi, during his only visit to Sri Lanka, desired very much their socio-economic development. He highlighted the syncretic elements in Buddhist and Tamil Hindu spiritual traditions. Each statement of the Prime Minister has an elaborate subtext encoded in it. It jettisons the cold, mechanistic, strictly legal Nehruvian worldview. Modi’s vision instead calls for a humanitarian view of Tamils in Sri Lanka with whom India has an umbilical relation which can never be cut off.

At the same time, Modi called for the integration of Tamils with Sri Lanka – not as submissive minorities but equal partners who share cultural traditions and who have contributed immensely to the economic growth of Sri Lanka.

The inauguration of a new 150-bed hospital complex in Dickoya, which has been constructed with Indian assistance, shows a new commitment in the infrastructural development of the region with special attention to Tamils of Indian origin. The cultural ties are getting further strengthened with a direct flight between Varanasi – a Saivaite pilgrimage centre – and Sri Lanka. This will help both Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims; the latter can board a flight to visit Sarnath – the famous Buddhist pilgrim centre just 10km from Varanasi. Perhaps Modi government could also plan a Saivaite pilgrimage route connecting Trincomalee, Chidambaram and Varanasi. This would go a long way in empowering Sri Lankan Tamils as equal partners in Sri Lankan nation building.

The visit by the Indian Prime Minister clearly aims to achieve in Sri Lanka a radically positive strategy. It is putting Sri Lankan Tamils on an important, equal footing, and acknowledging them as an unavoidable economic growth force. India aims to play the role of a catalyst here.

Simultaneously, India also seeks to emphasise the cultural and spiritual syncretism that exists between India and Sri Lanka on the one hand and between Saivaite Hinduism and Buddhism on the other. All of this together will help India foster peaceful and prosperous regional development – a vision based on harmony and goodwill among the neighbouring countries without compromising on the welfare of the people of Indian origin.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.