Politics

Developing Jammu And Srinagar As Megacities Is India’s Best Bet To Remake J&K Into A Truly Multicultural State

Arihant Pawariya

Jun 29, 2021, 07:44 PM | Updated 07:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On 24 June, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Union Home Minister Amit Shah and Lieutenant Governor of Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir Manoj Sinha held talks with all political factions of Kashmir, a first since the President made Article 370 infructuous on 5 August 2019 and Parliament passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act hiving off Ladakh as a Union Territory (UT) without legislature and Jammu-Kashmir divisions as UT with legislature.

In the days leading up to the meeting, there were various rumours about the possible future course of action that the Centre was contemplating including reinstatement of statehood. However, the Centre had debunked such news and clarified that the meeting was to discuss ongoing delimitation process. The same was confirmed by defence analyst Abhijit Iyer-Mitra whose source was one of the leaders present in the meeting with the Modi-Shah-Sinha trio.

The Kashmiri leaders “were told that the sequence of events will be as follows: "Delimitation; Elections; Good Behaviour; Statehood,” Mitra tweeted. “No clear deadline was given for when statehood will be bestowed and any bad behaviour by these two malignant parties will be used to deny statehood,” he added.

This means that the J&K Reorganisation Act, 2019 will remain in force for the foreseeable future. The Centre might be looking to test the behaviour of the two main Kashmiri parties in a renewed democratic setup.

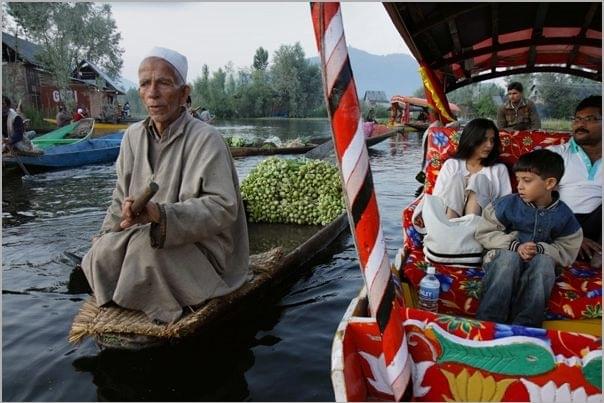

This means that the Centre, if it so decides, stands a good chance to fully integrate the J&K into Indian mainstream. This can happen only if the society in the state becomes more tolerant of diversity and multiculturalism. The best way to achieve that is rapid urbanisation. Developing Jammu and Srinagar into twin megacities in the Himalayas should be taken up as a priority project. The current population of five and 11 lakhs respectively (as per 2011 census) provides ample space for improvement considering the space for expansion of these cities into nearby towns.

The government should target inflows to J&K to the tune of ten million people in the next 10-15 years. Delhi-Katra expressway should be extended all the way into the valley via Anantnag which can be an axis that the government can set to build as special economic-cum militarised zone.

These special zones (easier to sustain in Jammu division but difficult beyond that from the security perspective) should be fully owned by the Government of India - I will explain its implication later. This Jammu-Anantnag-Srinagar axis east of the Jhelum river should be easier to develop given relative peace that prevails in the region.

It is also an area which borders Ladakh and thus easier to protect from the attacks by terrorists coming from Pakistan. The area east of Jhelum and jutting the Ladakh UT is also where most of sacred sites of Hindus exist including the Amarnath Shrine and Martand Sun temple. Given this religious attachment, it would be easier for Hindu migrants and Pandits of the valley who were driven out more than 30 years ago to settle here.

Carving out special economic zones (which also has housing complexes for migrants and Pandits) - fully owned by the Central government - should come first and foremost. It goes without saying that new settlements of migrants must be backed with heavy security that can thwart attacks by terrorists on the residents as well as the riots that may be incited to drive them out.

These zones must be declared tax havens with an important ‘term and condition’ being that the companies that setup shop there employ large number of people. A production-linked incentive scheme specifically tailored for J&K can be designed to lure foreign companies. Manufacturing industries for which raw material is readily available in the region can be prioritised. The amount of foreign money in the region will act as a security cover of its own and provide enough heft to keep the palms of troublemakers well greased.

Next, the incentives for migrant workers who are going to be employed in these zones should be there so much so that the threat perception of violence despite being protected by the military can be overcome. These can include state-sponsored and state-of-the-art housing, education and healthcare apart from income tax relief.

Moreover, all those serving in the army in J&K can be allotted houses in these settlements where their families can live along with the civilians and make use of shared resources such as housing education and healthcare facilities available to workers. To incentivise this, service conditions of the security personnel can be tweaked so that they can be deployed in one place for longer durations. It will also help their children grow attached to J&K and they can continue to stay, study and work there and become permanent citizens.

Weaponising ‘vikas’ in Jammu and Srinagar can go a long way in solving the J&K problem.

The Indian government spends humungous amounts of money both for financing military operations and development in Jammu and Kashmir. With only 1 per cent of population, it got 10 per cent of the central government funds given to all the states by the Centre from 2000-2016 (Rs 91,000 per capita). A part of the money that the government spends on J&K can be used to finance settlements for Indians as well as giving aid to industry to go there.

The question that arises now is this: does the J&K Reorganisation Act give enough powers to the Centre to make such radical changes?

Though J&K is a UT, the Centre has extended marginally more powers to it than it has to UTs like Puducherry or the National Capital Territory of Delhi. The powerful article 240 of the constitution which gives the President a veto to make regulations for many union territories without legislature and to even Puducherry (to an extent) has not been extended to the J&K unfortunately. Moreover, the J&K assembly has been empowered to make laws on the subject of ‘land’ which falls in the State List - something that’s barred for NCT of Delhi. However, like Delhi, fortunately, ’police’ and ‘public order’ have been kept out of legislative control of the J&K assembly.

The Reorganisation Act allows for Article 239A of the constitution to be extended to J&K which facilitates the LG to appoint certain number of people to the elected assembly of the UT. Like in Puducherry. This was a great opportunity for the Centre to create a way to nominate some members from the Kashmiri Pandit community but it didn’t do so. The act only allows for the LG to nominate two women members if he/she thinks women are not represented well enough in the assembly.

Nonetheless, the Centre will continue to exercise substantial control over J&K via the Lieutenant Governor. The Act states that any bill or amendment related to finances ‘shall not be introduced into, or moved in, the Legislative Assembly except on the recommendation of the Lieutenant Governor‘ including bills making provisions for any imposition, abolition, remission, alteration or regulation of any tax; amendment of the law with respect to any financial obligations undertaken or to be undertaken by the Government of the Union territory, etc.

Any bill which is not assented by the LG or the President can’t become a law. The veto over legislative assembly is firmly in the Centre’s pocket. Moreover, the Parliament can make any law for the J&K UT and if there is conflict between the Centre’s and UT’s law, it’s the former that will reign supreme.

And until there is no assembly, the LG can promulgate an ordinance which will be implemented as law in the UT.

Suffice to say that the Centre has wide enough powers to set in motion the changes proposed in the article to create megacities out of Jammu and Srinagar. It can also expect cooperation of the regional parties, which if not extended, can be used to deny giving full statehood in future.

Arihant Pawariya is Senior Editor, Swarajya.