Politics

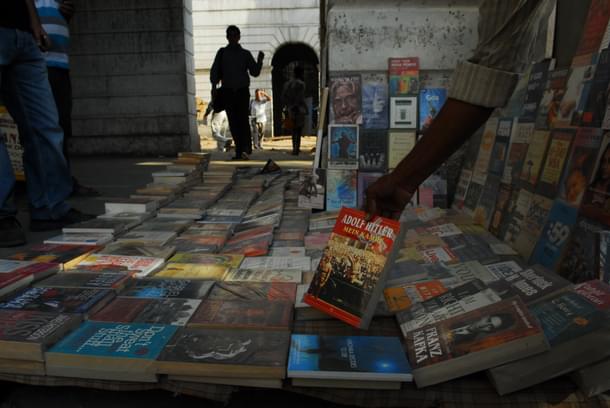

Does The High Sale Of Mein Kampf Suggest Indians Are Jew-Hating Bigots?

Jaideep A Prabhu

Dec 20, 2017, 03:47 PM | Updated 03:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Over the past few years, India has been visited by a slight annual epidemic of a particular kind of imbecility. An article appears in domestic or foreign media with the much trotted-out observation that German dictator Adof Hitler's Mein Kampf remains one of the best-selling books in the country or attention is drawn to a rare cafe or store that bears a name or logo eerily similar to the Nazi regime's emblems. These unsavoury instances are meant to bind the purveyors and their ilk to the horrors of the Nazi regime through associative guilt.

The motivations behind such drivel, especially in a political environment as toxic as India's, are not difficult to fathom and do not merit the dignity of even a contemptuous acknowledgement. However, the decontextualised fondness for Nazi imagery and paraphernalia is ripe for misunderstanding among those who know little of India and its Hindus, the innuendos too tempting for the mischievously motivated to ignore.

The earliest accusations of Nazi sympathies in India came during the Second World War. Subhash Chandra Bose has long been accused of siding with the Axis powers to wage war against Britain. In this, the Bengali leader's inclinations went against those of Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru who reluctantly leaned in favour of their colonial master. Although this has little bearing on the vile accusations today, it is an interesting historical tidbit illustrating the practice and power of defamatory allusions.

Some of the better known examples of reincarnation of the infamous German dictator are a Bombay Cafe in 2006, a Zee TV show that ran 448 episodes from 2011 to 2013, a clothing store in Amdavad in 2012, and an ice cream cone in Uttar Pradesh in 2015. The owners of both the cafe and clothing store pleaded ignorance of the details of Hitler's life when they gained media attention and even an unintended worldwide glare. Complaints were made not only to the businessmen but even to the Indian government – from Israel, Germany, Britain, and the United States – that such names were highly inappropriate in an increasingly global community. Eventually, both men promised to change the names of their businesses.

Such instances are not unique to India – a similar case occurred in Bandung in 2010 where the restaurateur was far less apologetic and stuck to his guns. The restaurant closed in 2013 after the owner received death threats, but reopened a year later as defiant as ever.

Cleaving to the Indian faux pas for the moment, they are harmless incidents whose only actual damage is the crushing boredom from the self-righteous indignation and virtue signalling the cosmopolitan chic inflict upon the public sphere. It is abundantly clear to anyone who looks at these sagas even perfunctorily that an ignorance of history is the key active ingredient. A personal anecdote: while visiting Oswiecim, I met a retired gentleman from Mumbai who had worked for an international airline; he was not sure why his tour guide had brought him to the camp as there was nothing to see. When I explained the Shoah to him in 60 seconds, he could not believe that a civilised nation like Germany could ever be that barbaric and thought I was playing a prank on him!

This is not surprising, given how little emphasis is placed on history in India and how poor the syllabus is even when it is taught. History is rarely taught beyond Class X and even that is mostly a mind-numbing recital of facts that have been ideologically pre-approved. Much of Indian history struggles to be included, let alone international history or any level of detail.

To be fair to Indian history syllabi, the Second World War is about as relevant to contemporary Indians as the invention of the zero was to the discovery of the New World – it is not unimportant but plays a lesser role given the great span of time and intervening events. Western expectations that Indians should know and care about their history smack of hubris especially considering how little world history or geography is known in the West. This is not a defence of ignorance but a reminder of the impossibility of teaching children all of world history in just 10 or 12 years.

Additionally, Asians have, by and large, developed a reputation in the West for being less sensitive to ethnic and religious epithets. This side of Suez that is seen as being direct, plain-spoken, and having a low tolerance of "Western" political correctness. For decades, "Hitler" has come to simply mean very strict in expressions in most Indian languages and nothing more. If anything, such quotidian usage has shorn Nazism of the sort of potency it retains to this day in Europe and the United States: Nazi rallies are a perennial concern in the West, never in India. To judge a foreign culture by one's own standards is nothing but the remnants of an imperial mindset that insists on one's own values being normative.

The innocence of establishments named after Hitler is also apparent to anyone who notices that the entrepreneurs harbour no hostility towards Israel or Jews. What some see as poor taste is usually an attempt to cash in on a meme that is well known but hazy in details. In fact, there is much admiration for Israel among this same "Nazi-loving Hindu-nationalist" demographic that has cheered on Prime Minister Narendra Modi's aim of improving relations with the Jewish state. The only danger to India's Jews actually came from Christian European imperialists rather than even the most zealous Hindus. Jewish history and Israeli politics may not be of interest to many of these "Nazi-supporting Hindus," but they are aware of the frequent headlines that announce Israeli assistance to India in defence, counter-terrorism, agriculture, and a plethora of other fields. The dog-whistle of liking Nazis is nothing more than a vulgar political move aimed at tarnishing potential Hindu consolidation and the supporters of Modi.

What, then, explains the high sales of Mein Kampf? It is nothing more than a deep-seated frustration with the corrupt, incompetent, opaque, and whimsical Indian state. This same, raw emotion is on display when Indians complain that democracy has not served them well. The desire for better services makes many lash out at the present system though these angry words have rarely been followed up by boycotting elections or widespread riots. When expressing their desire for a dictatorship, India's critics of democracy usually add a term limit to the political experiment – India needs a dictatorship for [x] years." Again, this is not an entirely new sentiment – it made for many unexpected supporters of Indira Gandhi's Emergency. After 70 years, Indians seem to be getting increasingly impatient for roads, water, electricity, public transport, and hygiene. Another meme for these basic services is German efficiency, which is what readers of an otherwise boring book are reaching out to. In essence, Indians have separated the aggression and hatred of Nazism from the order it was able to impose on the chaos of interwar Germany.

A thick skin is an essential prerequisite in a globalised world. If Western countries are upset by the fascination of a few Indians – among a billion and a half, almost any number is just a few – with Hitler, they might want to start considering if they are willing to purge their history to suit grievances from the rest. Indians may not be particularly fond of Winston Churchill, for example, and Kenyans, Cypriots, Malays, Indonesians, Arabs, Boers, the Irish and others can surely add to that list. Will the names of these leaders be stricken off buildings and scholarships too? That would be no solution but the question highlights the need for understanding the context of admiration and the unequal impact of certain episodes of history around the world.

Jaideep A. Prabhu is a specialist in foreign and nuclear policy; he also pokes his nose in energy and defence related matters.