Politics

Emergency: When Power Wreaked Havoc And How

Book Excerpts

Jul 17, 2017, 04:24 PM | Updated 04:24 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

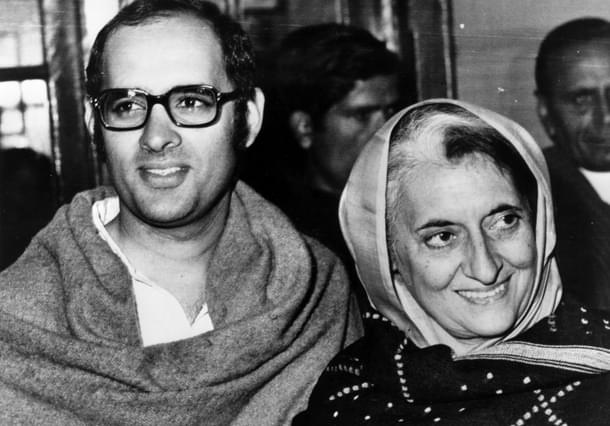

Even before the nation could complete three decades as an Independent nation having fought the colonisers to be a ‘sovereign democratic republic, the one at the helm of affairs decided to give the nation a taste of tyranny yet again. Indira Gandhi, the country’s third and till-date only woman Prime Minister had emergency declared across the nation enabling her to rule by decree, absolutely unabashed, unapologetic and unruly. Author A Surya Prakash’s book The Emergency, Indian Democracy’s Darkest Hour narrates the tale of how every pillar of democracy was reduced to a rumble.

Here is an excerpt:

In other words, it was not the Prime Minister’s Office or the Government of India which was calling the shots and taking decisions. It was a coterie around Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi and it was the prime minister’s household that had taken charge of the nation’s affairs.

Probably there was just one individual in the Prime Minister’s Office – P. N. Dhar, secretary to the prime minister – who knew what was happening some hours before Mrs Gandhi’s Cabinet colleagues. He got to know when he was summoned at 11.30 p.m. on 25 June to Mrs Gandhi’s residence to take a look at the speech that she was to deliver the next morning on All India Radio. He was to go through the draft that Ray, Barooah and Indira Gandhi had put together. The Shah Commission concluded on the basis of evidence that came before it that the most important functionaries in the government did not know anything about the proclamation of Emergency till very late or learnt about it only on the morning of 26 June.

‘Deteriorating Law and Order’ – Indira’s Blatant Lie

Some people had a premonition that politics in India would undergo drastic change. Among them was B.N. Tandon. His diary entry on 31 December 1974 was revealing:

“Today this year comes to a close. It is natural to wish the best for the new year. But I am filled with foreboding. Gradually, a crisis is building up which, if there is no improvement in the situation, will overwhelm the government. The truth is that her domination has increased massively and is still increasing. JP and Morarji may be wrong about many things but they are right when they say that a cloud of fascism and dictatorship is hovering over the country. Their warnings are not misplaced.’

‘… the prime minister will not flinch from anything to maintain herself in power. This could prove a big danger to our democracy. Individual liberties can be quashed. The new year is emerging on the horizon of time with gravest apprehensions.’ Veteran Congress leader Margaret Alva, in her autobiography, also endorses this view.

‘However, despite Indiraji’s assertions to the contrary, the general perception was the Emergency had been declared more to save a chair than a nation. There was an immediate backlash. Those who had hailed Indiraji as ‘Durga’ in parliament, and had glorified her after the Bangladesh war, turned into severe critics and foes.’

Indira Gandhi’s oft-repeated claim that the law and order situation in the country had deteriorated and that this warranted the imposition of Emergency remained unsubstantiated by facts.

Actually, it turned out to be a blatant lie. The Shah Commission exposed her falsehood fully. It found that official records were telling a different story. It examined the fortnightly reports sent by the governors in the states to the president and by the chief secretaries of states to the Union home secretary. These reports indicated that the law and order situation was ‘under complete control’ all over the country. In the weeks and months preceding the Emergency, the home ministry had not received any reports which said that the situation had deteriorated. The claim that things had deteriorated on the economic front were also without basis. There was nothing alarming on the economic front. The Shah Commission found that the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) had declined by 7.4 per cent between 3 December 1974 and the last week of March 1975 as per the Economic Survey for the fiscal year 1975-76 which was prepared by the very same government.

Even more interestingly, the Intelligence Bureau, which is supposedly the eyes and ears of the government and which often acts as an advance warning system and tips off the Union government about impending political storms and civil strife or workers agitations, had not submitted any report to the government between 12 and 25 June 1975 saying that the law and order situation was getting out of control. Further, the home ministry, which is the nodal ministry for internal security, had not sent any report to the prime minister saying that things were getting out of hand. And, indicative of how Mrs Gandhi’s government treated this ministry was the fact that it did not have a copy of the communication sent by the prime minister to the president recommending imposition of Emergency.

How the Tail Was Wagging the Dog

Thus, there was this extraordinary situation where in the cabinet secretary, the home secretary and the secretary to the prime minister had not been taken into confidence on such a critical decision. But, R. K. Dhawan, additional private secretary to the prime minister, played a key role in making preparations for imposing the Emergency – drawing up lists of persons to be arrested, for promulgation of the Emergency (recall how he took Indira Gandhi’s letter to Rashtrapati Bhavan and obtained the president’s signature on the dotted line at 11.30 p.m. and even the president’s secretary was kept in the dark that night on the contents of that communication), and for orchestrating the events the next morning.

Similarly, Om Mehta, the minister of state for home affairs, was a confidant of Indira Gandhi and her coterie, but Home Minister Brahmananda Reddy was not. The latter was summoned late that night only to sign a quickly drafted letter to the president. This was true of the governors and chief ministers as well.

The lieutenant governor of Delhi was special. He knew a lot of what was happening, but no other governor did. The chief ministers of Haryana, Punjab, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal had advance intimation of what was coming. But the governments of Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Jammu and Kashmir, Tripura, Orissa, Kerala, Meghalaya and other Union territories were not so lucky. H. N. Bahuguna was the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, the biggest state in the country. What he told the Shah Commission was interesting. He learnt about the Emergency on the morning of 26 June when he was having breakfast with two Union ministers – Uma Shankar Dikshit and K. D. Malaviya, ‘and they were as surprised as he was about the promulgation of Emergency’!

Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi had a list of their chosen confidants – they could be ministers, chief ministers, low-level officials or just minions and mere cogs in the government wheel. Their status in the pecking order did not matter at all. The cabinet secretary did not matter, nor did the secretary to the prime minister. But R. K. Dhawan, a minion in the prime minister’s household, mattered a lot. Similarly, no governor of any state was to be consulted, but Krishan Chand, the lieutenant governor of Delhi, who was virtually hanging around Indira Gandhi’s household, could be trusted. Krishan Chand was okay, but he was not all that important. Navin Chawla, a mere secretary to the lieutenant governor of Delhi, was more important than him.

Often, it was a case of the tail wagging the dog, but the dog was helpless. It could neither bark nor bite. It was condemned to suffer in silence and wait for the day the prime minister would commit a mistake which would enable the dog to have its day!