Politics

How To Think About Telangana Elections

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Nov 29, 2023, 06:52 PM | Updated 06:59 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Campaigning for the Telangana assembly elections has ended. Now only the voting remains. To understand what the ballot box might say, and why, we must merge both the electoral and census data.

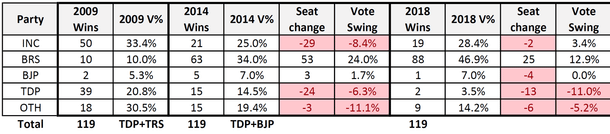

A bare-bones reading of past assembly election results would rightly lead to the inference that K Chandrashekhar Rao (KCR) and his BRS rose to gain power by first attracting votes from the very TDP of N Chandrababu Naidu whom he allied with in 2009, and then from the Congress after Jaganmohan Reddy had a fractious falling out with that party.

In the process, the BRS won in 2014, and then again in 2018, improving its position each time. KCR has been Chief Minister for nearly a decade now. As things stand, and if the pollsters are right, the BRS should win again in 2023, the Congress may enjoy a mild resurgence (albeit not to the extent that it can garner a simple majority), and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would remain a distant third.

But that political history of Telangana is a simplistic one, because, in fact, that state’s politics is a lot more nuanced many perceive. And that in turn is a function of the state’s demographic distributions.

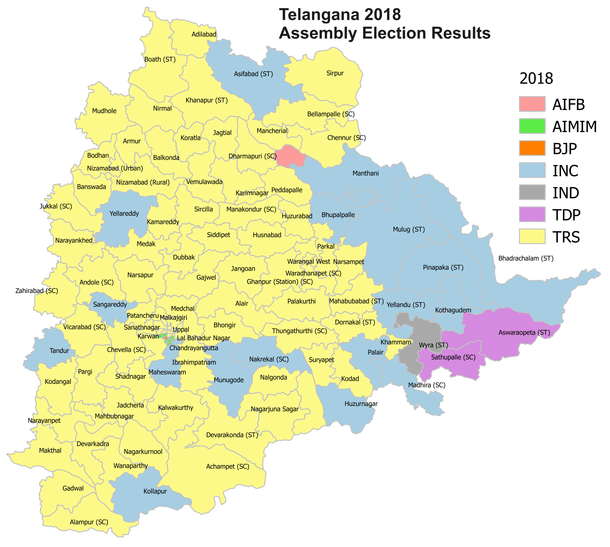

Muslims constitute only 13 per cent of the population, but they are concentrated in the city of Hyderabad, and four north-western districts – Medak, Nizamabad, Ranga Reddy, and Adilabad. For ages, they were stout Congress supporters in the districts, until the majority shifted allegiance first to the TDP, and then, after the TDP aligned with the BJP, to the BRS.

This is where the BJP has started performing moderately better in the past decade (Secunderabad is an urban outlier which became a BJP bastion decades ago).

Scheduled castes form 15 per cent of the population, and are almost evenly distributed across Telangana. Anecdotal evidence indicates that some segments have converted to Christianity, but quantification is difficult, since nondisclosure permits people to avail of reservations and government schemes.

Scheduled tribes make up 9 per cent, and are concentrated in two areas – Adilabad in the north, and in the eastern districts of Khammam, Warangal and Nalgonda. Their support has traditionally been more for the Congress. It is a segment which the BJP has yet to make inroads into, and one of the reasons could be covert conversions (which is pretty much the unwritten form in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh). So, we see that about 40 per cent of the electorate is susceptible to identity politics.

Surveys indicate that over a third of the population belong to the backward classes (OBC). But, no one OBC community is numerically dominant. Instead, it is subdivided into over a dozen groups, each of whom range from between 1-6 per cent of the total population.

On the other hand, the balance one third are categorized as forward castes (FC). The Kapu community is the largest FC group with 15 per cent (roughly equal to Scheduled Castes, and slightly more than Muslims). They are followed in descending order by Reddys, Kammas, Velamas, Vysyas (Bania), Kshatriyas, and Brahmins.

A number of prominent leaders and Chief Ministers belong to the FC category. KCR is a Velama. NT Rama Rao and N Chandrababu Naidu are Kammas. Chiranjeevi and Pawan Kalyan are Kapus. G Kishen Reddy of the BJP, who represents Secunderabad constituency in parliament, is also an FC.

This is what makes Telangana politics interesting and unique. For example, although NT Rama Rao earned the ire of the OBC community when he abolished the Patel-Patwari land tenurial system in the early 1980s, he was able to weather that storm by allying with communities from the other 40 per cent. So too, Chandrababu Naidu, who had a good thing going until the Muslim vote deserted him.

Only an astute politician can stitch together a successful, durable coalition of such diverse communities, across a state with such varied demographics, under a single party’s banner.

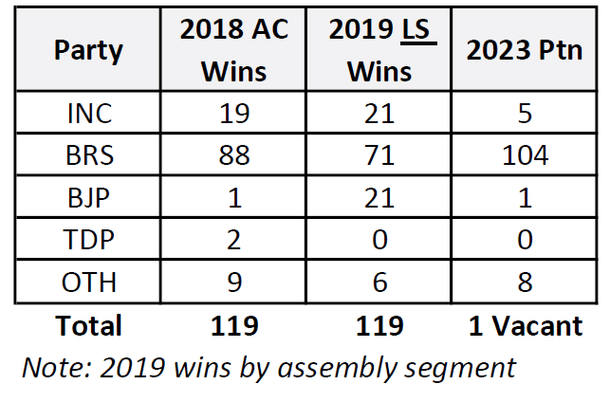

This is the mountain the BJP has to climb. They did very well in northwest Telangana in the 2019 general elections, polling 20 per cent. That is up 13 per cent from what they got in the assembly elections of December 2018. The won four seats, and, in a major upset, KCR’s daughter K Kavitha lost poorly to Arvind Dharmapuri of the BJP in Nizamabad.

KCR’s response by way of damage control was to whittle away at the Congress, and reduce the latter’s position to tatters in the legislature. A table below says it all:

Thus, we see that the Congress ‘resurgence’ referred to frequently in the media, is actually nothing more than a recovery of sorts from a dreadful position. The party may still do moderately well, but it will be extremely difficult for them to dislodge KCR and the BRS.

Indeed, in conclusion, the most intriguing aspect of the Telangana assembly elections will, in fact, be to see how much of the 2019 vote share the BJP retains in 2023; because, if the BJP crosses into double digits, it will lead to a number of unpredictable three-way contests.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.