Politics

In Maps: An Electoral History Of Karnataka

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Apr 15, 2023, 06:28 PM | Updated 06:28 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

As Karnataka prepares for another exciting assembly election, Swarajya invites its readers on a cartographic walk through the state’s electoral history.

It’s been 67 years since the first provincial elections were conducted in Karnataka. In that time, the boundaries of the state and its constituencies have changed, and it has become an industrial powerhouse, while political parties emerged, grew, split, thrived, or were voted out into oblivion.

However, a few common strands have persisted along this arc.

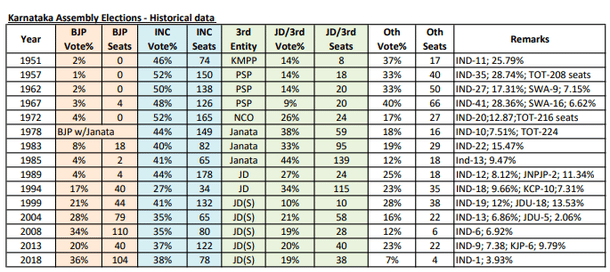

As a table below shows, the state was overwhelmingly dominated by the Congress party for the first three decades after independence. While the party’s prominence has diminished post-1983, it still commands the largest vote share in the Vidhana Soudha.

A second strand is the sustained presence of a socialist, non-Congress-non-Hindutva vote base, which managed to seize the popular mandate a few times.

Between the 1950s and the 70s, this strand was represented by the Praja Socialist Party.

Since the Emergency, the position has been taken over by the Janata Party and its derivatives, with the current one being the Janata Dal (Secular), the JD(S).

A third strand is the influence which independent candidates have wielded in the state over the past seven decades.

Whether as rebels, or as genuine local luminaries who could hold their own against established parties, independents had always attracted a sizeable chunk of the votes until as recently as 2004, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) commenced its ascendant march.

But curiously, the BJP (and its earlier avatar, the Jana Sangh) had to struggle till 1999 before they were able to cement their place in Karnataka.

They had done moderately well twice before, but as we shall see, both were temporary successes gained on the political woes of others, and not a widespread, grassroots, cadre-based win.

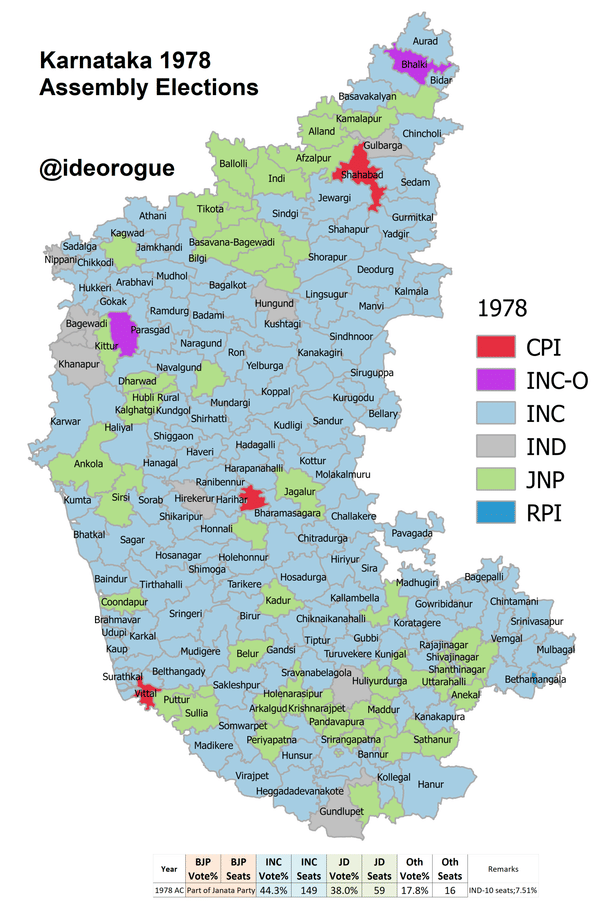

We commence our peregrination with the assembly elections of 1978.

To everyone’s surprise, Indira Gandhi’s Congress, state party leader Devraj Urs, and the electorate, swam against the tide for the second time in as many years, to hand the Congress a thumping win.

The party was wiped out in the north, in the general elections of 1977, and survived only because of its successes in the south (a region less affected by the travesties of the Emergency).

Unfortunately, Urs had a falling out with Indira Gandhi, left the party, tried to split it, failed, and was replaced by Gundu Rao, whose administration swiftly became mired in a sordid saga of corruption.

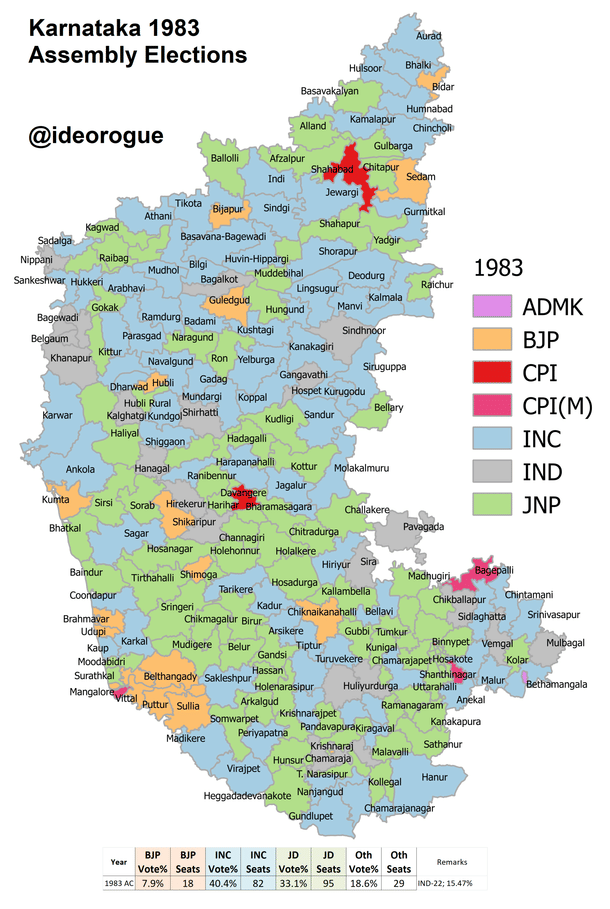

Rao was promptly voted out in 1983, and Ramakrishna Hegde of the Janata Party formed a coalition government in alliance with the BJP and others.

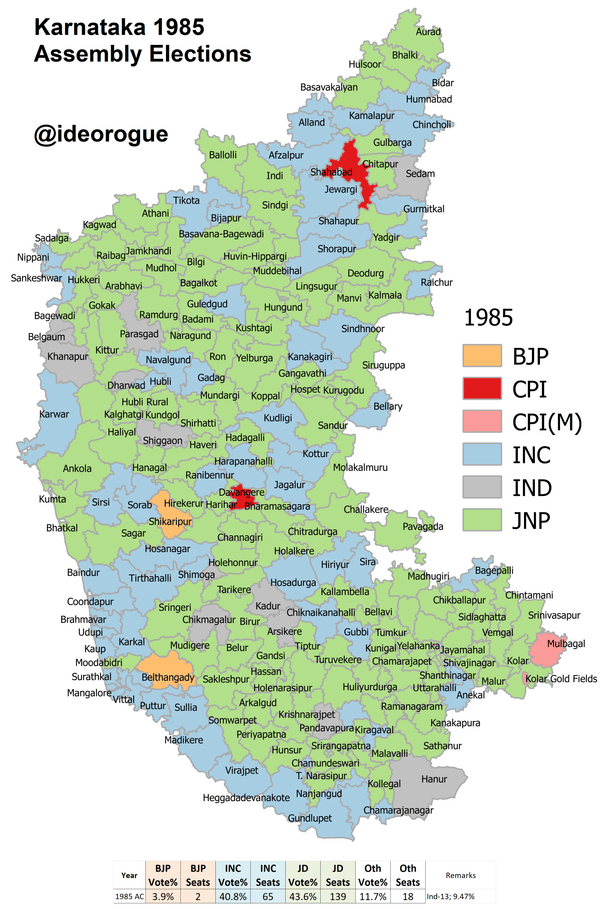

But Hegde chafed at having to be dependent on the BJP, and so he called mid-term elections in 1985.

It was an audacious move, since the Congress under Rajiv Gandhi had just swept the entire country to an extent never seen before or since.

But it worked, the BJP was wiped out, and Hegde’s Janata Party won 139 of 216 seats.

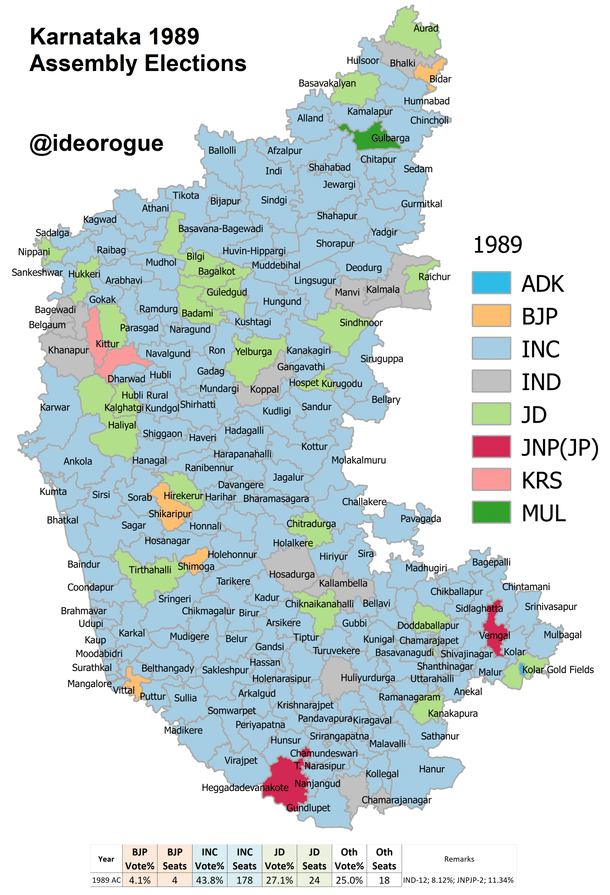

In 1989, though, it was the Congress’s turn to buck the trend, by winning in Karnataka even as Rajiv Gandhi’s mandate was burnt to a crisp by the Bofors scandal.

But 1989-1994 was an unhappy term for the Congress, which saw the Chief Minister being changed twice.

Veerendra Patil was forced to go after he rebelled against the party’s central leadership. There was a spell of Presidet’s Rule before S. Bangarappa was appointed, and then he was replaced after two years by Veerappa Moily.

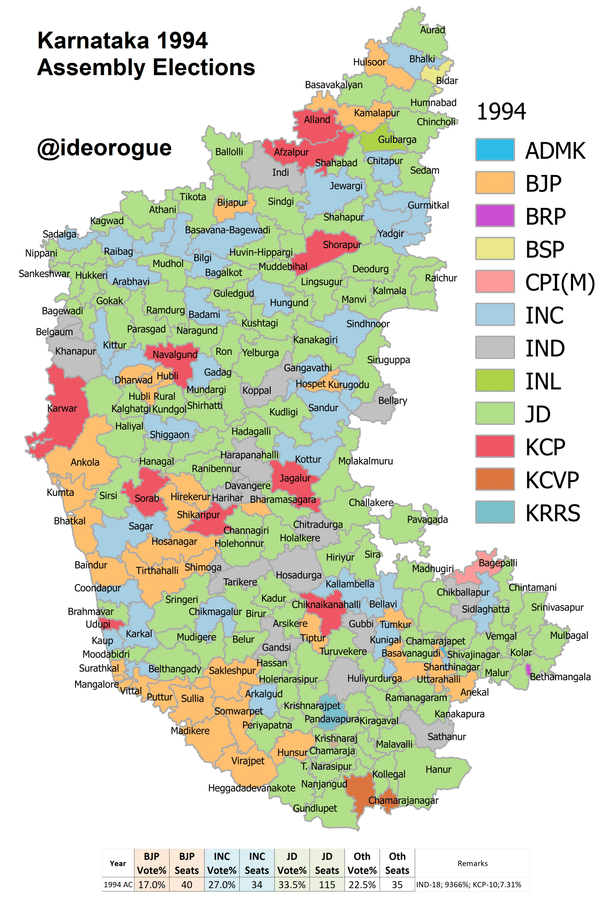

Having had enough of these musical chairs, the Kannadigas gifted the 1994 mandate to Deve Gowda of the Janata Dal. This is also when the BJP made its first real splash, winning 40 seats with 17 per cent of the popular vote.

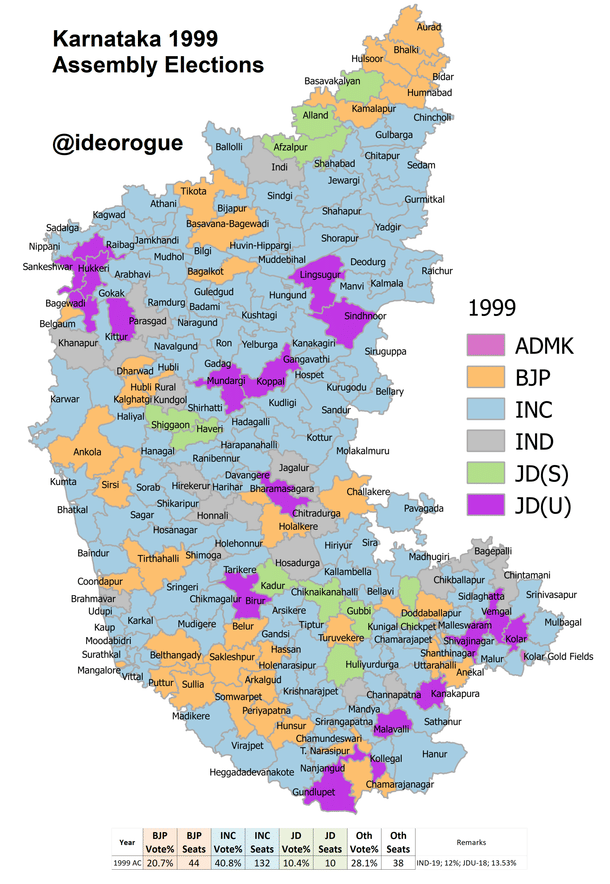

The Janata Dal’s provincial mandate, and cadre discipline, was weakened when Deve Gowda became Prime Minister in 1996, so it expectedly split. This was precisely the opening the Congress needed, to force a return in 1999 under SM Krishna, and in the melee, the BJP stagnated.

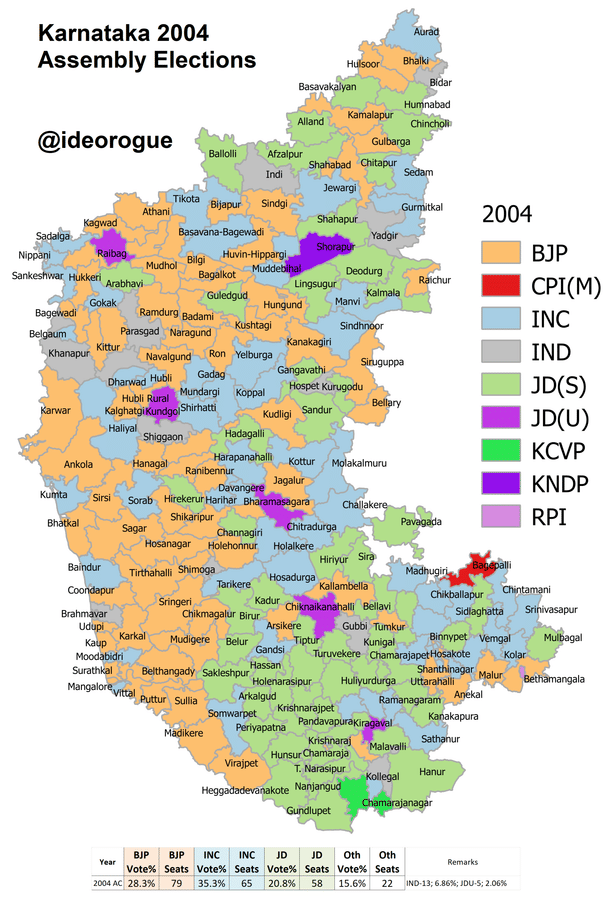

By 2004, the state’s dynamics began to settle into the trend we see today.

The BJP was now firmly on a growth path, the JD(S) never really recovered from the split of 1999, to become largely restricted to the Mysore region, and the Congress remained as the only party with a pan-state presence.

As a result, the vote was cut three ways, and the 2004 results threw up a hung assembly. Karnataka saw three Chief Ministers from three parties in this term.

Dharam Singh of the Congress held the post for under two years, before vacating it for Deve Gowda’s son, HD Kumaraswamy for a similar term.

But in this scramble for power, the Congress-JD(S) equation soured, there was a brief term of President’s Rule, followed by a futile week-long effort by BS Yediyurappa of the BJP, followed by one more period of President’s rule, before the house was finally dissolved.

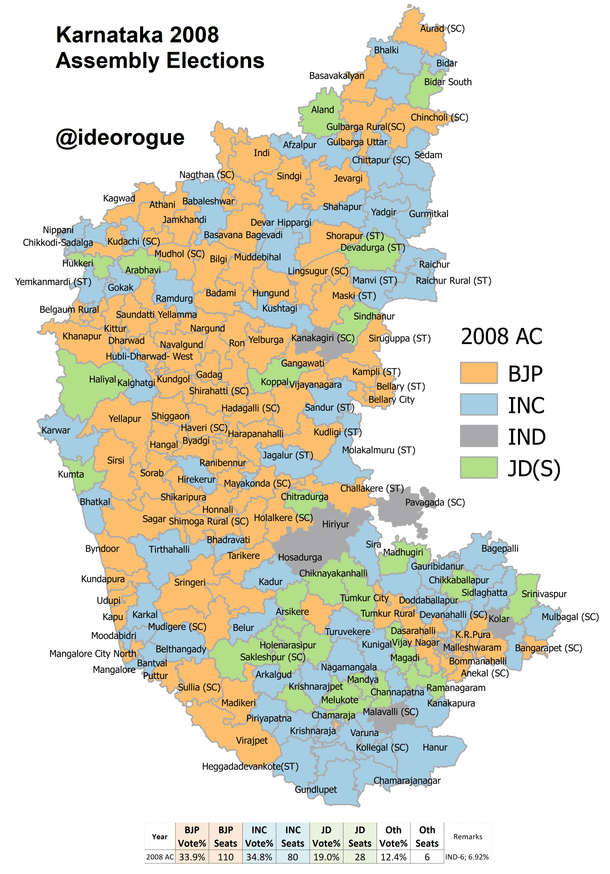

The elections of 2008 were the BJP’s to sweep, yet they fell agonizingly short of the majority mark by merely three seats, because they were unable to make inroads into Southern Karnataka.

Nonetheless, Yediyurappa managed to cobble together the extra seats to form a functional BJP government for the first time in the state.

But like in Gujarat a decade before, success was the party’s undoing. Yediyurappa was replaced by Sadananda Gowda after three years, and Gowda by Jagdish Shettar for the last year of this term.

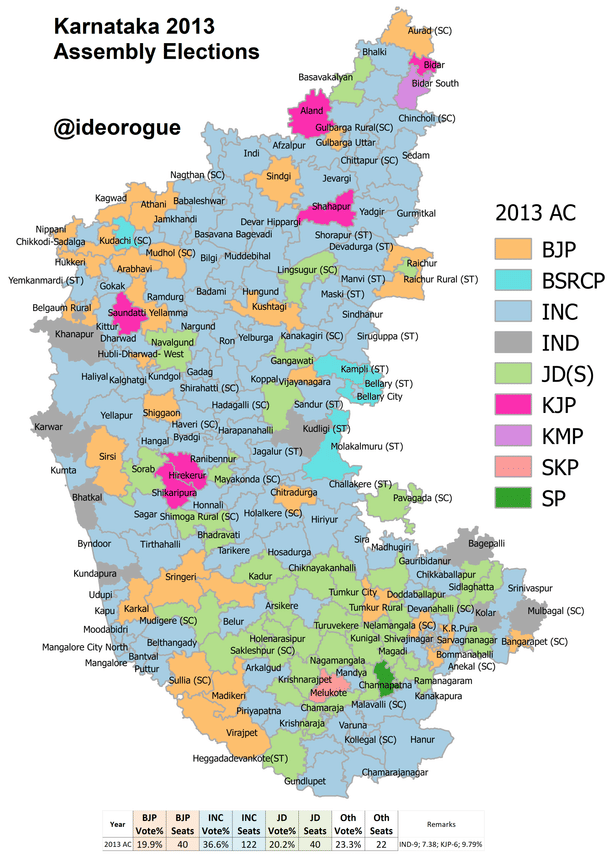

Yediyurappa’s reaction to his side-lining was explosive: he quit the BJP, started his own party, and decimated the BJP in the elections of 2013.

It set the party’s growth in the state back by a decade, and handed the popular mandate on a saffron platter to Siddaramaiah of the Congress.

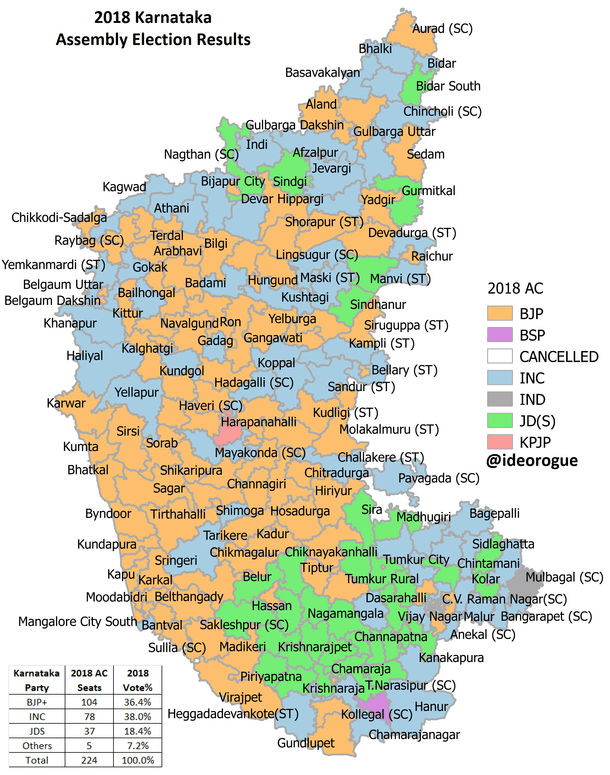

By 2018, though, the BJP under Narendra Modi managed to bring Yediyurappa back into the party, and undertake the laborious task of repairing the damage caused by the rebellion of 2013.

Unfortunately, while the BJP tended to its injuries, it was unable to revert to the growth path of 1999-2008.

As a result, the 2018 threw up another hung assembly, with the BJP slightly short of the halfway mark.

Once again, Yediyurappa tried to prove his majority, but he failed within a week and had to make way for a Congress-JD(S) coalition led by HD Kumaraswamy.

Hardly anyone expected Kumaraswamy to head his coalition for five years without incident, but everyone was caught on the wrong foot by what happened next.

In July 2019, soon after the general elections in which the BJP swept Karnataka, the party engineered a dozen-odd defections, mainly from the Congress, and some from the JD(S), to reduce the Kumaraswamy government to a minority.

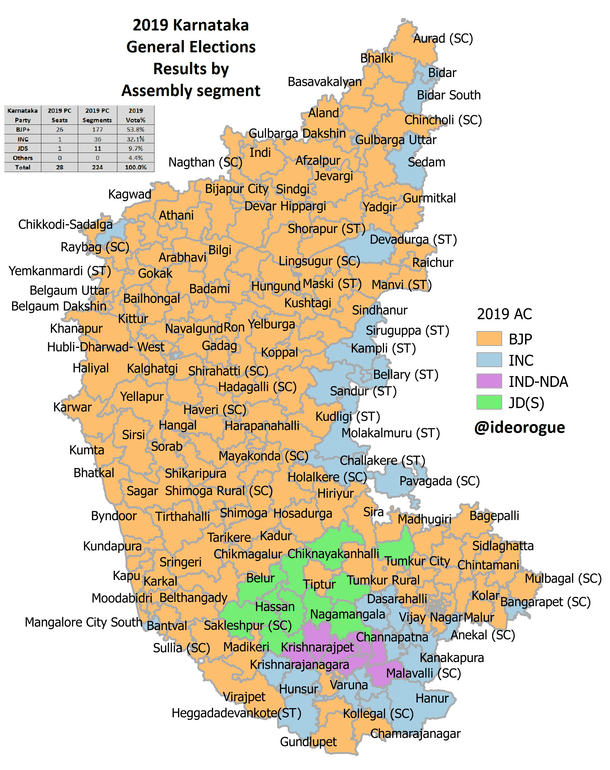

The BJP’s confidence that they could pull this off was a direct function of their excellent performance in the 2019 general elections.

Not only did they sweep the north and the centre, but they also made strong inroads into the south for the very first time.

A map of the results at the assembly segment level says it all.

So, this is the whirling vortex which constitutes Karnataka politics. It is tough, bruising, with no quarters given, and they don’t take prisoners.

If the Congress’s Siddaramaiah or DK Shivkumar give back as good as they get, or Kumaraswamy and his JD(S) bend over backwards like Mongolian acrobats, to appease their precious Muslim vote bank, then the BJP are no angels either.

But there is a difference in 2023: the independents are no longer a force in the state, the JD(S) is going to lose many of its pockets of influence in the northern and central parts (largely to the Congress), the BJP will do much better in the south, and the Congress is riven by internal rivalries. Thus, this assembly election is, rather like 2008 was, the BJP’s to lose.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.