Politics

Madhya Pradesh 2004-2009: Symbol Of A Fumbling, Confused BJP Of The Era

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Mar 14, 2024, 05:43 PM | Updated Mar 15, 2024, 03:22 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

“And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” — W B Yeats, The Second Coming, January 1919

The buzz on the street during the run-up to the 1989 general elections was about the advent of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Pollsters and commentators were sure that the BJP would announce their arrival in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, do reasonably well in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi and Rajasthan, and majestically sweep Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh (MP).

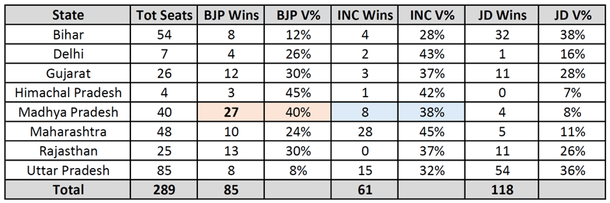

In the end, that is exactly what happened; the BJP won 85 seats in alliance with the Janata Dal of V P Singh.

And Rajiv Gandhi, embattled by grave charges of corruption and rank minority appeasement, had to bear the triple ignominy of losing his title of ‘Mr Clean’, watch his arch nemesis V P Singh walk away with the mandate, and suffer the beginning of the end of his party in large state after state, for reasons of his own sordid making.

As a table below shows, the electoral carnage of 1989 was so devastating that the Congress has actually never recovered from it till date.

The BJP’s standout performance, as expected, was in MP; with 27 wins and 40 per cent of the vote, it was the first large state where the party bested the Congress on both key electoral metrics.

Among the BJP’s winners was a young, firebrand orator named Uma Bharti, then only 30 years old, who won from Khajuraho in MP with a staggering 61 per cent of the popular vote. Her victory margin was greater than her veteran Congress opponent’s vote share — Vidyavati Chaturvedi, who won in 1980, and again in 1984, defeating Bharti.

From then on, for the next 15 years, the BJP’s performance in MP was one of the key yardsticks for how it fared nationally (barring 1991, which a transition election in which a large portion of the Janata Dal vote went back to the Congress).

Even in the 2004 general elections, when the BJP suffered an unexpected defeat, it did exceptionally well in MP; it won 25 of 29 seats with a record 48 per cent vote share. That was the most seats from any state, of the 138 it won in total.

These numbers were made even more emphatic by that fact that the BJP had just swept the state in style under the leadership of Bharti, winning 173 out of 230 seats in the assembly elections of November 2003. It was a unique moment.

Not only did MP get its first woman chief minister, but it was also the first (and only) time in modern Indian history that a saffron-clad sanyasin became the chief minister of a state.

The best talents of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) contributed to both the assembly elections of late 2003, and those of May 2004; veteran worker Kaptan Singh Solanki managed the war room in Bhopal, while Arun Jaitley managed the media with able assistance from Amitabh Sinha.

Party veterans and former chief ministers like Kailash Joshi and Sundarlal Patwa may not have fully digested the forceful advent of Bharti, but they were both mature and disciplined enough to gracefully accept the generational leadership change being wrought.

Prima facie, one would not have been mistaken in thinking that the civilisational vote had finally been awakened in MP. But it was not to be; within months, things fell apart, the BJP’s centre failed to hold, and in veritable Yeats-ian fashion, vexed the party’s cradle to nightmare for a woeful decade.

When the BJP lost the general elections of 2004, Lal Kishan Advani replaced Venkaiah Naidu as party president. For those who believed that the loss was a result of the BJP straying from its ideological roots, albeit for compulsions of ‘coalition dharma’, Advani’s return to the helm would have presaged the return of Hindutva to the vanguard.

It was an era when prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee openly admitted in Parliament that their key issues, like Ayodhya or a uniform civil code, would have to be placed on the backburner since they simply hadn’t the mandate to see them through.

But for people like Bharti, who had just engineered a stellar victory in MP without having to compromise on their ideology, this was pragmatism being taken to extremes without suitable returns. So, they chafed; some silently, others openly.

The rupture came in August 2004, when Bharti was forced to resign after a police case was filed against her in Karnataka, for the Hubli Idgah riots of a decade before. To her surprise, rather than supporting her, powerful lobbies were only too glad to see her go. Her replacement was Babulal Gaur.

If being let down wasn’t bad enough, whisper campaigns sprang up against Bharti.

Who started it is unknown, but we can well surmise that the culprits were a tiresome melange of the disaffected and the disenchanted; those who had tied their careers to the coattails of Patwa or Joshi, and, lacking merit, now found themselves side-lined; or those who couldn’t digest the fact that a woman, and that too, one from the Other Backward Class, had swept MP with her spunky drive.

Things came to a head in Delhi, in November 2004, when Bharti had a very public spat with Advani, following which, she stormed out of the meeting. The media reported that gleeful supporters of Gaur openly distributed sweets when this news reached Bhopal.

Why didn’t the central leadership support her? Was it because they were unable to rein in the various factions, or is it because, after having gotten accustomed to running a coalition government for six years, the likes of Bharti had become too BJP for the BJP?

The chief minister of Gujarat at that time, who had been meted similar treatment, might have pointed to the latter reason if he was inclined to comment.

Yet, the question is moot because within six months, Advani was forced to resign as the president of the BJP, after he disastrously praised Jinnah during a visit to Karachi; and Gaur was replaced by Shivraj Singh Chauhan in November 2005.

But the party’s problems didn’t end there. In mid-2006, a livid Bharti floated her own political party. It would have been curtains for the BJP in the assembly elections of 2008, but for the fact that the Bahujan Samaj Party and motley independents cut into the Congress vote.

So, even if Bharti’s party contested 201 seats, won five seats, and polled 5 per cent, the BJP still managed to win 143, albeit with a significantly reduced vote share.

But that luck didn’t extend into the 2009 general elections; from 25 wins out of 29 in 2004, the BJP’s tally in MP dropped to 16 in 2009, and to just 116 seats nationally. The BJP had denied itself the popular mandate once again.

Mercifully, that was the BJP’s low point, both in MP, and at the national level. The RSS drew a line, Bharti was welcomed back into the fold in 2011, put in charge of reviving the party in Uttar Pradesh, and tasked with consolidating the vote base.

By the end of 2012, Narendra Modi had won his third term in Gujarat, and preparations were on, to propel him to Delhi. The rest, as they say, is history.

Looking back, we see that Bharti was no stormy petrel. Rather, her rebellion was a symptom of a broader malaise, and the BJP paid a heavy price in the 2009 general elections because it lacked the collective conviction to accept that truth, and act accordingly.

It is also a good lesson for the future: creeping complacency combined with risk aversion invariably leads to disaster.

(This article is the second of a series which surveys the performance of the BJP in the general elections of 2004 and 2009)

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.