Politics

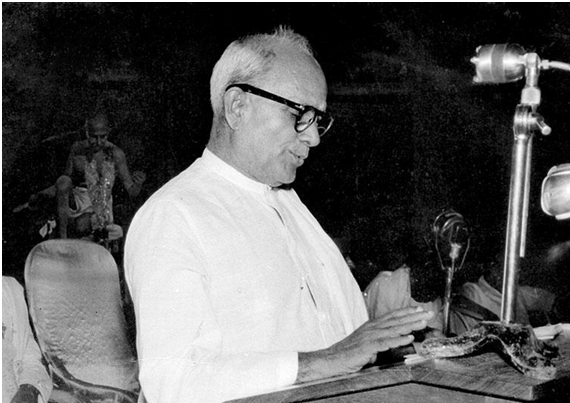

Mannathu Padmanabhan: Remembering A Reformist Amidst The Sabarimala Turmoil

Ananth Krishna

Jan 02, 2019, 04:38 PM | Updated 04:37 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court recently allowed the entry of women between the age group of 10 and 50 into the Sabarimala temple, and since then the political situation in Kerala has been turbulent, to say the least. The Nair Service Society (NSS), a social welfare organisation of the Nair community, has been at the forefront of the agitation against the implementation of the judgement. The NSS was represented by renowned lawyer K Parasaran during the hearing on the public interest litigation (PIL), and had mounted a strong defence of the traditions of the temple.

Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, general secretary of Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M) has been pursuing the NSS consistently, urging it to change its stance. The primary reason behind the insistence of the CPI(M) to get the NSS on its side is because the founder of the organisation, Mannathu Padmanabhan, was a leading figure in Kerala’s reformist movement in the early twentieth century.

Balakrishnan, who incidentally hails from the Nair community, has argued that the NSS is not following the “reformist ideals” of Padmanabhan. The NSS has hit back at Balakrishnan saying that the organisation was well aware of Padmanabhan’s views and principles. The Sabarimala episode has now again put the focus back on the historical legacy of Padmanabhan. With his 141st birth anniversary being celebrated today (2 January), it would be pertinent to look at his accomplishments, which might not be as well-known as that of his contemporaries.

Born in 1878, Padmanabhan started his career as a school teacher, but later became a lawyer in 1903. Realising the imminent need for reform and the upliftment of the Nair community, he formed the NSS in 1914. His stated aim was to change the feudalistic mindset of Nairs along with the traditional matrilineal system (Marumakathayam) that was being followed, which Padmanabhan considered to be a barrier to the social upliftment and economic welfare of the community.

He believed that Marumakathayam had resulted in increasing conflict in the family and community due to property disputes. While organisations such as the Malayali Sabha and Keralaya Nayar Samajam had been active in the years prior, they still had limited reach and appeal. Under Padmanabhan’s leadership, and with the help of his exemplary organisational skills, the NSS was able to consolidate and organise the various Nair sub-castes. Along with the social upliftment of the community, the NSS wanted to ensure educational progress and autonomy. The NSS had in its formative years been led by K Kelappan, known as ‘Kerala Gandhi” as its founding president, who along with Padmanabhan played an important role in the development of the organisation.

Padmanabhan And The Temple Entry Movement

Recognising the social ills that were prevalent in the Hindu society in Kerala, Padmanabhan and the NSS rose to the task at hand. Padmanabhan himself sat for a meal with a man from a Pulaya community in a bid to dispel untouchability.

In 1924, Padmanabhan played a significant role in the Vaikom Satyagraha, which was started by the Ezhava community who were considered avarnas. The satyagraha supported by Sree Narayana Guru was against the prohibition imposed on avarnas on entering temple and surroundings.

The Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee (KPCC) formed the Untouchability Action Committee (UAC) which gave nominal leadership to the agitation. The satyagrahis were selected from all the Hindu communities. Padmanabhan led a savarnajatha (procession) from Vaikom to Thiruvananthapuram, to show the pan-Hindu support the agitation had aroused.

The group led by Padmanabhan swelled from 500 at the beginning to 5,000 when it reached Thiruvananthapuram on 12 November 1924. The jatha along with the NSS had collected 25,000 signatures and called upon the Maharani Sethu Lakshmi Bayi to open the roads to the temple and other locations without distinction of caste or creed. At this point, Padmanabhan was convinced about the cause of temple entry for Hindus of all castes, and he threw open his own family temple to all Hindus.

He took up the cause of temple entry in a big way, and the NSS karayogams (local committees) across the state passed resolutions in favour of temple entry. In 1932, the Guruvayur Satyagraha was organised, when K Kelappan undertook a satyagraha for 12 days for the entry of untouchables into the Sree Krishna Temple. As in Vaikom, the Guruvayur Satyagraha too eventually met with success. The role played by Padmanabhan and the NSS was absolutely crucial in countervailing the prevailing orthodox opinion among upper caste Hindus.

Collaborating with the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP), the NSS organised many grassroots meetings to promote the cause. The sustained efforts of the reformers eventually bore fruit and the Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936 was issued by Maharaja Chithira Thirunal Varma, which opened all temples in the erstwhile Travancore Kingdom to all Hindus. Padmanabhan’s understanding of the necessity of Hindu unity for social progress still guides the actions of the NSS today, with every member swearing to work tirelessly for the progress of the Nair community, but not through any activity that weakens any other community.

Reforming The Nair Community

The NSS and Padmanabhan aimed to bring about substantial reform in the Nair community. These efforts led to the Nair Regulation Act of 1925 for the equal sharing of property among members of the same family. This was made in an attempt to reform the Marumakathayam system that had fallen into dysfunction. The act also prohibited polygamy and prohibited the marriage of girls less than 16 years of age. This was also replicated in Kochi in 1938.

Post-Independence, Padmanabhan emphasised on educational progress, and established many institutes for higher education. After the formation of the Kerala state on 1 November 1956, and the subsequent election of a communist government, the NSS actively opposed the Education Bill that had been proposed by the state government. Padmanabhan led the vimochana samaram (liberation struggle) against the move of the communist government to reduce the autonomy of educational institutions. He was also the first president of the Travancore Devaswom Board, and in this position attempted to revitalise many temples.

The then president of India bestowed the title of Bharatha Kesari on Padmanabhan in 1959 and he was further honoured by the nation in 1964, when he was awarded the Padma Bhushan. Padmanabhan’s contributions to the progress and revitalisation of the Nair community are unparalleled. He stands among the titans of Kerala’s social reform movement, but his legacy has not taken the same roots as his erstwhile peers.

Ananth Krishna is a lawyer and observer of Kerala's politics.