Politics

The Great Indian Drought Circus

Praveen Patil

Oct 09, 2015, 06:32 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 08:58 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

If the Modi-led government liberates India from regular drought, it would be a colossal achievement for which the nation will thank it.

Last week, scores of women belonging to various Kapilavastu villages of Siddhartha Nagar district of eastern Uttar Pradesh went into Aligarwa police station carrying buckets of water with them. They had an unusual request to make of the thana in charge, SHO Ranvijay Singh. They wanted to bathe the police inspector in public with buckets of water they were carrying!

Bathing the local Raja in public to invoke the rain Gods during extreme drought years is an old tradition here. Since there are no kings in modern-day democracies, desperate villagers had turned to the local Police Inspector as their last hope to survive another rainless year.

This is indeed the 21st century India, a nation of smartphones and Facebook and WhatsApp and Flipkart. This is an India staring at a second successive year of drought where most villagers are virtually hanging by a thread and have nothing to fall back on but some ancient, meaningless rituals that stand as little chance of bringing rains as an evangelist who promises ‘second coming’.

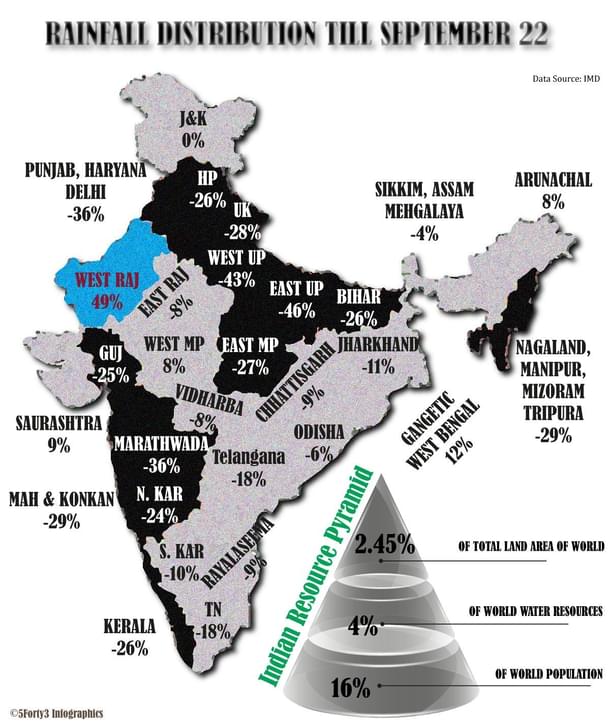

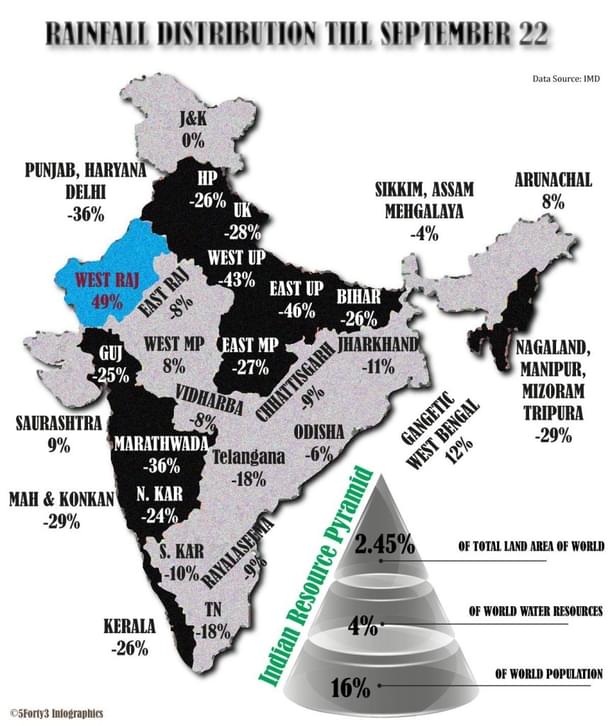

India, which accounts for 16% of the world population, only has 4% of the global water resources so our dependence on rain is quite natural, but what is dismaying really is the overdependence on rain despite having suffered humungous losses in the past. This year, once again we are witnessing more of the same.

Nearly half of the 670 odd districts of India are suffering from drought-like conditions today due to scant rainfall owing to the El Nino effect. Weather and Death in India, a study conducted by Tilburg University (Netherlands) over a period of 43 years starting from 1957 to 2000, has shown that annual mortality rate increases by a statistically significant 0.75% in those years when there is deficient rainfall! (1)

We have ourselves shown in the past as to how drought is the single biggest reason for anti-incumbency. Nearly 90% of all elections that follow a drought year throw away sitting governments.(2)Yet, the political class has not woken up to the drought problem after nearly seven decades of independence. It is a given that politicians may not care much about rural mortality rate, but if one believed that at least most politicians are consummate practitioners of the art of self-preservation, they fail here too.

It is in the interest of the politicians to tackle drought, for it directly impacts their electoral prospects. But, as we are witnessing even today in the state of Bihar, agrarian distress owing to monsoon failure is one of the biggest complaints that the voters have against the state government.(3) Had Nitish Kumar worked towards developing better mechanisms to tackle drought in his decade-long rule, no amount of Modi rallies or BJP strategies would have been able to defeat him!

In fact, Narendra Modi as chief minister of Gujarat emphatically showed how to win an election even in a severely debilitating drought year in the Saurashtra region in 2012 by better long-term agrarian planning. The same Narendra Modi-led government at the Centre today seems to be clueless as to how to handle a drought second year in the running.

This month, the central government has increased the annual number of the MGNREGA wage days from 100 to 150 as a solution to drought. After the Prime Minister having unequivocally criticized the NREGA on the floor of the house, all that his government has done is only repose more faith in a supposed symbol of Congress’s failure of 65+ years of governance!

Essentially these extra 50 days of NREGA mean more leakages, more corrupt money circulating in rural India and more of the same monkey business.(4)It is true that the primary responsibility of managing drought is that of the state government, but the Centre too has an important role at the level of policy making. The least one was expecting from the Modi government was a national rain/drought management policy to tackle this recurring problem, but even after a year and a half in office and despite having faced two straight years of drought no such thought process has been forthcoming. There are three aspects in which the central government’s role is vital in tackling drought;

Better resource management framework

Annual average rainfall in India is 1170 mm, which corresponds to annual precipitation(including snowfall) of about 4000 billion cubic meters (bcm). Out of this, about 1869 bcm is estimated as the average annual potential flow in rivers. On account of various constraints, only about 1122bcm of water is assessed as the annual utilizable water, having surface water resources component of 690 bcm and groundwater component of 432bcm.(5)

Improvement of irrigational facilities since independence has meant rapid expansion in the utilization of 432bcm of ground water – in 1950 only 6.5 million hectares of land tapped groundwater irrigation whereas today 70 million hectares of land do the same.(6)Most BJP ruled state governments have the policy of “more crop per drop” which is a laudable policy initiative, but at the central level one expects more comprehensive planning from the Modi government.

India is a vast country with a “large number of distinct hydrogeological settings. The occurrence and movement of ground water in various aquifer systems are highly complex due to diversified geological formations with considerable lithological and chronological variations, complex tectonic framework, climatological dissimilarities and various hydrochemical conditions.”

The only sustainable management of groundwater resources can be achieved by comprehensive mapping of aquifer systems. What the Modi government must have done is delineating aquifer recharge areas by computing the quantum of groundwater recharge through the integration of rainfall data, land use, soil types and surface water. It is only through such comprehensive data mapping that a national policy of “more crop per drop” can be truly achieved as a solution to seasonal drought.

Qualitative drought management

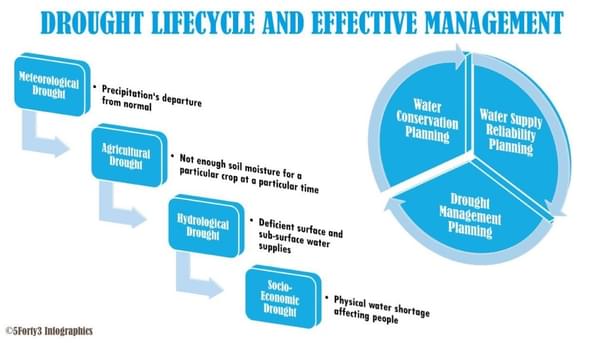

Every drought lifecycle has four distinct phases, but the problem in India is that we almost always reach the final phase each time because of lack of planned institutional response mechanism. One of the reasons for bad institutional response to drought in India is that early warning indicators in our country have a considerable degree of ambiguity. For instance, this year, like last year, there was quite a lot of disagreement on the degree of precipitation’s departure from normal throughout the months of June and July. This disagreement meant the government’s response was also not well calibrated at least till late July.

Until 2012, Earth System Scientific Organization and Indian Meteorological Department (ESSO-IMD) was monitoring drought using only two drought indices – percent deviation of rainfall from normal and Aridity Anomaly Index (AAI) – but since 2013 Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) on a monthly scale was also introduced.(7) This has meant better availability of data, but last two years have shown that the government’s institutional response has not yet been fully aligned to SPI. Modi government must not only develop better predictive data management regime but also develop a clear three-pronged drought management system where each component provides both temporary relief as well as long term solution to this debilitating problem.

Agrarian distress mitigation

Advance estimates released by agriculture ministry last week show that once again this year Kharif output is likely to drop to 124 million tonnes (mt), a negative growth of over 2 mt as compared to last year (126.3 mt) which in turn was lower than the previous year of 2013 (128.7 mt). In fact, over the last five odd years starting from 2010-11, Kharif production has been invariably falling while Rabi production share has been increasing. Even this year, the agriculture ministry has set an aggressive production target of 132.8 mt for the upcoming Rabi season.(8)

Classically, main agricultural cultivation season for India has been during the monsoon, spread between June and October (Kharif crops), but the last five years have shown that winter cultivation (Rabi crops) is proving to be the great saviour of the Indian farmer. Keeping this in mind, maybe it is time for the Modi government to pursue actively, a new long term strategy for shifting our agricultural focus from Kharif to Rabi crops and reducing the risks of over dependency on the South-West monsoon.

The second part of distress mitigation for an average farmer lies in agricultural insurance. Governments of past have only given doles to farmers in distress – loan waiver being a primary tool – which may have helped some political parties to win elections temporarily but have not made any material difference to a farmer’s life. All over the world, farmers mitigate drought risk by taking adequate insurance and Prime Minister Narendra Modi had aggressively pitched crop insurance as the next logical extension to PMJDY, but his government is failing in promoting insurance during this crucial drought year and has instead diverted resources to MGNREGA!

From 2006 to 2012, an IMF (International Monetary Fund) research team led by Shawn Cole and Xavier Giné among others had deployed a series of randomized field experiments in rural India to test the importance of price and non-price factors in the adoption of an innovative rainfall insurance product.(9) Their study comprehensively shows that despite being significantly price sensitive, rural agrarian insurance in India fails mainly because of non-price factors. In fact, they identify three clear problem areas as to why Indian farmers refuse to take-up insurance despite offering a pay-out ratio comparable to the US;

- Lack of trust

- Liquidity constrains

- Limited Salience

Even in our own surveys done in North Karnataka and Himachal Pradesh in 2011-12, we had found that more than 39% of distressed farmers were almost totally unaware of any government monetary assistance schemes to alleviate their problems. Thus, we realize that the Modi Government’s job doesn’t end with simply offering deep discounts for insuring crops and livestock but to drive its resources towards educating farmers and building trust in rural India towards adoption of insurance as an asset class.

If the central government concentrates on these three aspects and liberates Indian villages from regular drought, it would possibly be a rural achievement equivalent to Narasimha Rao’s “New Industrial Policy” of 1991. After 1991, Indian industrial growth finally took off and has never looked back since then. Can the BJP government set a similar trajectory for Indian agriculture starting from 2016? Prime Minister Modi owes this to every Indian in search of that elusive rain.

Sources on next page

Sources:

(4):URL: http://centreright.in/2012/07/14011/

(5):URL: http://www.cgwb.gov.in/

(6):URL: http://www.cgwb.gov.in/

(7):URL: http://www.imd.gov.in/

(8):URL: http://agricoop.nic.in/

Analyst of Indian electoral politics and associated economics with a right-of-centre perspective.