Politics

The Guilt Of Eminent Historians

Koenraad Elst

Feb 20, 2016, 06:56 PM | Updated 06:56 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Last month, a few marginal media reported that archaeologist KK Mohammed had a startling revelation on the responsibility for the Ayodhya controversy and all its concomitant bloodshed.

Young people may not know what the affair, around 1990, was all about. Briefly, Hindus had wanted to build a proper temple architecture on one of their sacred sites, the Ram janmabhoomi (Rama’s birthplace). So far, the most natural thing in the world.

However, a mosque had been built in forcible replacement of the temple that had anciently adorned the site: The Babri Masjid. Not that this should have been a problem, because the structure was already in use as a temple, and the site was of no importance to the Muslims, who never go on pilgrimage there.

So, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress Government was manoeuvring towards a compromise, allotting the site definitively to the Hindus, all the while appeasing the Muslim leadership. This was not too principled, just pragmatic, but it had the merit of being bloodless.

Unfortunately, this non-violent formula was thwarted. An unexpected factor came in between. It stimulated and hardened Muslim resistance and especially, it made politicians hesitant to move forward on Ayodhya. As a consequence, street rowdies took over, killing hundreds. The Hindu-Muslim violence culminated in multiple Muslim terror attacks in Mumbai on March 12, 1993, which set the pattern for later terrorist attacks from New York and Paris to Mumbai again.

On the other hand, it threw the issue into the BJP’s lap, making it the principal opposition party in 1991 and ultimately bringing it to power.

So, who thwarted the Ayodhya solution, thus creating a new type of terrorism as well as setting the BJP on a course towards power? Though the contentious site had no special value for the Muslims at first, it had suddenly become the Mecca of another influential community: The secularists. They made it the touchstone of secularism’s resistance against “aggressive Hindu fundamentalism”.

As a weapon against Hinduism, and as a way to whip up Muslim emotion, they alleged that the Hindu claimants of the site had been using false history. In fact, history was only peripheral to the Hindu claim on the site: It is a Hindu pilgrimage site today, and that ought to suffice to leave it to the Hindus. Yet, secularism’s favoured “eminent historians” insisted on interfering and said that there had never been a temple at the site.

Then already, the existence of the temple was known from written testimonies (Muslim and European) and from BB Lal’s partial excavations at the site in 1973-1974. Until the 1980s, the forcible replacement of the temple by the mosque had been a matter of consensus, as when a 19th century judge ruled that a temple had indeed been destroyed, but that it had become too late to remedy this condition. The British rulers favoured the status quo, but agreed that there had been a temple, as did the local Muslims. It is allowed for the historians to question a consensus, provided they have new evidence, but here they failed to produce any.

Yet, in a statement of 1989, Jawaharlal Nehru University’s ‘eminent historians’ turned an unchallenged consensus into a mere ‘Hindutva claim’.

It is symptomatic for the power equation in India and in Indology that this is a repeating pattern. Thus, in the Aryan Homeland debate, the identification of the Vedic Saraswati river with the Ghaggar in Haryana is likewise being ridiculed by secularist academics and their foreign dupes as a “Hindutva concoction”, though it had first been proposed in 1855 by a French archaeologist and has been accepted ever since by most scholars.

After the historians’ interference, the Indian mainstream politicians did not dare to go against the judgement of these authorities. The international media and India-watchers were also taken in and shared their hatred of these ugly Hindu history falsifiers. Only court-ordered excavations of 2003 have fully vindicated the old consensus: Temple remains were found underneath the mosque.

Moreover, the eminences asked to witness in court had to confess their incompetence one after another (as documented by Meenakshi Jain in Rama and Ayodhya, 2013): One had never been to the site, the next one had never studied any archaeology, a third had only fallen in line with some hearsay, etc.

Abroad, this news has hardly been reported, and experts who know it make sure that no conclusions are drawn from it. After the false and disproven narrative of the ‘eminent historians’ has reigned supreme for two decades, no one has yet bothered to demythologise their undeserved authority.

For close observers, the news of the eminent historians’ destructive role was not surprising. This writer had spoken on it in passing in his paper “The three Ayodhya debates” (St Petersburg 2011, available online), and in an interview with India First (January 8): “The secular intelligentsia… could reasonably have taken the position that a temple was indeed demolished to make way for a mosque but that we should let bygones be bygones. Instead, they went out of their way to deny facts of history. Rajiv Gandhi thought he could settle this dispute with some Congressite horse-trading: Give the Hindus their toy in Ayodhya and the Muslims some other goodies, that will keep everyone happy. But this solution became unfeasible when many academics construed this contention as a holy war for a frontline symbol of secularism”.

Facile dismissals are sure to be tried against this writer. They will be harder when the allegation comes from an on-site archaeologist, moreover a Muslim.

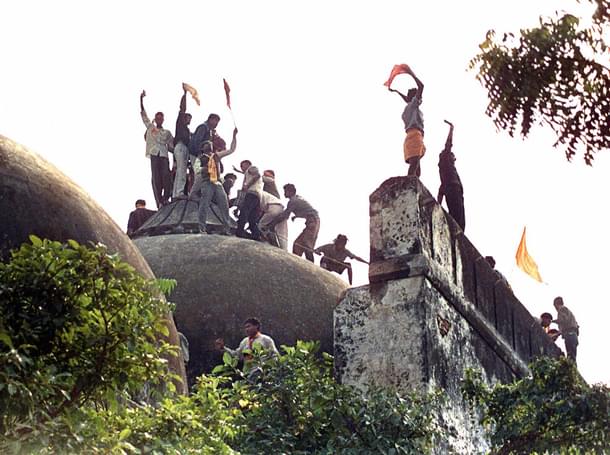

The media had allotted an enormous weight to the Ayodhya affair: “Secularism in danger”, “India on the brink” and similar headlines were daily fare. When the Babri Masjid was demolished by impatient Hindu youngsters on December 6, 1992, The Times of India titled its editorial, “A requiem for norms”, no less. Given all the drama and moralistic bombast with which they used to surround this controversy, one would have expected their eagerness to report Mr KK Mohammed’s eyewitness account. But no, they were extremely sparing in their coverage, reluctant to face an unpleasant fact: The guilt of their heroes, the ‘eminent historians’. These people outsourced the dirty work to Hindu and Muslim street-fighters and to Islamic terrorists, but in fact it is they who have blood on their hands.

This article was first published in The Pioneer on 26 January, 2016.

Koenraad Elst (°Leuven 1959) distinguished himself early on as eager to learn and to dissent. After a few hippie years he studied at the KU Leuven, obtaining MA degrees in Sinology, Indology and Philosophy. After a research stay at Benares Hindu University he did original fieldwork for a doctorate on Hindu nationalism, which he obtained magna cum laude in 1998. As an independent researcher he earned laurels and ostracism with his findings on hot items like Islam, multiculturalism and the secular state, the roots of Indo-European, the Ayodhya temple/mosque dispute and Mahatma Gandhi's legacy. He also published on the interface of religion and politics, correlative cosmologies, the dark side of Buddhism, the reinvention of Hinduism, technical points of Indian and Chinese philosophies, various language policy issues, Maoism, the renewed relevance of Confucius in conservatism, the increasing Asian stamp on integrating world civilization, direct democracy, the defence of threatened freedoms, and the Belgian question. Regarding religion, he combines human sympathy with substantive skepticism.