Politics

The Marginalised Flourished During Chola Reign: Why Pa Ranjith Must Read History

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jun 12, 2019, 10:26 AM | Updated 10:26 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Recently, when Pa Ranjith, a young upcoming Tamil filmmaker, who directed among other movies two of the recent Rajinikanth blockbusters — Kabali and Kaala — bad-mouthed the legendary Chola emperor Raja Raja I (947-1014 CE), it was not just bad history but also politics designed to be evil.

Ranjith claimed that the reign of Raja Raja Chola in particular and later Chola period in general was the dark age of Tamil history. This was because, according to him, that was when untouchability became well-established in Tamil Nadu and Cholas acting as stooges of Brahminism deprived the land rights which were enjoyed by those people which are today called scheduled communities. That such an attack comes when almost simultaneously a radical left ‘journalist’ spoke of ‘Dalits’ following Hinduism in abusive terms, is worthy of notice.

What Ranjith spoke is the received wisdom of the colonial version of Indian social history. The essence of this myth was that the Vedic Aryans enslaved the native Dravidians and through Vedic rituals imposed a rigid social hierarchy. Buddhism and Jainism challenged the Brahminical order and created an ethical, democratic people’s revival.

Then came the great period of Buddhist renaissance — but alas it was short-lived. Brahminism came back with the strategic alliance with despotic empire builders and elite culture. All that is called today dominantly as Indian culture is this Brahminical hierarchical elite culture.

However, with the coming of the ‘benevolent’ British colonialism, evangelism and enlightened Indology, the lost chapters of Buddhism and Jainism in Indian history were brought out. These historical ethical religions belonged to the marginalised sections of the society and naturally in terms of race, politics, religion and culture, the interests of the scheduled communities in India lay with the colonialists and not with the national movement which would only re-establish the Hindu Brahminical state.

When Marxists captured the post-colonial discourse, they simply perpetuated the colonial myth. While historian Romila Thapar and her acolytes present this in a suave manner and in ornate English in the academic ivory towers, it also percolates down to the society in the form of Brahminical conspiracy and victimhood atrocity literature of the distant past.

So everything a common Indian is proud of should not be considered with the same pride by scheduled communities. It does not matter that it was during the Gupta period that Buddhism in India produced two of its greatest achievements — Ajanta cave paintings and Nalanda University — both with state patronage from the empire, whose head professed Vedic religion.

Still the ‘Dalit’ narrative would claim that the Gupta period was actually a dark period because it was ‘Brahminical’. This effectively destroys a unified Hindu vision of history. A clever colonial seed of dividing the society is diabolically nurtured by academic Marxists and now propagated vigorously by an establishment media that thinks its privileges are being removed under the present dispensation.

But try hard as they did, they failed in North India. A left-wing academic informer for the Western universities lamented in his work how even the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) came around to project their elephant symbol as not just an elephant but as Ganesa identified with Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma. From “Tilak, tarazu aur talwar/inko maaro joote char” (give Brahmins, Vaishyas and Kshatriyas a beating with shoes) the BSP slogan transformed to become “Haath Nahin Ganesh hai, Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh hai” ('It is not an elephant, but Ganesh and is identical with Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva'). The frustration of ‘Breaking India’ forces at such developments could be easily guessed.

Now the same game is being repeated in Tamil Nadu. In fact, the state had been sort of a laboratory for testing the colonial racial theories in generating a counter-political narrative to national movement in order to facilitate both the evangelical agenda and subverting the national movement in favour of the Empire. So the British rule was seen as the liberator of the subdued non-Brahmin Tamils kept in ignorance by Brahmin agents.

The narrative sold well given the perceived or real dominance of Brahmins so explicitly noticed in the power structure of colonial administration. However, the narrative of an ancient Tamil grandeur has always run into a difficulty. The greatest achievement of Tamils, whether it is the sublime Bhakti literature or grand temples or the vast empires built by the Cholas or even the Sangam literature — all have roots in Hindu spirituality.

So the Dravidian movement fizzled out. But it did create harm in that it deepened the fissures and hardened certain fault lines. It was essentially against both the Brahmins and scheduled communities. To camouflage this, the movement often attacks Hindu spirituality and culture and raises the bogey of ‘Brahmin domination’. The unfortunate truth is that if those who sought real social emancipation, had they ever ventured into Hindu spirituality, they would have found the fountain of social justice there instead of making political movement out of pseudo-scientific race theories of colonial vintage.

Ranjith belongs to a new breed of Tamil ‘Dalits’, who think that the scheduled communities in Tamil Nadu do not share a common history with the rest of the Tamils. So if all the society praises Raja Raja Chola, they should abuse him as a tyrannical despot, who introduced in Tamil Nadu all the social evils. If one just goes through the actual historical data, one find’s an entirely different story. A Facebook attempt called ‘Vidhai’ or ‘seed’ (in which the present writer too played a very marginal role) to collate different primary sources on the actual state of the Paraiyar community in Tamil Nadu shows something drastically different.

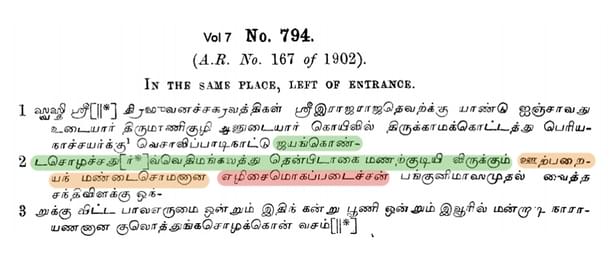

Ranjith says that it was during the time of Raja Raja that the lands of Paraiyars were taken away. But the inscription evidence right from the time of Raja Raja shows that one ‘Valluvan Manickam Manian’, who protected the people, was actually honoured and his descendants were given land. Yet another Chola inscription speaks about ‘Uur Paraian Mandaisoman Ezhisaimoha Padaichan’ who lived in the southern quarters of Jayamkonda Chola Chaturvedi Mangalam, who made donations to the temple.

Right through the Chola period, the Paraiyar community held many different positions in cultural and political life. They had been awarded and honoured. There had been chieftains, astronomers, navigators, physicians, musicians, village headsmen and weavers from this community. They made prominent donations to the temples — all these years before, and during the reign of and also after Raja Raja Chola.

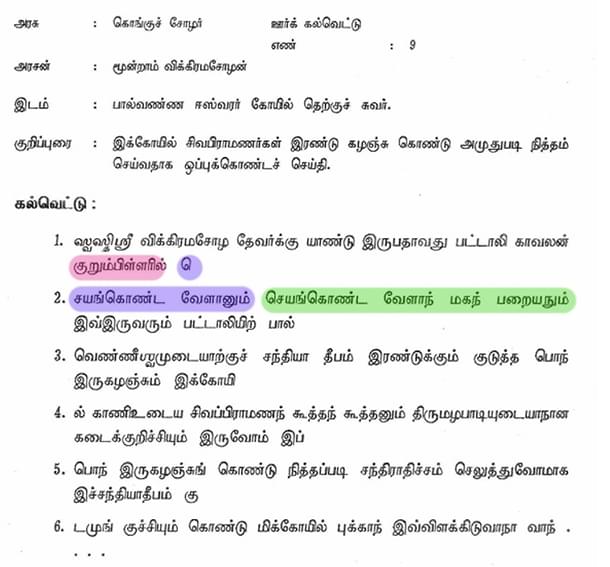

The word ‘Paraiah’ was not a despised name and the name was also given to the sons as a Chola period inscription belonging to Vikrama Chola time shows. The inscription says how after getting donations from one Jeyam-Konda Vellan and his son named Paraian for lighting the lamps every day, the ‘Shiva Brahmans’ of the temple promised them that they would carry out the duty. The inscription was made in the temple’s southern wall.

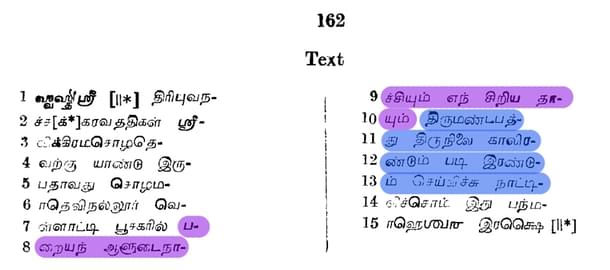

Yet another inscription belonging to the era of Vikrama Chola (12th century) speaks about “Paraiyan Aaludai Nacchi and the step mother” of the person who made the inscription who in turn had donated for construction work in the auspicious hall in the temple at Cholamadevinallur. The woman called ‘Paraiyan Aaludai Nacchi’ was referred to as ‘Velladi Pujaka’:

There are endless examples. Historian Professor Aloka Parasher-Sen succinctly gives a general picture of how Paraiyars were during the Chola period:

An inscription of Raja Raja III found at Kiranur at Kulatturtaluk, Pudukottai district says that two Paraiyas called Annooru Paraiyan possessed the titles of Per Araiyan and Araiyan and Natu Araiya. Some of them served as soldiers in the army. Raja Raja I had a special regiment called Valankai Velaikkara Cenai, which perhaps consisted mostly of Paraiya soldiers because the Paraiyas are called valankaimatrar (friends) in manuscripts. ...Among the signatories of some of the inscriptions found at Pudukottai are Ennankalakki Paraiyan, Uttamacola Paraiyan, Kanattu Paraiyan, and Aracar Mikamaparaiyan175 (pilot in a ship). They performed multifarious useful tasks such as field labourers, drum-beaters, weavers,performers of funeral rites, watchers in villages, etc. They seem to have possessed property of their own and paid taxes.Aloka Parasher-Sen, Subordinate and Marginal Groups in Early India, Oxford University Press, 2004, p.147

Had Ranjith ever cared to look into the real history of our people he would have found it all by himself. But he has an agenda. The agenda is to use his achievements in the film industry to widen the divide in the society and put the blame of the resulting violent social conflicts including honour killing on Hinduism. What’s more, one of the major deprivations of the Paraiyar rights happened during the British rule, which many establishment ‘Dalit crusaders’ project as a kind of enlightenment era.

All these historical data, of course, should not blind us to the presence of social exclusion and social discrimination that exists in Tamil Hindu society even today. But those who really fought against it did not build on the racial theories of the colonial era. Instead, they embraced Hindu spirituality and holistic conceptualisation of Indian history.

Swami Sahajananda (1890-1959) was a great ‘Advaitin’. When as a child he was asked who he was, he answered that he was ‘Para Brahman’. His guru Karapatra Shiva Prakas Swamigal initiated him into the spiritual discipline. The fire for social emancipation was lit in the mind of the non-dualist monk when he read Sri Bhakta Mahavijayam — a popular compilation of north Indian Bhakti saints.

The result has been that he created a movement that simultaneously worked on the minds of the dominant as well as marginalised sections of the society. Unfortunately, such spiritual mentors of the society are rare today — mainly because we have forgotten to celebrate such great visionaries. Instead, we have made pseudo-leaders, who with their borrowed colonial wisdom mislead the vital part of our society.

For all his confused thoughts and misleading rhetoric, there was one thing that Pa Ranjith got right. He visualised the entire Indian society as a body. The social discrimination and social exclusion are diseases which affect the entire body, he said. One cannot agree with him more. And the body needs to be healed with medicine and a good team of doctors — not charlatan solutions from quacks, who unfortunately offer hate-filled shallow, selective and faulty 'knowledge’ of history.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.