Politics

The Problem Isn’t Jinnah’s Portrait In AMU, But The Creeping Jinnah Mindset

R Jagannathan

May 02, 2018, 01:42 PM | Updated 01:42 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

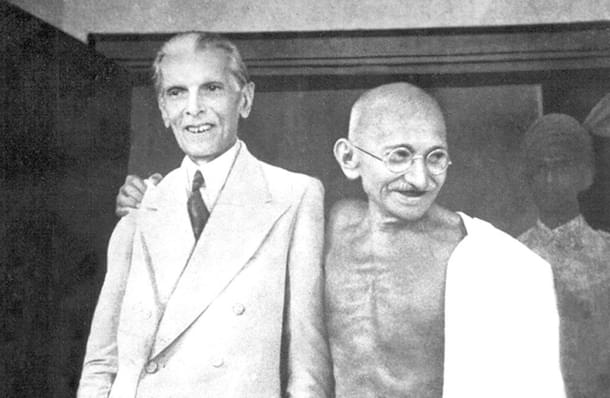

There was much indignant posturing on TV channels yesterday (1 May) over the discovery of a Jinnah portrait in the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), but this is essentially much ado about nothing. Jinnah’s association with AMU dates to 1938 when he was offered life membership by the Students’ Union – a few years before he formally raised the demand for Pakistan in India’s Muslim-majority provinces.

What should really concern us is not the portrait itself – which is a mere artefact of history – but the Jinnah mindset and the separatist mentality it engenders among Indian Muslims. This has given rise to a host of mini-Jinnahs in several parts of India, from leaders of the rump Indian Union Muslim League in Kerala, to the Owaisis of the All-India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (in Hyderabad and parts of Maharashtra), and the All-India United Democratic Front (AUDF) of Badruddin Ajmal in Assam. There are several smaller local Muslim parties in various states, but of greater consequence to the idea of Muslim separatism are the vocal leaders of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, who want India to be sharia-compliant (and we largely are), and the less visible leaders of organisations like the Tablighi Jamaat, which want to root out all syncretic practices among Indian Muslims.

Separatism and anti-syncretism is rooted in Islam’s history and Hadiths. The Prophet was once said to have advised his followers to differentiate themselves in as many ways as possible. “Do the opposite of what the pagans do. Keep the beards and cut the moustaches short.” Another piece of advice was to keep the hem of any garment above the ankle. You only have to take one look at the pictures of Owaisi and Ajmal to know that they follow this stricture religiously.

If differentiation runs deep in the Muslim psyche, political separatist thinking had its roots in two unrelated developments in the 18th century: one is the rise of Wahhabism in Nejd region of central Saudi Arabia, and the other is the gradual decline of Islamic rule in India with the rise of British colonialism. Many Muslim intellectuals of the 18th century traced the roots of the decline of Islamic power to their growing syncretism; it followed that to return to power, Muslims must remove all elements that make them similar to their neighbours from their practices.

The Wahhabi idea was first internalised in undivided India by a Bengali Muslim scholar called Haji Shariatullah, who travelled to Saudi Arabia and returned totally absorbed with the idea of purifying Indian Islam from alien influences. He aligned himself with the ideologies of Wahhab. Another key figure in this de-sycretisation of Islam was the founder of the Barelvi sect, Syed Ahmad Barelvi, who despite being a Sufi, wanted to make Sharia laws dominant among Indian Muslims. Support for Sharia is strong in Pakistan and Bangladesh, with 84 per cent and 82 per cent backing its introduction; though the Pew Research study which quoted this figure does not have data for Indian Muslims, it would be surprising if support for Sharia was not significant here too.

This is where Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and the Aligarh Muslim University come in. Though Khan was a moderniser and wanted Indian Muslims to be freed from the clutches of hidebound ulema, he was the father of Indian Muslim nationalism whose ideas ultimately led to the creation of Pakistan. He wanted Hindus and Muslims to unite to some extent, but not merge into a seamless nationalist force. He wanted them to be separate, but equal. According to Nadeem F Parcha, a columnist in Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper, “Pakistan nationalism is the direct outcome of Muslim nationalism, which emerged in India in the 19th century. Its intellectual pioneer was Sir Syed Ahmad Khan.”

Jinnah’s own separatism drew on this trend of Muslim mental separatism created by the likes of Shariatullah, Barelvi and Syed Ahmad Khan, who founded the Aligarh Muslim University (originally set up as the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875).

The Jinnah mindset can be defined as the constant and ever-present need for keeping Muslims in India separate from the rest of its people in as many respects as possible, whether it is in terms of personal laws, the creation of Muslim-only enclaves, the ethnic cleansing of non-Muslims from Muslim majority regions (Pakistan, Bangladesh, and more recently even inside India, in Kashmir Valley), or the refusal to accept yoga or Vande Mataram as part of their national heritage.

Tufail Ahmad points out that even the tallest “nationalist” Muslim who remained in India after Partition, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, essentially was a global Islamist. He too made calls for jihad when the Ottoman Caliphate was under attack.

His opposition to India’s Partition came from a Jinnah mindset; he wanted a united India so that a larger unified Muslim group could gradually make the whole of India Islamic at some point. On the other hand, Jinnah’s Muslim League demanded Pakistan to create a new Muslim country - a separate and sovereign space from which Muslims could gain strength and then seek to dominate India, as Venkat Dhulipala demonstrates in his book Creating a New Medina. This is the script being played out from Pakistan today, with jihadis being sent to Kashmir and other parts of India to Islamise it.

It is worth recalling that even the Ali brothers, Maulana Mohammad Ali and his brother Shaukat Ali, who willingly accepted Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership during the ill-fated Khilafat movement in the second decade of the 20th century, put Islam above their respect for the Mahatma. Mohammed Ali is reported to have said: “As a follower of Islam I am bound to regard the creed of even a fallen and degraded Mussalman [as] entitled to a higher place than that of any other non-Muslim irrespective of his high character, even though the person in question be Mahatma Gandhi himself.”

Put simply, the Jinnah mindset can be traced not to Jinnah himself, but the overall Muslim sense of separateness, and the belief that they cannot dominate India or any smaller place within it without separating themselves from the rest of the people in areas they live in.

It is also worth noting, as Dhulipala does in his book Creating a New Medina, that the idea of a separate Pakistan had its strongest support in the United Provinces, where Muslims were in a minority and had no hope of being a part of this separate country. In fact, the whole idea of a composite nationality (Muttahida Qaumiyat) that Congress-oriented ulema were touting was comprehensively defeated in the UP Muslim’s mind by two Deobandi ulema, Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanawi and Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani.

This separatist mindset was nurtured inadvertently by the Congress after Independence, which used Muslim fears to create a solid vote bank, by repeatedly raising the bogey or Hindu majoritarianism. Even though the BJP has moved some distance away from the old Congress minorityism – largely because Muslims anyway won’t vote for it in large enough numbers to make a difference – it persists with Congress policies of trying half-heartedly wooing Muslims by giving them favours through the minorities ministry.

Recently, the Prime Minister has been talking of Muslims improving their lot with his “Ek haath mein Koran, aur doosre mein computer” (Koran in one hand, and computer in the other), but one wonders why the head of a so-called Hindu party needs to remind Muslims about carrying the Koran in one hand. Is that any business of the “secular” Indian state?

The Jinnah mindset is worrisome because it has crept into many parts of India, including the ruling party’s leadership. Jinnah’s portrait isn’t the problem.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.