Politics

Three Reasons Why Indian Elections Are An Incumbent's Game Now

Abhishek Kumar

Sep 04, 2025, 01:28 PM | Updated Sep 05, 2025, 12:25 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The upcoming Bihar assembly election (AE), 2025 is being watched by pollsters for varied reasons, ranging from the impact of freebies to the nationalistic wave sweeping the nation in the era of Operation Sindoor and extreme geopolitical turmoil.

Anti-incumbency against anti-incumbency

For one section of observers, this election is about extrapolating their chart of India turning into a pro-incumbency democracy in the last decade. Nitish Kumar’s victory will provide an extra engine to the pro-incumbency train observed in recent times.

The reason is simple. If a chief minister who is described as senile can return to power after a 20-year-long tenure, which saw him becoming everything but the absolute destroyer of the state, then it is not just a mandate about him but also about a developing psyche of status quo government among Indians.

However, Kumar’s re-election, if it takes place, would not be as big a surprise as multiple states have churned out in recent elections. In Haryana AE, 2024, BJP surprised everyone by trouncing Congress in what was believed to be a one-sided pro-Congress contest by pollsters, on-ground reporters and studio columnists. The party punctured the narrative of anti-incumbency.

The story was similar in Maharashtra where the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won 81.5 per cent of total seats, nearly a 150 per cent jump over 35.41 per cent in General Elections (GE) 2024.

While the NDA bagged two most unexpected states, the Indian National Democratic Inclusive (INDI) Alliance did so in Jharkhand with the help of Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) leader Hemant Soren. Soren’s arrest and NDA’s success in Lok Sabha elections were seen as cause and effect, only to be proven wrong by AE results. Jharkhand was also the first loss of BJP’s stalwart strategist Shivraj Singh Chouhan.

These surprises are extremes due to their back stories. However, on pure statistics, they are one of the larger inflexion points in a changing pattern which is being seen in the Indian political spectrum.

Between the 10-year period of February 2015 and February 2025, 28 Indian states and Puducherry witnessed 60 elections. All of them went through at least two state election cycles as well as two general election cycles of 2019 and 2024.

Apparently, in 36 of those elections, the incumbents were able to secure their comebacks by one way or another. By and large, the voting majority of the state entrusted either the main face or the ruling party or coalition with five more years of the state’s fortune in 60 per cent of elections.

For instance, in the 2016 Tamil Nadu AE, AIADMK and coalition returned to power on the back of Jayalalithaa’s face, despite the possibilities of change of guards. On the other hand, in 2015, Bihar voted for Nitish Kumar, but with the changed coalition partner in the name of Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD). Even at a place like Madhya Pradesh, where Shivraj Singh Chouhan was voted out in 2018, his own brand value was a big factor in Jyotiraditya Scindia switching sides later.

Scores of such examples illustrate that the general public needs a certain form of reassurance in electoral results. A 60 per cent success rate is by no means a bad number. It means that an incumbent chief minister, party, or coalition wishing to secure re-election in India has a 60 per cent chance of doing it. If we include Lok Sabha numbers, which have witnessed two pro-incumbency waves in the last two cycles, the picture becomes clearer, even on the individual candidate level.

In the 2019 General Elections (GE), 337 MPs fought the elections, out of which nearly 67 per cent won. This rate was 66 per cent in 2024 GE as 216 out of 324 incumbents who contested the elections returned.

Between 1952 and 1977, India did not witness much anti-incumbency wave as Congress swept through most elections with little scope for regional ones. Emergency and Mandal-Kamandal polarisation opened a nationwide avenue which changed the nature of post-1977 elections into anti-incumbency. Between 1977 and 1998, over 60 elections were conceded.

Despite these 19 years of largely anti-incumbency waves, the 46-year period of 1952–1998 witnessed 90 per cent of incumbents returning to power, a fact which illustrated the 25-year dominance of 1952–1977. Interestingly, 90 per cent of verdicts between 1998 and 2019 were anti-incumbent, highlighted by volatility between 1999 and 2014.

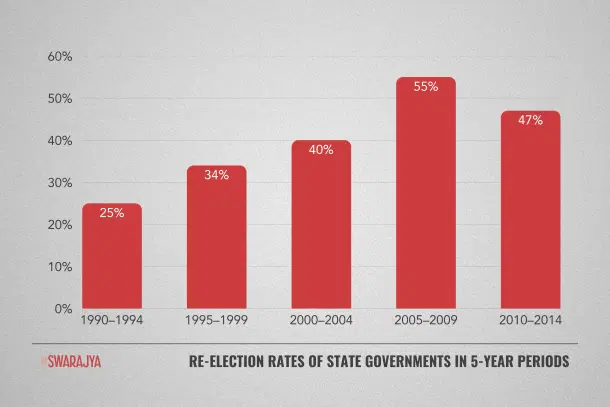

Analysis of the 40-year period between 1975 and 2015 showed that at any given five-year period, the probability of pro-incumbency varied between 25 to 55 per cent. The upper limit is still five per cent below the threshold of 60 per cent as seen between August 2015 and August 2025.

This significant departure from the norm is surprising because it is happening in the era when common sense says that the trend should have been exactly the opposite. The arrival of the Internet was supposed to take democratic fights to hinterlands and hence more voices of opposition should have emerged in consonance with more fragmentation of demands.

The latter has actually happened. Identity groups are no longer limited to statutory defined terms like Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) among others. Instead, the individual demands of constituent groups are propping up.

While the disruptions caused due to Jat and Patel communities seeking reservation in Haryana and Gujarat respectively have grabbed headlines, lesser disruptive demands like Maratha reservation, Vokkaliga quota and Nishad reservation are also there. Then there are substantiated allegations of a few communities among OBCs, SCs and STs gobbling up the majority of the reservation pie.

While Meenas, Yadavs and Kurmi-Kushwahas share these accusations in North India, Vanniyars, and Kurubas get the heat in South India.

These explain why the attempts to politicise and organise mass agitations against the Supreme Court’s judgement on sub-categorisation did not gain traction. The binding glue was simply not there.

At this point, most identities in India are targeted voting blocs, Muslims being on the radar of Congress, regional parties and secular ones. The percentage of OBCs, SCs and STs ensures that no party can afford to ignore them. The same holds true for women, who are often known to transcend caste and even religious boundaries in favour of welfarism, cash incentives, dignity and employment opportunities.

Virtually every party has targeted everyone except general category men, for whom EWS reservation remains a single most state-sanctioned support.

With so many social divisions coming to the fore, it is easy for the opposition to snatch a share and disadvantage the incumbent, but it is not really happening at the scale seen between 1977 and 2014.

What explains it? Why do people divided erstwhile come together to press on the incumbent symbol? Let us explore it.

Three Pillars Of Voter Loyalty

The first most crucial factor behind this trend is the delivery of democratic rights, which the Indian psyche is not really habituated to. In the middle of the anti-incumbency wave, Rajiv Gandhi had infamously said that only Rs 15 out of Rs 100 sent out by the government actually reached beneficiaries.

The majority in India’s rural areas, known for voting in higher proportion than urban, lacked access to quality food, shelters, roads, stable income and basic opportunities for livelihood. This changed with the onset of Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and the Jan Dhan Aadhar Mobile (JAM) trinity. Both have been influential in ensuring that benefits of housing schemes, cash transfers, subsidies, business loans and even salary payments under MGNREGA reach directly to the accounts of beneficiaries.

State-specific targeted benefits, ranging from cooking gas cylinders in Uttar Pradesh to Rythu Bandhu by KCR, have been some key successes in the era when DBT became a norm. Even before DBT, the governments which were effective in grassroots delivery were more successful.

For instance, Raman Singh, former chief minister of Chhattisgarh, was profoundly named as Chawal Waale Baba for his foodstock delivery initiatives. In the adjacent Madhya Pradesh, Shivraj Singh Chouhan received the Mama moniker for similar reasons. Both enjoyed a healthy track record of having pro-incumbency in their favour. Jayalalithaa and Mamata Banerjee being called Amma and Didi for their respective initiatives are other prime examples.

A recent estimate published on the Press Information Bureau revealed that DBT has resulted in cumulative savings of Rs 3.48 lakh crore by plugging leakages.

Politicians have also learnt to time their initiatives so that their impact could be seen on votes being cast. A NABARD study found that between 1987 and 2020, 21 incumbents announced farm loan waivers before state AEs, out of which 17 emerged as victorious.

Another study by SBI on Madhya Pradesh said, “We estimate that a 1% point increase in the marginalised women targeted (receiving Ladli Behna), has increased the district-wise electoral success rate of the incumbent party by 0.36%. Juxtaposing such into a district-wise electoral success rate, it can be said that every 1 in 8 constituencies, on average, had a favourable outcome (pro-incumbency) due to Ladli Behna, 30–35 seats in at least 8 districts.”

These must have crossed the minds of the respective teams of Eknath Shinde and Hemant Soren when they announced Mukhyamantri Majhi Laadki Bahin Yojana and Maiyya Samman Yojana in the run-up to state elections.

Reportedly, in Jharkhand, the cash was transferred to beneficiaries’ accounts in the lead-up to election dates. Nitish Kumar is now trying to do the same for women and old citizens in Bihar by announcing Rs 10,000 for women and increased pensions for senior citizens in the lead-up to elections.

The second major factor is that of road connectivity to villages. The Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) has shown the way. A UPA-era study by Camille Boudt Reddy and Andre Butler found that roads built under PMGSY during that era helped the UPA usher in with 7.3 per cent more votes.

“This suggests long-term political benefits to investment in public infrastructure. What is more, the political gains are not limited to the direct beneficiaries of the PMGSY programme. We find evidence that non-beneficiary villages within a 2 km radius of a newly constructed rural road also increase their vote share to the UPA by a similar amount,” the study added.

In the northeast, the Bogibeel Bridge connecting Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, the Dhola-Sadiya Bridge linking Assam to the easternmost corners, the Agartala–Akhaura rail link boosting trade with Bangladesh, and new airports in Sikkim, Itanagar and Pakyong have proved to be transformative.

Riding on these headline developments and thousands of kilometres of new connectivity projects, BJP has established itself as the dominant force in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Tripura. Apparently, the party termed as nationalistic benefitted from enhancing the connectivity of an erstwhile obscure location to mainland India.

Another study done by Amrita Dhillon of King’s College London, Ahana Basistha of TU Munich and Arka Roy Chaudhuri of Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence found that between 2000 and 2013, road sanctioning surged by 40 per cent in the fourth year of a politician’s five-year term.

This explains why there is a rush by politicians to announce every single project of public importance from their public platforms. This writer has grassroots examples of ministers inaugurating a project and then local politicians rushing to the site after a few weeks and redoing it.

A scan of politicians’ social media feeds before and after 2014 marks a clear shift. Earlier, their posts largely revolved around state and national political developments or big-ticket projects impacting large populations. Today, many scramble to showcase, even claim credit for, the construction of a single kilometre of road.

One may be tempted to point out the failure of BJP’s 2004 loss on this parameter. However, that loss had more to do with the overconfidence of Pramod Mahajan advising then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to call early elections in the backdrop of stupendous victories in the 2003 assembly elections of BJP in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

The third common factor in these pro-incumbency results is how political chessboards are being set up. The targeting of voters is incredibly minute and the fight is now being taken at both rallies and algorithms. A closer look at elections held between 2021 and February 2025 will tell you that offline versions of echo chambers have made a transition to the online world.

Social media, which was supposed to provide space for rigorous exchange of ideas and conflicting political ideologies, now just serves as a conformist space for most of us. Two people debating on a topic are fed with ideologically aligned information and just keep hammering the point without considering the other side’s point of view.

In a fragmented identity landscape, such exchanges do not change ideas but rigidify existing ones. For political parties, all of it means that they just need to focus on maintaining core vote banks through social media outreach. Regarding earning new voters, they would actually need to put more effort into groundwork, a shortcut way of doing it would be getting the biggest leader of such communities on their side.

BJP has been more successful on this front by doing so with Nishads in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. In Tamil Nadu, major parties allied with the PMK led by Vanniyar leaders to swiftly capture this key vote bank. In Andhra Pradesh, Congress consolidated support by bringing powerful Kapu and Reddy leaders on their side. In Karnataka, parties relied on Lingayat religious leaders and Mathadhipatis for quick endorsement, anchoring strong community support in elections.

Broadly speaking, efficient delivery of benefits, infrastructure projects and minute election engineering have paved the way for this latest pro-incumbency wave in a country where 800 million still seek government-aided food stocks.

The Wave Factor

Interestingly, there have been some significant deviations from this pattern as well. The latest of these was the ousting of Arvind Kejriwal and his Aam Aadmi Party from Delhi in February 2025. Not only did Kejriwal lose himself, but AAP’s core appeal of urban civic amenities and welfare state promises was also transferred to BJP.

A comparison of waterlogging under Minto Bridge in Delhi during AAP and BJP serves as an insight into it, even though the BJP government is facing heat for floods. Delhi’s example is also essential for Punjab since AAP was able to secure victory in 2022 riding on these promises only. Now, it stands at the risk of losing national party status too.

Other major upsets include Karnataka giving 135 seats to Congress in 2023, Yuvajana Shramika Rythu Congress Party losing to NDA in the 2024 Andhra Pradesh AE, Congress losing to AAP in the 2022 Punjab AE, BJP losing Himachal Pradesh in the 2022 AE and Naveen Patnaik losing Odisha in the 2024 AE.

While all being remarkable exceptions from the norm, there is one common factor in these results. That factor is that of big statewide waves sweeping the state.

The wave effect is clear when comparing seats lost by incumbents with seats gained by winners. In Andhra Pradesh, YSRCP collapsed from 151 to just 11, while the TDP-led alliance surged to 164 from 23. This was all thanks to built-up anger against it, capitalised on by Naidu’s arrest and the insult to Pawan Kalyan.

In Punjab, Congress crashed by 59 seats, allowing AAP to climb to 92. The turnaround was made possible by AAP’s continuous support to agitating farmers, which helped them sweep rural voters in the state. For urban voters, their Delhi model worked. In Delhi, AAP saw their seat share crashing by 40 seats, almost perfectly mirrored by BJP gaining 40.

The primary factor here was AAP losing its appeal of civic infrastructure and clean governance. For AAP, it was déjà vu in the sense that they had defeated Congress on the same planks.

Karnataka showed BJP losing 38 seats as Congress gained 55, and in Himachal, BJP’s 19-seat drop enabled Congress’s modest 12-seat gain. While Karnataka was the first major election in recent years where Congress unapologetically played its minority vote bank politics on the front foot, in Himachal it was largely about infractions as BJP faced its rebels on 21 out of 68 seats.

Another major surprise was the loss of Naveen Patnaik in the 2024 AE. Biju Janata Dal’s seat share plummeted from 113 to 51 while BJP’s shot up from 23 to 78. The major constituent of the wave in Odisha included BJP capitalising on the grip of Tamil Nadu-born officer V. K. Pandian and Patnaik’s own deteriorating health.

Most of the anti-incumbencies have stood up to the definition of the word ‘anti’ here. When people were convinced that the presence of local government or representatives was antithetical to their needs, they threw them out. A slight deviation from the pattern was BJP losing Madhya Pradesh to Congress. Here again, Mama was not particularly unpopular, which was crucial in BJP coming back to power with new leaders joining its ranks.

The Face Factor

This is one factor why BJP does not have a problem with Nitish Kumar being the face of NDA efforts in Bihar despite him being unpopular. His unpopularity has not reached the scale of Lalu Yadav in 2005, Manmohan Singh in 2014 or Jagan Mohan Reddy in 2024. People of Bihar expect better from him, but it is not as if they do not want Kumar back in power.

Kumar is one of those faces which define pro-incumbency trends in recent times. His balancing of welfarism along with the image of a strong-willed politician has meant that his core voters, women and non-Yadav OBCs, stuck by him without much care for his coalition partner. That explains why despite the failure of the alcohol ban, Kumar is not able to reverse it.

In the 2016 Tamil Nadu AE, Jayalalithaa’s Amma charisma and welfare schemes delivered a rare consecutive term in a state known for anti-incumbency. Describing her personality cult in the book The Pro-Incumbency Century: How Leaders Are Fashioning Repeat Mandates in India, Sutanu Guru and Yashwant Deshmukh write: “Just imagine. A deeply patriarchal state steeped in Dravidian angst against upper-caste Hindus revering and virtually worshipping a corrupt convict, temperamental, vindictive and Brahmin woman. This is what a personality cult is all about and we are seeing more and more of it across India.”

A similar story is there in West Bengal as well. Both 2016 and 2021 saw Mamata Banerjee’s Didi persona overcome the blitzkrieg by opposition parties. In the same year, Kerala also broke its four-decade alternation cycle due to Pinarayi Vijayan’s Captain stature in disaster and pandemic management.

In Assam (2021), Himanta Biswa Sarma’s personal authority consolidated BJP’s hold, and in Odisha (2019), Naveen Patnaik’s incorruptible image and welfare outreach insulated BJD from national party inroads. Uttar Pradesh (2022) is mainly credited to Yogi Adityanath’s cult-like Hindutva and disciplinarian appeal, while Delhi’s 2015 and 2020 mandates leaned almost entirely on Arvind Kejriwal’s positioning as an anti-establishment reformist and welfare-focused CM.

The Implications

The incumbents’ persistence has long-term implications for policies and politics. Now it is inevitable for the state not just to keep the status quo but also to keep delivering on the basic human rights of citizens, with the efficiency seen in the last decade. The delivery is a new normal and any new policy will have to take it into account.

This delivery-centric politics has weakened the ideological appeals of opposition parties, especially regional ones. In state after state, challengers find themselves promising larger versions of the same subsidies rather than putting out alternative development models.

In Madhya Pradesh, for instance, Congress countered the BJP’s Ladli Behna scheme by pledging its own scheme named Nari Samman Yojana. In Karnataka, its 2023 campaign was built on a ‘five guarantees’ package. BJP tried the same with Jharkhand women as well.

In Bihar, INDI Alliance and Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party (JSP) have also come with their own cash incentive announcements. Clearly, freebies or welfarism (as termed by politicians) are here to stay for the long term and the politics around them are going to be only uglier and uglier, as is the case with affirmative actions such as reservations.

Regarding fiscal health? Except for policy advocates, no one else is worried about it.

Secondly, pro-incumbency trends also put reliance on central figures like Narendra Modi at the national level, Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal, Nitish Kumar in Bihar, Hemant Soren in Jharkhand, Shivraj Singh Chouhan in Madhya Pradesh, Raman Singh in Chhattisgarh, Yogi Adityanath in Uttar Pradesh, Jayalalithaa in Tamil Nadu and Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra Pradesh.

Such rigidity reduces the incentive for local leaders to work on public infrastructure beyond headline schemes. It is now a widely accepted narrative that most voters are anti-incumbent against their local MLAs and MPs but pro-incumbent for heads of the respective states.

As one local journalist from Uttar Pradesh candidly put it: “Remove Modi and Yogi; I will leave my profession even if half of them could secure victory on their own, even ministers.”

That explains why there is little care about crumbling civic infrastructures among local MPs and MLAs. Most of them expect to make electoral comebacks on the main face projected by the party.

At the leadership level, it often means that parties fail to cultivate a second generation of leaders with statewide appeal. In most of the aforementioned examples, parties have struggled to generate a second crop of leaders who could confidently take on the mantle like Yogi, Nitish or Narendra Modi himself did in their times.

Most of the second-generation replacements struggle for recognition, as seen in the case of recent chief ministers and party heads chosen by various parties.

Voter apathy, especially in urban areas, in the short term is another consequence of the pro-incumbency phenomenon. While rural voters have much to gain from voting, a major section of urban India does not feel that their voting would have any impact on their fortunes.

When voters see outcomes as predictable, either because incumbents appear unbeatable or the opposition lacks credible alternatives, abstentions rise.

Voters are rewarding delivery and familiarity, not upheaval. The very forces that once fractured politics, identity divisions, coalition churn and mass agitations, are now contained within a system where incumbents start with an advantage.

Most elections are largely an incumbent’s election to lose.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.