Politics

Was Lal Bahadur Shastri Murdered?

Anuj Dhar

Jan 11, 2018, 12:03 PM | Updated 12:03 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

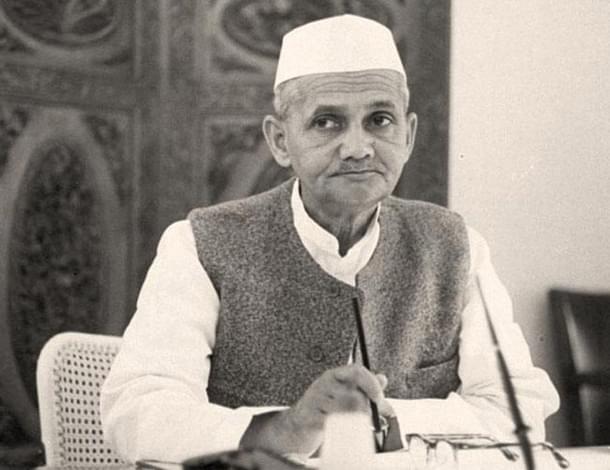

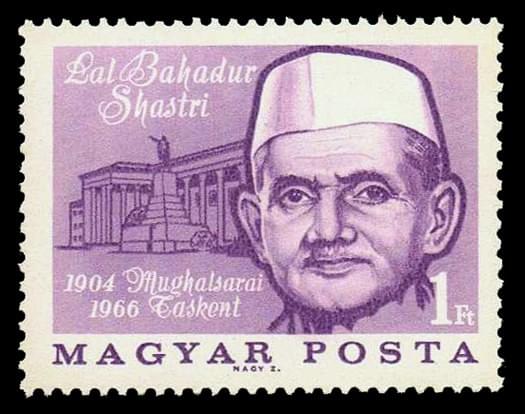

Today is the day to recall the great tragedy that befell India 49 years ago. For the first time in modern world history, a head of government died in a foreign country. Lal Bahadur Shastri’s sudden demise barely two years after his taking over as the Prime Minister shocked the nation so much so that deep down in our collective memory a pain lingers till date.

When Shastri’s body was brought home, his mother, who would die nine months later, spotted bluish patches on her son. “Mere bitwa ko jahar de diya!” (My son has been poisoned!) she cried out.

But then, doubts about Shastri’s death had cropped up even in Tashkent. On 11 January, at about 4 am, Ahmed Sattarov, the Russian butler attached to Shastri, was rudely woken up. The butler recalled his nightmare last year in an interview with Russia and India Report:

Early in the morning, I was woken by an officer of the Ninth Directorate of the KGB (who guarded members of the Politburo and the government), from whom I learned about the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri. The officer said that they suspected the Indian Prime Minister had been poisoned. They handcuffed me and three other head waiters, of which I was senior, and loaded us into a Chaika automobile. We four had served the most senior officials, and so we immediately came under suspicion.

They brought us to a small town called Bulmen, which is about 30 km from the city, locked us in the basement of a three-story mansion, and stationed a guard. After a while, they brought the Indian chef who had cooked the Indian dishes for the banquet. We thought that it must have been that man who poisoned Shastri. We were so nervous that the hair on the temple of one of my colleagues turned gray before our eyes, and ever since I stutter.

Sattarov was eventually given a clean chit by the KGB, but the Indian chef referred to by him has not been absolved by Shastri’s kin till date.

Shastri’s son Sunil and his grandson Siddharth Nath Singh, a senior BJP leader, continue to hold deep suspicions that the former Prime Minister’s death was not natural. Sunil’s elder brother and senior Congress leader Anil also wants things to be clarified.

On that fateful day in Tashkent, Shastri looked agile and healthy, though he had suffered a minor heart attack in 1964. Following the signing of the agreement with General Ayub Khan at 4 pm and a public reception at 8 pm, he reached the villa where he was staying. There, he had a light meal prepared by Jan Mohammad, personal cook of T.N. Kaul, the Indian Ambassador to Moscow. At about 11.30 pm, Shastri had a glass of milk. When his personal staff took leave of him, he was fine.

At 1:25 am, the Prime Minister was awakened by severe coughing. He himself walked out to tell his personal staff to summon his personal doctor R.N. Chugh from another room in the villa. The doctor arrived to find Shastri in his death throes as a result of symptoms of a heart attack. Dr Chugh made frantic efforts, but in vain. Then he started crying, saying that Shastri “did not give him enough time”.

In February 1966, the Shastri death issue was first raised in Parliament. A surgical cut and bluish patches on the Prime Minister’s body had been fuelling the poisoning rumours. However, the government response did not satisfy the lawmakers.

It was in 1970 that the issue could be discussed at length. Inspired by the success of the Opposition MPs in compelling the Government to probe Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s reported death afresh, Shastri’s well wishers and family members demanded an enquiry into the former Prime Minister’s death. In April 1970, Rajya Sabha MP and Shastri’s childhood friend T.N. Singh claimed that the family’s demand for an autopsy to rule out poisoning charges was rejected by acting Prime Minister Gulzari Lal Nanda.

The demand for a proper inquiry into the former Prime Minister’s death was repeated by Singh and others, but was turned down by the then government. Russian doctors explained that the blue patches on the body were due to the injecting of preservatives into the body.

The tragedy lived on in public memory. A former director of the erstwhile Information Service of India of the Ministry of External Affairs informed this writer that “a glass of milk was brought for Shastri by personal servant of Indian Ambassador T.N. Kaul” (Jan Mohammad) who “was never questioned or interrogated by anyone in the Soviet Union or in India despite his being the prime suspect”. Shastri’s family holds similar views.

In 2009, I made an attempt to get clarity on the matter, taking the Right to Information route.

The Prime Minister’s Office told me that it possessed only one classified document relating to the former Prime Minister’s death and there was no record of any destruction or loss of any document related to the tragedy.

The Ministry of External Affairs informed me that the concerned division had no information on the subject matter. It was quite strange because the sudden death of the Prime Minister must have thrown the Indian Embassy in Moscow in a tizzy. Ambassador Kaul must have scrambled to inform Delhi of the tragedy. A flurry of telephone calls and telegrams over the tragic development would have ensued for sure. The ministry would have gone on an overdrive to find out the circumstances leading to the Prime Minister’s death. The ambassador must have been asked to send blow-by-blow reports, and he must have done that.

The Soviets would have felt obliged to tell Indians about their handling of the matter too. And as the charges of foul play emerged, the government, through the Ministry of External of Affairs (and also the Intelligence Bureau, which was then responsible for foreign intelligence), must have tried to get to the bottom of the story. How could the concerned division in the ministry have no records?

The MEA further stated that the only main record available with the Indian Embassy in Moscow was the report of the joint medical investigation conducted by Dr Chugh and the Soviet doctors. The ministry confirmed that no post mortem was carried out in Moscow. I also got to know from the Delhi Police through another RTI reply that no post mortem was conducted in India either. Only an autopsy could have completely ruled out the poisoning charges.

On 21 July the same year, I filed another application seeking copies of the entire correspondence between the MEA and the embassy, and between the embassy and the Soviet foreign ministry over the issue. I requested the ministry to clearly say so in case no such records were extant. In its belated response, the MEA refused to release the information, for doing so would “harm national interest”. I was even denied a copy of Dr Chugh’s report even though it was not a classified record.

It was only after the intervention of Chief Information Commissioner Sadananad Mishra that the MEA in August 2011 supplied me copies of Dr Chugh’s medical report and a copy of the statement made by the External Affairs Minister in the Rajya Sabha. The medical report attributed the cause of death to “an acute attack of infarct miocarda (myocardial infarction)”.

The issue about the sole secret record held by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) was also settled by commissioner Mishra in June 2011. After hearing the PMO and my views, he summoned the classified record to decide whether or not it could be made public. The record was shown to him and he ruled that the PMO was right in keeping it classified, for its disclosure would indeed harm India’s relations with a friendly nation.

Later I learnt that this record cited an intelligence report blaming the United States, most likely the CIA, for spreading a “canard” that Shastri’s death was not natural. To me, this version is a mere conspiracy theory because available information indicates that the Americans sensed no foul play and saw no Russian hand.

For Shastri’s son Sunil and grandson Siddharth Nath Singh, the needle of suspicion points towards Indians. They have grave suspicions about the fate of Dr Chugh and another attendant of Shastri. Dr Chugh, his wife and two sons were run over by a truck in 1977. Only his daughter survived—crippled.

There are those who link Shastri’s death to the mystery surrounding Subhas Bose’s disappearance. Jagdish Kodesia, a former Delhi Congress chief and a confidant of Shastri, appeared before the Khosla Commission (formed to probe Netaji’s ‘death’) in March 1971 as a witness. Several times during his on-oath deposition, Kodesia stated that “Shastriji was one person” who did not believe in Netaji’s death in a plane crash. “When he became Home Minister…he wanted to know the truth whether Subhas Bose was alive or not.” Kodesia felt that “after he became the Prime Minister…[Shastri] was emphatically working that there should be a fresh probe into Netaji’s disappearance”.

Kodesia’s words above, now part of a record preserved in the National Archives, are spine-chilling. This nation owes it to the memory of Lal Bahadur Shastri that all official records about his death, especially those held by our intelligence agencies, must be released in full. And the disclosure must be followed by a request at the highest level to the Russian Federation and Uzbekistan for sharing all that they know about the issue.

The Shastri family must take up the matter with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. There has to be a full accounting of facts, a final reckoning in national interest.

For more than a decade, Anuj Dhar has devoted himself to resolving the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Subhash Chandra Bose. His 2012 bestselling book India's Biggest Cover-up (Netaji Rahasya Gatha in Hindi) triggered the demand for declassification of the Bose files.