Politics

What Ayodhya Dispute Needs Is Legislative Intervention, Not Judicial Arbitration

Vikas Saraswat

Nov 10, 2018, 11:36 AM | Updated 11:35 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Ever since sarsanghchalak of Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh(RSS) Mohan Bhagwat echoed the widespread Hindu demand for paving a quick way towards temple in Ayodhya, several other luminaries and an important body of seers - Akhil Bharatiya Sant Samiti have asked the central government to enact a legislation or bring in an ordinance to build the Ram temple at Ayodhya.

With the matter pending in courts for seven decades, the patience of the Hindu society is running thin. Disregarding the Hindu sensitivities, the Supreme Court has declared that resolution of the case is not a pressing concern for it. The court has said that a bench would be constituted only in January next year and it will be up to the bench to commence hearings at a time of its choice. The hopes of crores of Hindus who have been waiting patiently for resolution of the case were given a major fillip when final hearings began on 8 February this year(2018).

The fact that no new evidence is expected to surface and that there is enough material evidence to adjudicate the case, including an unambiguous report by the Archaeological Survey of India(ASI) on the findings below the demolished structure, should have well enabled a judgment in eight long years the case has been in Supreme Court. But the apex court in its immense wisdom has decided to defer the hearings once again. The delay, in a way, has corroborated the demand made by senior lawyer and Congress leader Kapil Sibal representing the Sunni Waqf board. Sibal had wanted the hearings to be stopped until 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

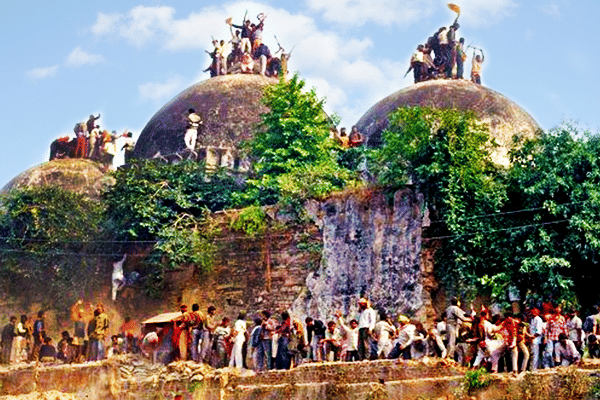

The overall disappointment among Hindus is similar to that in 1992 when court indolence left the structure demolished. In October 1991, the Uttar Pradesh(UP) government had acquired two plots of land around the structure. The acquisitions were challenged in both the High Court and the Supreme Court. In November 1991, the Supreme Court transferred all the writs filed with them also to the High Court with an assurance that the latter will take them up for final hearings in December 1991. But the hearings were still continuing in July 1992 when Kar Seva, proposed long back by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad(VHP), was about to come up.

The Supreme Court once again assured that it will take up all the cases for disposal provided the UP Government could prevail upon the VHP to withdraw the Kar Seva. VHP obliged by deferring Kar Seva to the fateful day - 6 December 1992. The Supreme Court, however, went back on its promise saying the hearings in the High Court were already in an advanced stage. The High Court finished the hearings on 4 November but delayed the judgment to 11 December 1992. Fervent pleas to both the courts by the state government for judgment before 6 December were turned down saying, “Courts would not function under any pressure”. One of the High Court judges went on leave. The court delivered its judgment on 11 December striking down the acquisition. But Babri’s fate had been sealed. The structure had already been razed to the ground.

Reflecting on the judicial delay, Girilal Jain, the legendary editor of Times of India wrote: “Courts could not be particularly useful, however elevated their view of themselves and however great the trust in them of the proponents of Rule of Law”. Writing on the delay and “sense of exasperation that accompanied the failure of the subordinate courts to resolve the outstanding litigation”, Swapan Dasgupta, then a senior editor at The Indian Express observed “After all, in its order of November 15, 1991, the Apex Court had assured the litigants that the High Court “is taking the case for final disposal sometime in December of this year”. A failure to meet the deadline by a few weeks is understandable but when “December of this year” stretches to “December next year”, some explanation is called for”.

From incremental writs to requests for a larger bench, all kinds of tactics have been used to delay hearings in Ramjanmabhoomi case. Until 2018, eight years since the case had come to the Supreme Court, only supplementary matters were being heard. One such supplementary matter was the revival of ‘Ismail Farooqui versus Union of India’ case pertaining to whether a mosque was integral to Islam or not. A larger five-judge bench had already settled the question in 1994.

Given the old record and the lack of enthusiasm of the Supreme Court, an early resolution of Ayodhya dispute in the Court is highly unlikely. The dispute will have to be addressed politically. But the delay is not the only reason that legislation is needed. The courts have been hearing the matter as a title dispute whereas it is much more than that. The final verdict which comes out of such a narrow understanding of the dispute could create more complications than it resolves. For instance, the High Court verdict which ruled that disputed land be divided into three parts with two third in favour of Hindus and one third to Muslims would have left the situation on the ground even more vexatious.

The verdict was universally seen as an exercise in arbitration and not really justice. In an interview to Rediff News, Madhav Godbole who was the home secretary at the time of Babri demolition summarised it for all when he said “this verdict is more in the nature of arbitration than deciding on the title of the land. The judges have tried to find an amicable settlement of the issue. Now that is not the charter of the court.” Having confined itself to a narrow scope, in all likelihood a Supreme Court judgment would be a repeat of such arbitration with a little more give and take one way or the other.

The only time when the Supreme Court was approached with a proper concern was in 1993. The government sought a Presidential reference under section 143 of the constitution seeking court’s opinion on whether or not a temple existed prior to Babri Masjid at the disputed site. Both sides to the dispute had also agreed that this indeed was the “core question”. What happened to the reference is recounted here in Arun Shourie’s words. “Barring holidays and summer vacation, five judges of the Supreme Court heard the case three days every week from February to September 1994. And, alas! In the end they decided not to answer the Reference at all.”

The “core question” in Ayodhya dispute has, in fact, an even wider frame. That frame is about civilisational wounds which India has suffered. Not only is India littered with provocative monuments of national shame, but these are also celebrated under the ruse of secularism. Renowned historian Arnold Toynbee, while delivering the Azad memorial lecture in 1960 defended the demolition of an Eastern Orthodox Church by Polish Roman Catholics in a city square at Warsaw in late 1920s. He said “I do not greatly blame the Polish Government for having pulled down that Russian Church. The purpose for which the Russians had built it had not been religious but political, and the purpose had also been intentionally offensive”, Relating the same with India, he spoke about temple destruction by Muslim rulers. Singling out Aurangzeb’s mosques in Kashi and Mathura he added, “Aurangzeb’s purpose in building those three mosques was the same intentionally offensive political purpose that moved the Russians to build their Orthodox Cathedral in the city centre of Warsaw. Those three mosques were intended to signify that an Islamic Government was reining supreme, even over Hindustan’s holiest of holy places.”

Such monuments also might have been tolerable, if Islamic imperialism in India had been a thing of past. Partition of India, continuing Jihad in Kashmir, devious settlement of Rohingyas in far-off Jammu and Ladakh, unceasing fascination for Sharia, insistence on the primacy of Islamic doctrine over national symbols and celebration of personalities like Jinnah and Aurangzeb shows Islamic sectarianism is alive and kicking. The hurt is compounded by intellectuals and academia telling Indians that Muslim rule unified, civilised and cultured India. Islamic iconoclasm and other excesses of Muslim invaders and rulers have been whitewashed with astonishing shamelessness.

Ayodhya movement had always been about correcting such distortions, exposing the dishonesty of establishment intellectuals, hypocrisy practised in the name of secularism, crass Muslim appeasement and restoration of native pride. A truthful reconciliation with India’s past is also the only way to achieve lasting Hindu Muslim unity. For all of it, Parliament, and not the courts deciding the issue as a mere title dispute, would be the proper forum. As far as the question of a temple preceding Babri Masjid at the site is concerned, neither of the two parties remains in doubt. Legislation passed by an elected government will not only be the expression of national will but a comprehensive redressal of Ayodhya dispute. It will be a resounding statement to mark justice and healing to the battered and bruised psyche of the nation. I would even suggest that the ordinance includes restoration of Kashi and Mathura temples at the original sites. These two temples are also of paramount importance for Hindus.