Ground Reports

Kodavas Have Held On To Kodagu Through Centuries, But Creeping Islamisation Of Region May Finally Break Them

Deviyani G

Mar 07, 2025, 01:00 PM | Updated Apr 02, 2025, 02:41 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Kodavas, sometimes known by the anglicised nomenclature- the ‘Coorgis’, have been undergoing turmoil and struggle for close to four centuries. From battling Tipu in the late 18th Century to more recently, asserting their identity amidst hostility with the Arebhashe Gowdas, their quest for self preservation seems to be an eternal one.

A month ago, perhaps for the very first time in this century, Karnataka witnessed the community coalesce (organically, one may add) in unprecedented numbers, for what many members term as a ‘peace march’.

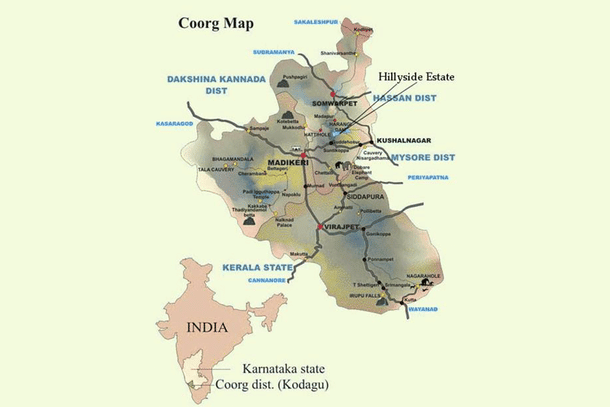

This cultural walk which started at Kutta and concluded at Madikeri, though immediately triggered by refusal of their entry into the Maha Mrityunjaya Temple in Kattemad, by members of the Arebhashe gowda community, soon transformed to be a show of strength.

The Kodvaamebalo (May the Kodava way of living, live on) march, was a call for unity; it was an assertion of indigenous pride—perhaps for the first time in forever, almost every Kodava was called upon to if not join the march itself, at least promote and facilitate it.

This reflects how the long-standing grievances of the community, after more than a century, are finally shifting from vague expressions to kernels of an organised campaign.

Who are the Kodavas?

Many legends surround the origins of the Kodavas. Folklore once fuelled rumours that they were descendants of Greek troops left behind by Alexander the Great. However, historical evidence suggests a different story. They are more likely an indigenous tribe from the hills of ‘Malyadri Sahyadri,’ nestled within Karnataka's dense forests.

Their native tongue is Kodava and their supreme goddess, Mother Kaveri—the life sustaining river that flows from the Brahmagiri hills at Talacauvery.

There have been several sub tribes within the Kodava community including-Kallera, Bollera, Mathanda/Kuduvanda, Buduvanda, Pandira, Pardanda, Porera, Paruvanda, Kallmadanda, and Ammandira. However, not all of them have survived to the present day. The main reason is a shortage of brides, which has led to their gradual absorption into other Kodava castes. Additionally, migration has further contributed to their decline.

Malevolence of Migration

Migration has been a cause for concern since time immemorial. It has slowly but determinedly wreaked havoc to the demography of the Kodagu.

Take for instance the Arebhashe gowda community itself. This community was brought in by the Lingayat Haleri Rajas of Kodagu, granted land and told to cultivate paddy and generate revenue.

“Post Tipu’s invasion, especially after his massacre of Kodavas in 1785 at Devattiparambhu, the Kodavas left their homes in North Kodagu (Bhagamandala and Talacavery) and shifted to interior regions such as Nalnad to escape the onslaught. Thereafter, the trusteeship of temples like the one at Kattemad were eventually taken over by the Arebhashe Gowdas, especially as a lot of these towns needed repopulation and the Haleri Rajas brought the Gowdas from Sullia to facilitate the same” says Roshan Somanna, the trustee of the non-profit organization Kodavaame.

Ironically, the traditional attire of the Arebhashe Gowdas (and for that matter most communities of Kodagu) themselves is not that different from that of the Kodavas. The Kodava traditional dress, known as Udupu, includes a half-sleeved, knee-length black wraparound coat, worn with a silk sash around the waist and a headgear, collectively called 'Kuppya Chele.'

The Arase Gowdas wear a similar outfit, but in white. However, unlike the Kodavas, they do not carry the peeche katthi, a silver knife that is part of the Kodava attire.

The Kodavas themselves wear the white version of the 'Kuppiya Chele' during weddings and sacred festivities and even death. The theory for the two toned change in attire is that the British, who came to Kodagu in 1834, brought along with them priests, who had issues with this attire. Since the white ‘kuppiya’ resembled the habit of Christian priests, the British passed an order to change the colour of the Kodava attire.

Then how come the Arase Gowdas still don white? "One theory is that often the Arebhashe Gowdas, who used to be managers in the plantations, were given the white Kuppiya of the plantation owner in recognition of the service rendered, once the current owner passed on. It was a matter of pride for them and they refused to give it up” Somanna states.

So given how intrinsically the two communities are connected both in culture and history, why the rift?

While recent hostility may stem from political tensions, the initial seeds of discord can be attributed to the British, after their arrival in 1834.

In 1837, the Sullia region witnessed an uprising against the British—the Amara Sullia freedom movement. This movement was predominantly led by the Arebhashe Gowdas while only a few Kodavas (predominantly those in the northern parts of Coorg) were said to have leant support.

Additionally, some Diwans from the Kodava community, who were retained by the British even after the Haleri Rajas were deposed, decided to support the colonisers. This divergence of allegiance marked the first instance of conflict between the two communities.

However, post independence, the communities have coexisted in relative harmony. In fact, members on both sides attest to the fact that these fault lines only erupted over the past 15 years or so, largely due to political motivations that thrive on dispute and divisions for relevance.

Manifestations of the growing rift became more evident when questions were raised by a member of the Arebhashe community on the centuries old right of the Kodavas to bear arms, without any license.

A petition was filed in 2015 in the Karnataka High Court, challenging the exemption under the Arms Act, 1959, questioning why such an exemption on the basis of ‘caste’ continues to exist.

Then came insults directed to prominent stalwarts of the community—Field Marshal Cariappa and General Thimayya and claims by the Kodavas that they were being restricted from conducting their sacred rituals during the Theerthodbhava (an event that marks the divine emergence of the River Kaveri from the Brahma Kundike). There are even intellectual property disputes over who can lay greater claim over the traditional jewellery native to the land.

Despite this, there is recognition between members of both communities that such incidents don’t have the sanction of the majority, and that there still exists a strong undercurrent of brotherhood that transcends isolated spurts of malevolence.

That is precisely why the Kodavamelo Balo march had no explicit mention of being against any one particular set of people but instead was actively marketed as the promotion of the Kodava spirit, love for their motherland and a campaign to seek greater protections for the preservation of their rights and culture.

A wise approach, one may argue, as the natives of Kodagu face a far more pressing existential threat, one that has already silently altered the region’s demography, language, culture, and even cuisine.

Waves of Migration

Coorg, with its verdant greenery, envy-inducing weather, fertile soil, generally hospitable people and profitable economic and agricultural opportunities, has played host to many waves of migration over the years.

The first wave began as a consequence of Tipu and his designs. Having attacked the Kodavas, he successfully converted a significant section of the population to Islam. These Kodava Mapilas faced ostracization back home. Since they no longer found brides within Coorg they had to resort to forging marriage alliances in Kerala. This marked the dawn of the Muslim Malayali migration.

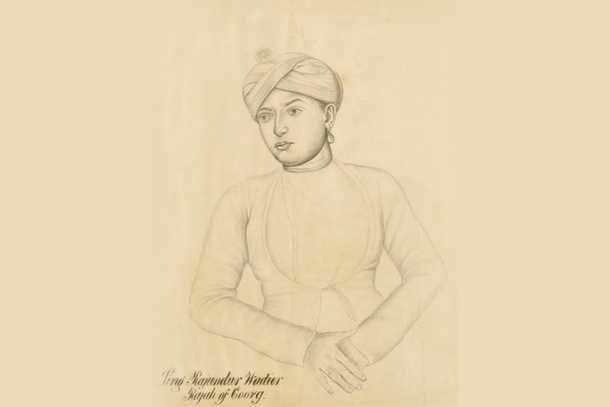

The next influx came post independence. Historically, Coorg was a separate kingdom ruled by the Haleri Kings for nearly 200 years, that is from the 17th century till the 19th century. The British deposed the Lingayat rulers and eventually Kodagu was categorized as a Part C state (a group that consisted of former Chief Comissioner’s provinces and princely states). This categorisation persisted till 1956.

In 1952, the first Vidhan Soudha elections were held in Coorgand the Congress emerged victorious. C.M Poonacha emerged as the Chief Minister from a legislative assembly of 24 MLAs.

Post this, in 1956, the state of Coorg was merged with the state of Mysore. It was now that the second influx of migration began, from both within Karnataka, such as the Mangalore region and also from states outside, such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

The migration from the Tulunadu region mainly consisted of workers for the paddy fields of Kodagu. They were followed by the Navithes Muslims - (Muslims of Arabic-Persian and Konkani origin) from the regions of Bhatkal and Karwar, who were followed by the Beyari Muslims again from the Mangalore region.

“The migration from Kerala was fuelled by labour issues, including lack of attractive wages or opportunities within God's own country. This influx mainly occurred from the lower levels of the economic table and thus it was the daily wage workers, carpenters, garage mechanics and welders amongst others who decided leave Kerala and call Kodagu home” notes Prathik Ponnana, a farmer and the state president of Karnataka Linguistic Minorities Association.

Agriculture aided this shift of abode. Pepper had begun to be grown extensively in Kodagu. During the blooming season, labour was needed to pluck the pepper from the pepper vines. The indigenous labour, while adept in dealing with harvesting coffee, lacked both the skill and knowledge to handle pepper, a void which was conveniently filled by the workers from Kerala who possessed this skill.

Same was the issue when it came to cultivation of ginger. As ginger picked up pace amongst the local planters as a lucrative commercial crop, paddy fields had to now be transformed into lands that can grow ginger—a labour intensive process that again created opportunities for workers from Kerala.

Since their migration in the 1950’s, the Kerala migrant community has gained a significant commercial foothold within the region. Having bought prime locations within the business districts of Kodagu, they went head-first into businesses such as stationary and grocery stores. As estate lands in Kodagu are still largely owned and controlled by the Coorgis and other Hindu communities, that remained the only available avenue. Likewise the Navithes decided to explore the textile business and prospered there.

How did this inflow of Malayali communities change Kodagu?

“When the 1952 census was conducted Kodava was the dominant language of the region, however most natives reported that they spoke Kannada until the late 70’s and 80’s as the Kodava language was then considered by many as a dialect of Kannada. Therefore, the results of the census gave Kannada the first place as the most spoken language, followed by Kodava. However, thanks to the migration from Kerala, the censuses that were conducted 20, 30 years later began to reflect the ‘unscientific’ growth of Malayalam” Ponnana notes.

“So today, when one speaks about the linguistic demography of Coorg, while Kannada remained the dominant language, Kodava was relegated to third place with Malayalam taking the second position. In fact, Malayalam is the only language that is growing at the phase it is at. At this rate, it is very likely to outstrip Kannada as well. If the migration had occurred in an organic and logical fashion, we would not have seen such unprecedented growth” he laments.

Another issue that this migration caused was that of religious conflict. “Most migrants from Kerala were Muslims. This meant with an increase in population, the region witnessed an increase in celebration of associated festivals, prayers and the bringing of Maulanas and Dharmagurus - all related celebrations and events are conducted in Malayalam, sometimes the language is even blared from loud speakers” Ponnana states.

The story does not end here. The most recent wave of migration, says Ponnana, that is aiding the existential crisis faced by the Kodavas is that of the Muslim migrants from Assam.

“In the recent years i.e. post 2011, Coorg has witnessed migrant workers who claim they have come from Assam but we strongly believe that claim is suspect. This is because the language spoken amongst them is not Assamese, it sounds more similar to east Bangla - thus they could very likely be illegal Rohingyas or other Bangladeshis” Ponnana laments.

Labour Mafia

The question now arises as to why there is a need for migrant labour in the first place, especially given the shift back to the cultivation of coffee and paddy. “This is because the indigenous labour in Coorg were the Yeravas- a tribal community that was engaged in daily wage labour; however due to a variety of reasons including, low fertility rate, lack of sufficient healthcare and rampant alcoholism, the community is at the verge of extinction.” Ponnana reveals.

He continues “Additionally, the second generation of the indigenous labour generally didn’t wish to engage in the profession and migrated to cities such as Mysore and Bengaluru. Greener pastures that were created thanks to the IT boom. This created a convenient vacuum in the agriculture sector that was filled by the Muslim migrants”.

Another Kodava planter, who wished to remain anonymous, did not mince words when it came to the reality of the conditions in which the indigenous labour had to work. “ Let me be blunt about it, the Coorgs were not very good in their treatment of labour, as much as I would have liked to have stated otherwise. The indigenous workers were not looked after well. Be it very low wages, at around Rs 10 a day during the 90’s, long working hours or abysmal housing, on all counts they should have been given a better deal”.

“However, (some of) this changed in the 1960’s when after the Coffee board was kicked out and the industry was liberalised, the planters were able to realise greater prices for their produce. This translated to fairer wages and better working conditions for the labour but by this time the indigenous labour had moved out and made way for migrants.” he states.

Today, while most of the Malayali labour have transitioned to business, the alleged Assamese have taken over. “As a planter, my primary goal during harvest season is to find labour to pick my Coffee, but the only labour available today to engage in this work are the Bangladeshis and these so-called Assamese, because the locals are no longer available. They have all moved to the cities, taken up better jobs to make more money.”

“Today we are paying this outside labour up to Rs 500-Rs 1000 per day. They come at 9 am and leave by 3 pm. Earlier labour used to come at 8 am and work all day till 5 pm. There is nothing we can do. Most of them don’t live on the estates in the labour quarters, they are housed elsewhere illegally. This whole mafia exists, where jeep drivers from Kerala bring them at the start of the day, drop them off at the estate and take them back in the evening. These drivers get a cut and commission both from the planters as well as the workers. So the Kodavas have effectively lost control over the labour market.” the planter reveals.

He continues: “For instance, now the picking season is going on and the Kodavas are ready to pay whatever is being demanded as otherwise we will face an acute labour shortage and incur heavy losses. We are essentially being blackmailed by the tight control of the labour mafia. There is no scope for mechanization when it comes to coffee. Picking still needs to be done by hand, especially given coffee is grown on slopes, it is not easy to run tractors or other vehicles”

“A corridor exists that runs from Chikkamangalur, Hassan, Coorg and finally into Kerala, which facilitates the movement of these Rohingyas from one place to the other, much like the underground railroads in the times of slave owning America. And all this has been possible because of the sanction and protection of the local Muslims.” he laments.

The Consequences

While in Karnataka, the language of the state is Kannada and receives both funding and regulatory protection, the Kodava language is not a beneficiary of the same. Though a minority language, it happens to be the dominant language that is spoken in the villages of Coorg, much more so than Kannada. The influx of Malayali migration however and their consequential dominance in business has now unfortunately replaced the Kodava as the language of business in Coorg.

“This is alarming, though in India, the Constitution under article 19 allows any citizen to move and settle anywhere within India, a prospect we are in agreement with. We also welcome the economic opportunities such migration facilities, it however, can not be at the cost of our own language. We are thus urging our people to not let go of Kodava. When they conduct business, they should do so in their mother tongue. This will expose people to the language and incentivise others to use it as well” Ponnana states.

Down the line, in about 10 to 15 years, there exists a very real possibility that Malayalam will even replace Kannada as the primary language of the region.

Another consequence of the migration is that there were originally 22 Kodava speaking communities in Coorg. These were inclusive of both SCs, STs and even OBCs, but due to the huge influx of migrants, their population was replaced. “Initially, the population of Kodagu was around 2- 2.5 lakhs, while now thanks to the migration the population has reached around 6.5 lakhs to 7 lakhs, we became minorities in our own land”

Apart from economic migration, political motivation also aided the flux. Vote bank politics played a huge role in this regard. It began during the times of the Congress Chief Minister Gundu Rao. In order to curry favour, cultivate vote banks and facilitate the sustenance of both the political party and the migrant population in the region, occupation of buffer zones was legalised.

Buffer zones along riverbanks are meant to remain untouched, with no construction or cultivation, as they are prone to flooding during heavy monsoons. This is precisely why the Kodavas have left these lands open and unused for generations.

This land became home to the new population. The Government of Karnataka post the merger of the Coorg surveyed these areas and designated them as government lands, and these lands were eventually granted to the landless migrants.

Subsequently, during the 2018 and 2019 monsoons, these very areas experienced flooding, landslides and loss of life, unlike the more interior estates that have traditionally belonged to the Kodavas.

“With the increase in migrant population, there has been an increase in threat to the biodiversity of the region as well. Forest lands and revenue lands which are meant to be left out in the interest of biodiversity and conservation were slowly encroached and once the migrant population became a sizable vote bank, the political class legalised the encroachment” Ponnanaa notes.

Food is another victim of demographic change. If one goes to any restaurant in Coorg in the last half decade, it will be easy to realize that Kodava food has been replaced by Malayali cuisine. In terms of dishes, the regional food of Kodagu was the kadambuttu (steamed rice dumplings) and pandi curry (pork curry). Due to religious dietary restrictions, pandi curry is slowly fading out of the picture.

“The government officials in Kodagu are corrupt”, Somanna notes. “The Kerala Muslims pay bribes that enable them to smuggle commodities. This way wood goes from Kodagu to Kerala while cows are transported to Kodagu from Kerala” he reveals.

However, all is not lost. “Culturally speaking, so far the 22 odd Kodava-speaking communities have held on to their traditions strong, thanks to which any mention of Coorg is still immediately associated with the Kodavas. This is also aided by the fact that migrants from the second generation onwards, though they speak Malayalam fluently, they only know how to converse and usually lack the knowledge of reading and writing as their education has been in Kannada medium government schools. This to an extent has helped in harmonisation between the two communities” Ponnana states.

Unfortunately, this strong Kodava spirit that has managed to preserve the native tradition and culture thus far faces another challenge—urban migration of the youth. Kodagu lacks quality colleges and universities, so the youth are forced to migrate to cities such as Mysore and Bengaluru post matriculation, and thereafter they proceed to greener pastures and rarely return to Coorg.

“We are thus urging the Kodava entrepreneurs to return to their homelands, invest in the region, generate enough employment to ensure the youth stay back and carry the legacy forward” Ponnana says enthusiastically.

The rural to urban migration within the community has consequences in terms of land ownership as well.

With the boom in tourism with Kodagu, and airports being just 50 kms away at Kerala (Kannur airport),140 kms away at Mangalore and 130 kms at Mysore, the draw of tourists to what is often termed as the Scotland of India is irresistible to both Indians and foreigners alike. Thus, the sector is attracting a lot of investment, primarily from Kerala (predominantly Kochi) and Hyderabad. The investment from outside the states outstrip that within Karnataka, and the expenditure is mainly directed at purchase of land and building of resorts.

“While now there is a growing social awareness amongst the Kodavas, who have realised that no matter what, the ties to their motherland should never be severed, those who had initially sold their land to outsiders are discovering that the new owners are again reselling the same land to more outsiders” Ponnana notes.

Thankfully, the recent boom in coffee rates helped incentivise Kodavas to retain their lands. “ The social security that our lands provide is the reason we have still been able to maintain a foothold in the region, otherwise we would have met fates similar to those of the Kashmiri Pandits or the Bodos” he states.

Way Forward

Ponnana notes that the total fertility rate of Coorg is 1.5. “Any rate below 2.3 means that a replacement population is unlikely to happen. 1.5 denotes the fertility rate of Coorg, the fertility rate of the Kodavas within this is likely to be even lower, so we do face the very real threat of extinction”

“The idea is to encourage Kodavas to have at least a minimum of 3 children if not more. This is especially important as the ‘Assamese’ migrant population in the region sometimes average 10 to 15 kids. They are already 30,000 in number. The first generation of migrants might have some connection with their own homelands and the urge to eventually return; the second generation onwards, those who are born here, would have much less of a draw back home. Therefore, this 1 is to 10 ratio is likely to change the demography of Coorg irreversibly.”

“Down the line, when India is celebrating a century of Independence, it is very likely that Kodagu might end up having an Assamese MLA. That is the harsh reality of the Kodavas are facing today.” Ponnana laments.

Initiatives are being taken by the community to combat this. For instance this January, the Kodava Samaj at T Shettigeri offered any couple having a third child almost Rs 1 lakh as an incentive.

One approach to preservation, Ponnana says, would be for the Kodavas to be granted similar constitutional safeguards like those in the northeastern states. “If we can be bestowed with the right to grant inner line permits (permissions required to enter particular regions, like in Nagaland), we will be able to track the migrants entering and leaving Kodagu.

"The district administration can then monitor how many days a migrant from Assam intends to stay here, and when they intend to leave. This way we can ensure that during the harvest season, the required labour can come, aid us in our agriculture, earn a decent wage on their end and then eventually go back. This way the impact on demography would be contained. Moreover, it would rescue the state from the responsibility of catering specifically to the migrant interest over that of the Kodavas as when they don't settle here, there won't be a chance for them to become a sizable vote bank”.

Additionally, the community has been demanding the Schedule Tribe status for quite sometime now and consequently the permission for the creation of autonomous hill councils. The plan is to have similar arrangements as that available to the inhabitants of Garo and Khasi hills of Meghalaya. This way the community can exercise greater control over the buying and selling of land within Kodagu.

Many Kodavas feel that the demand for a separate state is long past them. Demographically speaking, a separate state would only ensure that identity politics would play out. “The Chief Minister would likely be a Malayali and the Home Minister could end up being a Bangladeshi, therefore there is no point in demanding a state. A hill council is the best way forward. The council could consists members of the Kodava community and migrants who called Kodagu home before 1947 such as Amma Kodavas, the Heggades, the Arase Gowdas etc” Ponnana notes.

Ponnana then talks about linguistic safeguards “ It's time the Kodava language was included in the 8th schedule. When the Union government can grant Nepali and Sindhi, languages from outside India that status, why not Kodava - a micro minority language?”

Another way is to urge the state government to do more for the Kodava language and culture. “There are many states where even 12 languages have received official language recognition, such as West Bengal, 16 languages in Jharkhand, three in Telangana, so why is it hard for the Karnataka government to give official language status to the Kodava language?” Ponnana questions.

Ponnana even agrees to a concession stating: “The recognition could even be limited to just Coorg. Where the primary official language could be Kodava and the secondary official language could be Kannada”

Sacred Geography

The Kodavas are ancestor worshippers, they have a concept called the Ainmane which roughly translates to ancestral house. Every Kodava’s Ainmane is in Coorg.

They are firm believers that the spirit of their ancestors has mingled within the holy soil of Kodagu and no ritual or traditional worship of theirs is complete without an ode being paid to their holy mother Kaveri. The geography is sacred to them, their religion can not be divorced from it. Therefore, they must claim the soil as theirs.

Roshan Somanna recalls this popular saying in Kodava - Chatthangoo Petthaangoo Etthavu Kodavale Alla, that translates to 'if one does not go to lend support at the time of birth or death of a family member or a known person then a Kodava is not being true to his/her customs'. The land is divine, it is where their holy mother goddess Kaveri flows. No matter where they go in the world, they must return.

The Kodava story is a stark reminder of the delicate balance between progress and preservation. As Coorg grapples with the pressures of migration and modernisation, the community faces an existential crossroad.

The 'Kodavaamebalo' march was more than a protest; it was a plea for survival. Whether through inner line permits, Schedule Tribe status, or official language recognition, the Kodavas are demanding a voice in their own destiny. Their struggle raises a critical question: In an increasingly globalized India, can indigenous cultures thrive, or are they destined to fade into history?

The answer, it seems, lies not just in policy, but in the spirit of a people determined to keep their heritage alive, even as the sands of time—and the tides of migration—threaten to wash it away.