Science

Beyond The Numbers: Why ISRO's Low Launch Count Tells A Bigger Story

Karan Kamble

Sep 01, 2025, 11:51 AM | Updated Oct 09, 2025, 09:01 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

.jpg?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

There has been much chatter and chagrin in the media, both traditional and social, among the Indian space community. Enthusiasts, professionals, and policy nerds alike have criticised the Indian Space Research Organisation's (ISRO) slow launch cadence.

While the criticism on this count is valid, there's some nuance to better appreciate why ISRO launches have dropped off.

Broadly, several factors are at play, some of them strategic, some others beyond ISRO's control. But before we get into that…

ISRO's Launch Numbers

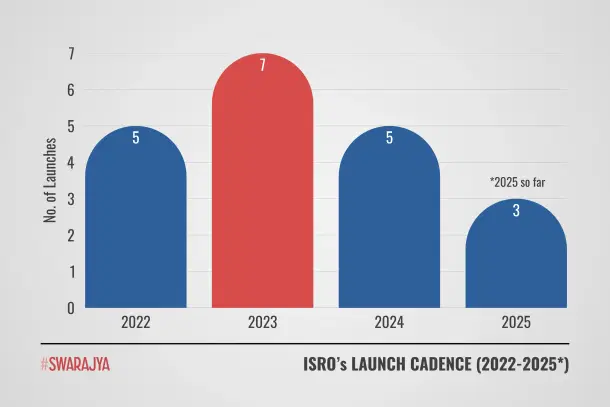

In 2025, and with nearly two-thirds of the year behind us, ISRO has managed three rocket launches. Of the three, one was a partial success (or a partial failure; half glass full or empty), and another was a failure. Not one of these was a commercial mission.

The one unquestionably successful launch was of the high-profile “NISAR” spacecraft. This stands for the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar Mission. ISRO's Geosynchronous Launch Vehicle (GSLV) Mk-II delivered the advanced Earth-observing orbiter to orbit flawlessly on 30 July.

The partial success was the previous GSLV mission (GSLV-F15/NVS-02), launched on 29 January. The rocket placed the spacecraft in an unintended orbit, and attempts to raise the orbit thereafter to the designated orbital location were unsuccessful due to technical difficulties. In ISRO's words, "the valves for admitting the oxidiser to fire the thrusters… did not open."

This was a high-stakes launch mission. A clean injection into the intended orbit would have firmed up India's "Navigation with Indian Constellation" (NavIC), introducing some essential redundancy into India's indigenous positioning and timing service. This is a regional equivalent of the United States' Global Positioning System (GPS), upon which most of the world depends for navigation.

As things stand today, the state of NAVIC is worrying, and India's long-term ambition to expand NavIC globally has taken a knock.

The failed 18 May launch mission concerned ISRO's workhorse rocket, the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). A new satellite in India's longstanding "EOS" Earth Observation Satellite series (EOS-09) lifted off, but the rocket failed to deploy the satellite into the planned Sun Synchronous Polar Orbit (SSPO). This was PSLV-C61, which aborted due to a chamber-pressure anomaly in the third stage.

In 2024, ISRO's launch cadence was slightly better, with close to half a dozen launches, including GSLV-F14 (INSAT-3DS), SSLV-D3, and PSLV-C60 (SpaDex). Still, this was well short of the double-digit missions that had been planned.

Therefore, the last couple of years, and we are three-fourths into the current one, have seen a total of just eight launches.

That's a very low count, especially considering that four launch vehicles are available: the GSLV Mk-II, the PSLV, the Launch Vehicle Mark 3 (LVM3), and the Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV).

Yet these vehicles are not production-friendly in the way modern industrial rockets are. PSLV and GSLV, in particular, were designed decades ago and rely on semi-handcrafted assembly. They cannot simply be rolled off a line the way SpaceX mass-produces Falcon 9 boosters.

For comparison, though unfair, the US has carried out over 100 launches, China close to 50, and Russia in double digits just this year. The unfairness lies in structure. SpaceX alone accounts for nearly 90 per cent of US launches. China's launch rhythm is underwritten by its military-industrial complex. Russia, even under wartime sanctions, operates assembly lines for Soyuz rockets that have been perfected over decades.

India's system, by contrast, is still transitioning from state-led, hand-built rockets to industry-driven, scalable production.

Coming on the heels of a landmark year in 2023, when ISRO corrected the Chandrayaan-2 wrongs of 2019 to nail the landing of a spacecraft on the surface of the Moon in the south pole region, no less, and accomplish all mission objectives, ISRO has understandably struggled to sustain the jubilation.

Planned big-ticket launches are thinly spread across calendar years, and the uncertainty of anomaly investigations, supply-chain delays, and shifting institutional priorities are now baked into timelines.

It must be said that the low launch count was not part of the plan. The target was 30 space launches between January 2024 and March 2025. Only seven launches were executed during this period.

So, yes, the launch cadence is certainly down and calls for constructive criticism. But scientists and engineers connected with ISRO and the wider space technology ecosystem have some perspective to offer.

Why The Launch Slowdown

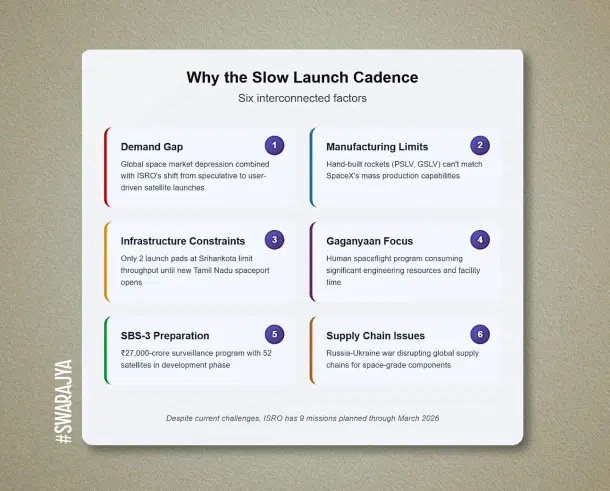

Broadly speaking, ISRO's slow launch cadence can be boiled down to six interlinked factors:

- a lack of launch demand combined with a change in ISRO's satellite procurement strategy;

- industry and manufacturing bottlenecks;

- the physical limits of launch infrastructure;

- the diversion of resources into the human spaceflight programme;

- preparation for the massive SBS-3 surveillance programme;

- and global supply-chain disruptions.

First up is the issue of demand. "Launches have gone down; the only meaning is that there is no demand for the (launch) vehicle," a space-tech engineer at a prominent startup who did not want to be named told Swarajya.

This is a view expressed even by then-ISRO chairman, S Somanath, last year. The global space market was "depressed," he said in June 2024, while clarifying the misconception that "people will come" if you "build low-cost rockets." India's launch capabilities are "three times the demand," he added.

"We are not able to use our capacity because satellites are not there. At ISRO, we have PSLVs, but we have no demand. Rockets are built and kept in stock, but not finding customers." He prescribed the creation of an "internal demand and market" rather than "waiting on American satellites to come."

What doesn't help the demand equation is that Indian rockets lack cost-competitiveness compared to those of Elon Musk's SpaceX. Falcon 9 has long been the benchmark, offering roughly $2,600/kg to low-Earth orbit with reuse. PSLV and GSLV, smaller and expendable, cannot compete at that level. Perhaps that explains why even Indian startups have chosen to fly SpaceX on multiple occasions.

A year since, Somanath has said Indian rockets are in great demand, but the country is falling short of manufacturing capacity. “Indian rockets are in great demand. But the problem is availability; it’s controlled (constrained?) by our ability to manufacture in numbers,” he noted.

PSLV and GSLV were never designed for bulk production, and their current configuration doesn't offer much room for cost-cutting modifications. For production-friendliness, ISRO will have to rely on its newest rockets, LVM3 and SSLV, and eventually the New Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV).

Pawan Goenka, chairman of IN-SPACe, has revealed that India has approval to build 60-plus LVM3 rockets with private industry taking the lead, but this industrial ramp-up will take time.

The demand question is intertwined with ISRO's new procurement philosophy. Earlier, satellites were launched speculatively. Build it first, see who uses it later. Now, launches are user-driven: a ministry or customer must commit before ISRO proceeds. This avoids waste but naturally suppresses launch counts in the short run.

Private companies have a big role to play. More than 350 space startups now exist in India. Even if a fraction begins building and flying satellites, launch cadence could accelerate dramatically.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has set an ambitious goal: "At present, we witness about five to six major launches annually from Indian soil. I would like the private sector to take the lead so that in the next five years we reach a stage where we launch 50 rockets every year, one every week." That scale-up is only feasible if industry industrialises SSLV and LVM3 production.

Meanwhile, ISRO is focusing its energies on core research and development, from reusable launch vehicles and semi-cryogenic engines to electric propulsion, and big-ticket projects such as Gaganyaan, Chandrayaan-4, and the Bharatiya Antariksh Station, with the long-term ambition of landing an Indian on the Moon by 2040.

Another focus is the nearly-Rs 27,000-crore SBS-3 programme, led by the Defence Space Agency, which will see 52 surveillance satellites launched over the next five years. ISRO will build 21 satellites, and industry 31. Preparing this constellation is naturally consuming resources before the launches begin, but once the satellites are ready, the cadence is expected to shoot up, likely starting next year.

Then there is perhaps the biggest factor: Gaganyaan. ISRO is progressing towards its first uncrewed test flight with the humanoid robot Vyommitra in December 2025. The full crewed mission is planned for 2028. Human spaceflight demands intense engineering focus, range scheduling, and pad time. Even one abort-test vehicle ties up months of facilities and personnel.

Compounding this are infrastructure limits. ISRO currently operates from two launch pads at Sriharikota. Pad turnaround time, integration, and refurbishment mean that throughput is inherently capped. Relief will only come once the new spaceport at Kulasekarapattinam in Tamil Nadu, designed for smallsat launches, becomes operational later this decade. This new spaceport could witness 20-25 launches every year.

And finally, the broader environment. The Russia-Ukraine war and rising geopolitical tensions have disrupted global supply chains for space-grade electronics, alloys, and cryogenic components. ISRO has managed relatively well, but delays creep in.

Upcoming Launches

Looking ahead, ISRO has nine missions lined up from approximately this month through March 2026. Every rocket in its arsenal will be called upon to execute these missions, which include the GSLV launch of the NVS-03 to bolster NavIC, the PSLV launch of the Oceansat-3A, the LVM3 launch of a US communication satellite called Block-2 BlueBird, and the Gaganyaan-G1.

The first tranche of SBS-3 launches might follow not long after. Chandrayaan-4, a possible lunar sample-return, and preparatory work on the Bharatiya Antariksh Station are on the horizon.

This suggests that we might now just be in the lull before the lift-off.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.