Science

Darwin, Science And Dharma

Aravindan Neelakandan

Feb 12, 2018, 06:51 PM | Updated 06:51 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Charles Darwin is to biological sciences what Albert Einstein is to physics. Perhaps even more. He changed the place of humanity forever in the biocosm.

Before Darwin, despite the Copernican revolution, somehow the human being was seen as the pinnacle of creation. The special place that Earth lost in the universe was accorded by biology. Darwin changed that.

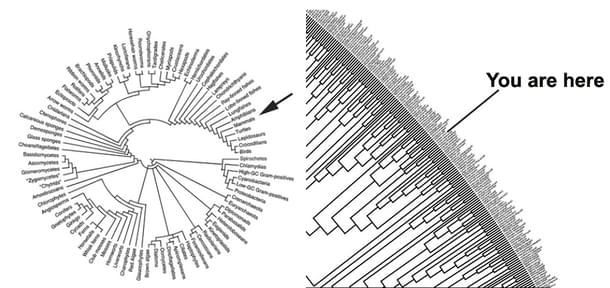

Natural selection – the combined dance of self-replication and changes in the environment and selection – inevitably led to the conclusion of a common origin for all life. There was neither special creation nor a ladder but only branching. Every species became a branch in the big tree of life – the phylogenetic tree.

Each branch in this tree was seen as best suited in its own way to optimise its growth. Then, a change in the external environment adversely affected what was once seen as “best suited” for growth, causing the existing branch to wither away and new branches to sprout in different directions.

All branches, however distantly placed, are all connected by a common phylogenetic thread. In the case of planet Earth, that thread, which is innate in all beings and can self-replicate and modify through variations, is the famous double-helical DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid.

However, that discovery would come later. And in that lay also the weakness of Darwin’s theory originally.

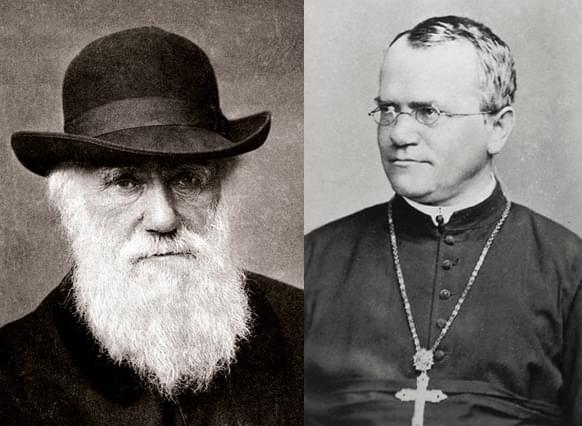

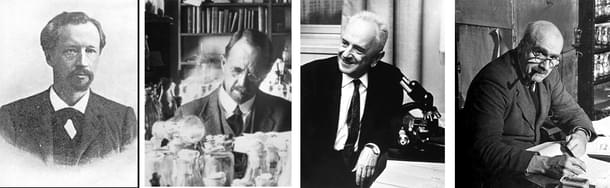

Darwin believed in the inheritance of acquired variations. He thought that natural selection worked on the observable small variations he noticed in populations. But not all such variations were inherited. Nor did Darwin know the process through which heredity worked. It was Gregor Mendel (1822-1884), an Austrian priest, who discovered the laws of genetics. In fact, Mendelian laws, now famous, showed how the genetic mechanisms passed the traits on to populations.

Darwin himself was interested in how the populations changed over a period of time and evolved into new species. He had correctly arrived at the process. However, the locus of the production and inheritance of variations on which selection process worked, remained a mystery. It was a botanist, Hugo Marie de Vries (1848-1935), who came up with the concept of genes and suggested the theory of mutation. It was geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866-1945) who worked on fruit flies; he showed how Darwinian selection operated on Mendelian variations.

To cut the long story short, Darwin’s theory became even more scientific with Mendelian genetics, jettisoning Darwin’s own belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

The synthesis of Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics shows how science differs from dogma.

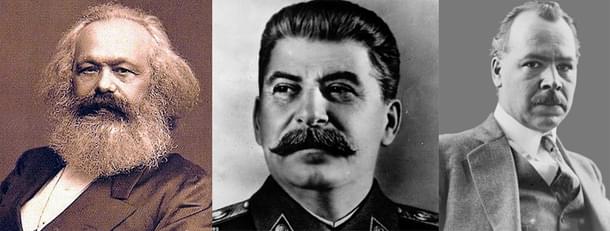

Consider Marxism. It claims it is a science. However, each time a scientific discovery was made that the commissars believed was against dialectical materialism, the Marxists branded the theory as “bourgeois”, reactionary and decadent. Then they used the power of the state and propaganda to run an inquisition.

Karl Marx, who initially considered Darwin’s theory favourably, later became critical of it because it did not seem to serve his ideological speculation. In 1861, he wrote of Darwin’s work as “most important” because it “suits my purpose in that it provides a basis in natural science for the historical class struggle”. However by 1866, Marx had come to the conclusion that Darwin had been superseded by Pierre Trémaux, a French orientalist and architect whom Marx considered as “far more significant and pregnant than Darwin”. He also approvingly wrote that the conclusion of Trémaux “shows that the common negro type is only a degeneration of a far higher one”.

The Marxist state would go even further. It saw Mendelian genetics as a bourgeois conspiracy and ran a ruthless inquisition against geneticists promoting the pseudoscience of Lysenko. The death of geneticist Nikolai Vavilov in a Stalinist prison is the twentieth-century replay of Galileo’s imprisonment and Bruno’s execution combined in one by the Marxist state. Vavilov’s martyrdom deserves a better memory than what it gets today.

Now let us consider Darwinian scientists behaving like Marxists. They could have said that Mendelian genetics was a Catholic assault on Darwinian theory. The way Darwinian science was receptive to Mendelian genetics and thus enriched itself, shows the power of being open to truth – a quality Swami Vivekananda wanted religion also to have.

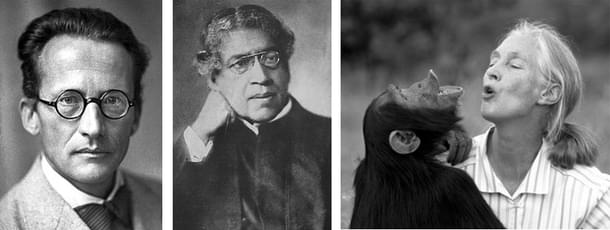

When Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger started working on the problem of what is life, the genetic material being complementary to the seemingly opposite aspects of stability and variation became important to him. He took it to a fundamental level and asked:

Consciousness is never experienced in the plural, only in the singular. ... How does the idea of plurality (so emphatically opposed by the Upanishad writers) arise at all? ... Now there is a great plurality of similar bodies. Hence the pluralization of consciousnesses or minds seems a very suggestive hypothesis. Probably all simple, ingenuous people, as well as the great majority of Western philosophers, have accepted it. ...The only possible alternative is simply to keep to the immediate experience that consciousness is a singular of which the plural is unknown; that there is only one thing and that what seems to be a plurality is merely a series of different aspects of this one thing...

It can be seen that Schrödinger arrives at this premise as a Vedantist. However, he is also repeating here a Darwinian insight of one life branching into many. What Darwin witnessed at the species level, Schrödinger expands to a deeper aspect of reality – consciousness experiencing plurality.

One wonders if natural selection is very much an archetypal process inherent in the realm of “Maya” and by comprehending it one can see beyond the appearances into the connecting reality. The vision of the “One” in all diversity is also declared by Jagadish Chandra Bose when he declared at the end of demonstrating the blurriness of the barriers between life and non-life, plants and animals:

They who behold the One, in all the changing manifoldness of the universe, unto them belongs the eternal truth, unto none else, unto none else.

After all, does not Krishna in Bhagavad Gita point out that the Truth belongs to those who experience the One in many and perceive in many, the One (13:30)?

This Darwinian and Vedantic vision has serious ethical implications and it is not social Darwinism in the least. The Isavasya Upanishad points out that the person who experiences the One in the many can never hate another (2:6).

If you have doubts as to whether Darwinian discovery can induce such trans-species empathy, see Jane Goodall.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.