Science

New Research Shows Sanskrit Evolved BEFORE The Indus Valley Civilization

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Jul 30, 2023, 02:03 PM | Updated 02:03 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

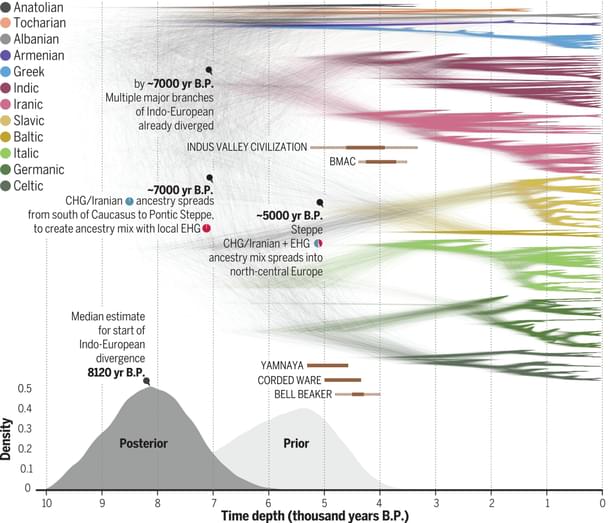

A new study on the origin of Indo-European languages, released by Science magazine this month, integrates linguistic and genetic research to infer that early forms of Greek and Sanskrit began to evolve as independent language branches from before 7000 years ago.

That is two to three millennia earlier than the conventional date of 5000 years ascribed by most historical research of the past century.

The study also suggests that the common origin point of the Indo-European languages may have to be shifted from its hitherto-accepted standard location in the steppes of Southern Russia, to somewhere in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East – an arc stretching from Israel through Syria to Iran.

These findings contradict some established historical notions which have rarely made sense to Indian scholars, as well as generally accepted views on Eurasia’s prehistory. Their implications are both numerous and fascinating.

A little background first.

Historical scholarship of the colonial era generated three patent absurdities which, for various reasons, still command rigid adherence in most academic circles in one form or another:

One, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC, or the Sindhu-Saraswati culture as it is more commonly termed today), which emerged, flourished, and declined between 5000 to 3500 years ago, was socio-culturally distinct from our Indic Sanskrit-based culture.

Two, the IVC was comprehensively supplanted by an invasion of Sanskrit speakers (called Aryans, or those who spoke ‘the noble tongue’) from somewhere in the steppes of southern Russia around 3500 years ago.

Three, the sacred texts of these steppe-Aryan invaders, the Vedas, were composed and compiled at the fag-end of their long journey to the subcontinent around 3500 years ago. This date of 1500 BCE was arbitrarily set in stone by Max Muller, a German Indologist.

None of these ‘theories’ have any factual basis or historical evidence. However, in the process, these colonial historians discovered strong similarities between Sanskrit and Ancient Greek first, and then with the younger Old Latin. That meant all three tongues had evolved from a common ancestral language.

One example of a term cognate (meaning, sharing a common origin) to Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, is: the deity Jupiter in Latin is equal to Zeus Pater in Greek, and Dyaus Pitr in Sanskrit.

They also unearthed deep linguistic ties between Sanskrit and Avestan (an extinct form of Old Persian in which the Zoroastrian sacred text, the Zend Avesta, is written). For example, Soma of the Vedas is Haoma in the Avesta; and Ahura is cognate with Asura.

In the absence of any epigraphical evidence older than 3000 years for any of these languages, scholars clubbed their antecedents into a hypothetical root language which they called ‘Proto-Indo European’ (PIE).

That solved a lot of problems and warded off uncomfortable questions. Now, Sanskrit-speaking Aryans could migrate from the steppes of Russia, invade the subcontinent, destroy the culture of the Indus valley (which conveniently spoke no Sanskrit since the Indus script remains undeciphered), establish their own high culture, compose marvels like the Upanishads – all well after 1500 BCE, and introduce the horse to India.

It also ‘solved’ the Mitanni contradiction: engraved tablets dating to about 1400 BCE, and discovered near the Syrian-Turkish border, which record invocations to Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and the Nasatyas, by a king named Tushratta (Tvesharatha – one with a charging chariot; or Dasharatha). By the PIE hypothesis, there was now no need to somehow try and link Tushratta with India, since his forebears were but one of many groups which migrated out of the Russian steppes, just like others who left for India or Iran.

Unfortunately, the three absurdities, coupled with the PIE, condense Indian prehistory into an unacceptably-brief timespan. By it, Videgha Madhava of the Shatapatha Brahmana moves east to clear the dense forests of the eastern Gangetic plains and establishes the kingdom of Videha (Mithila) only around 1000 BCE. This is followed at a frenetic pace by the mushrooming of countless pastoral communities, organized farming, trade, trade routes, administrative machineries, the rise and fall of dynasties in multiple kingdoms, and the evolution of great cities like Kashi or Vaishali with long histories of their own.

And all of this is supposed to have happened in not just a few short centuries, and so comprehensively across such a vast region, but some centuries before the era of Bimbisara, the Buddha, and Mahavira, because, lest we forget, historical records exist in that region from around 600 BCE onwards.

But scholars struggled to question such contradictions because they had no evidence to disprove this appealing PIE hypothesis based solely on linguistics. That is where the findings of the new study come in.

Caveat emptor: while the study has numerous limitations, makes many assumptions, and lacks definitive boundary controls, it is a rigorous probabilistic assessment which is a step forward from the selective speculations which have bedevilled this field for a century.

First, the study posits that Sanskrit and Greek diverged into separate branches 8000 years ago. This is at the tail of the first global agricultural revolution, when organized farming and the domestication of animals led to the growth of permanent settlements.

It means that some sort of Sanskrit, plus its derivatives, was being spoken in villages, and, was the lingua franca for a large region, over 4000 years before Max Muller’s arbitrarily-fixed date of the Vedas’ composition.

Second, the study shows that the Sanskrit and Avestan-Persian languages branched over 5500 years ago, and went on to develop as separate family trees with almost no subsequent interaction. This is significant.

Bearing in mind the close lexical similarities between Sanskrit and Avestan, the even closer grammatical resemblances, and restricted linguistic exchanges thereafter, this finding pushes the composition dates of both the Vedas and the Zend Avesta back by at least two millennia.

Third, the study clearly shows that Sanskrit had an influence on the development of Greek, almost continuously, till around 2000 years ago (zoom into chart to track lines leading from the Sanskrit language tree to the Greek one). This not only predates the hypothetical PIE language, postulated to have evolved about 5000 years ago, but essentially negates it as well.

Fourth, a branching date between Sanskrit and Greek of 8000 years ago predates the supposed movement of Aryans from the Russian steppes via Iran to India by at least 4000 years, and effectively negates that hypothesis. This is reiterated by a branching date of 5500 years ago, between Sanskrit and Avestan, which too, predates the Aryan invasion hypothesis by two millennia.

In simple English: it is not possible for a people to have brought a proto language to a region when branches of that proto language had already separated, and begun to evolve independently in that very region, much earlier. It would be less absurd to say that Tamilians introduced the rasgulla to Bengal in the 1960s!

In addition, and rather significantly, the study’s integration of genetics and linguistics concludes that the hypothesis of a Russian homeland for the Aryans is untenable. The authors, instead, place the origins of PIE speakers ‘somewhere’ in the Middle East.

Fifth, the study dates the origins of Pali as a separate language branch to almost 4000 years ago. The implications are staggering. If true, this means that Pali, the language of Magadha, and the language in which the first Buddhist canons were recorded, was alive and in use, in India, during the Indus valley period.

Sixth, equally significantly, the study shows that Vedic Sanskrit (and the authors have used that term with purpose) predates the rise of the Indus Valley civilization, which means that the Vedas were composed well before the Great Bath of Mohenjo Daro was built. This also means that the Vedas predate the Bronze Age.

There is more in the study, but just these six observations are enough to show that the old, entrenched colonial hypotheses were no more than rank speculations completely off the mark. Instead, this study reinforces historical research which shows that the Indus Valley civilization was a very Indic one.

Of course, true believers will hold on to their pet Aryan invasion theory by invoking the ‘horse problem’ – the archaeological fact that the horse was introduced into the Indian subcontinent only around 3500-4000 years ago.

There is no problem. There was brisk trade between the Indus Valley and the Middle East from as far back as 4500 years ago, both overland and maritime. And just as a Dubai-return would bring a VCR home from the Middle East in the 1980s, someone first brought a horse back many millennia ago. There is no need to wear oneself out with convoluted thinking. The point is simple: the Aryans didn’t bring the horse to India – they brought it back home.

And the Mitanni inscriptions? If Singapore could have a president named Devan Nair, and Suriname a president named Chandrikapersad "Chan" Santokhi, then the Mittani would very well have had a king named Tushratta.

Thus, in conclusion, it is an interesting study which debunks hoary colonial myths. It may be taken as a scientific step in agreeing that the homeland of the Aryans is closer to home than earlier speculated, and, that the Vedas are a lot, lot older than we think.

Perhaps, in time, through more similar, rigorous studies, an Aryan Invasion Theory, which was quietly rebranded as an Aryan Migration Theory (just like global warming was rebranded as climate change), may be supplanted by an Aryan Exodus Theory from the subcontinent.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.