Science

SUITing Up Aditya: How This Instrument On India’s Maiden Solar Space Mission Will Advance Sun Science

Karan Kamble

Sep 04, 2022, 06:41 PM | Updated Sep 05, 2022, 12:50 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

India’s first space-based mission to study the Sun, called Aditya-L1, is expected to take off early 2023.

The multi-wavelength solar observatory in space — to be in a halo orbit around Lagrangian point 1 of the Sun-Earth system, 1.5 million kilometres away — aims to provide continuous coverage of the Sun’s atmosphere in various wavelengths of light. Mission life is expected to be five years or more.

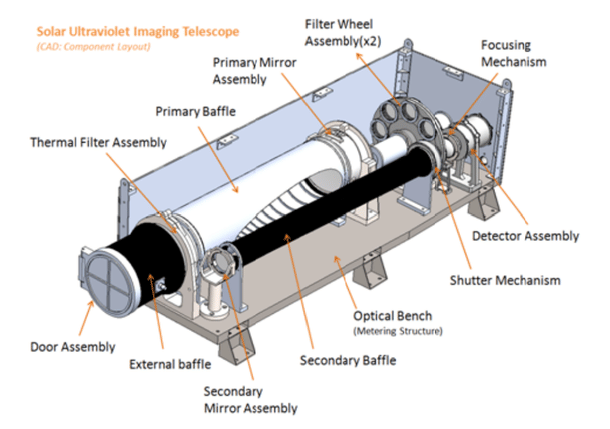

Seven payloads on the spacecraft will help scientists obtain a comprehensive picture of the Sun. One of the key payloads is the Solar Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (SUIT).

The telescope is primarily developed at the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA, Pune).

Collaborating institutes include the Center of Excellence in Space Sciences India at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (Kolkata), the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (Bengaluru), the Physical Research Laboratory (Ahmedabad), Manipal University, as well as the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

SUIT will study the radiation emitted by the Sun in the near-ultraviolet wavelength range of 200-400 nanometres (nm). It will provide near-simultaneous observations of lower and middle layers of the solar atmosphere, namely the photosphere and chromosphere.

This will open up a new, unprecedented window to the Sun because full-disk images of our star have not been taken in this wavelength range from space thus far.

SUIT was reviewed just last month at the UR Rao Satellite Centre (URSC) in Bengaluru. Swarajya reached out to the principal investigators of the SUIT instrument, Professor A N Ramaprakash (IUCAA) and Professor Durgesh Tripathi (IUCAA), to learn about this key Aditya-L1 payload, including its making, progress, and scientific possibilities.

You were in Bengaluru (at URSC) on 9 August along with the URSC Director and ISRO Chairman reviewing the progress of SUIT. Was there anything in particular regarding SUIT that was under review? And what was the consensus view after the meeting?

Indeed, the complete SUIT team was in Bengaluru. In fact, most of the SUIT team is stationed in Bengaluru working round the clock, as the payload is going through the final phases of integration and testing.

That day was special as the Chairman wanted to take a look at the assembled payload. It was not related to any review as such, but since the Chairman was at the ISITE campus for some other work, he wanted to see the progress himself and also provide encouragement and support to the team.

Initially, the mission timeline was a severe constraint in developing and delivering SUIT. But with the launch date having moved ahead by years, how did the stretched timeline affect the initial constraints, if at all?

We do not think that this is the right way to put it. We must note that we are developing a payload that will fly to the L1 point, which is 1.5 million kilometres towards the Sun, with the aim that it will study the Sun 24X7 for a minimum time of five years, if not more. This is the first time such a payload is being developed worldwide.

We should remember that space is very unforgiving. One wrong decision during the design phase or one misstep during the assembly and testing could have catastrophic effects. Therefore, qualifying a unique payload like SUIT for space has to follow a strict process of checks and counter checks.

Each and every component has to go through various procedures to make sure that they survive the harsh environment in space. Special ultra-clean room facilities had to be set up where the payload is being integrated and tested. We are thankful to ISRO for their understanding and supporting us all through.

Was it an engineering challenge to develop SUIT? Say, for instance, in developing the thermal filter?

Indeed, anything that has to be done for the first time has its own challenges. SUIT also had its challenges.

As you mentioned, the thermal filter is one of the most crucial parts of the payload that blocks the unwanted light and heat from entering the payload. We have developed that entirely indigenously in collaboration with Luma Optics.

Also, if you recall, SUIT will observe the Sun at 200-400 nm, and the solar flux in this passband changes by a factor of 18-20. We have 11 different filters in the pass band. It would have been best to have 11 different telescopes for each filter, but you can imagine the cost of such a project.

We have 11 filters on a single telescope with a single detector with a predefined dynamic range. Therefore, getting the fluxes from each filter within the detector's dynamic range has been another challenge. We also have a number of moving mechanisms on board for opening and closing the door, focussing and defocussing, exposure control, etc.

On top of that, we have inbuilt intelligence on board to detect solar flares. Note that studying flares is one of the primary goals of SUIT. However, we cannot predict when and where a flare will take place on the Sun. Therefore, it was essential to develop onboard intelligence that continuously monitors the Sun in one of the channels, detects flares automatically, and gets into flare mode of observation when that happens.

What does SUIT open up for us, after Aditya goes to its new home hopefully early next year, in terms of better understanding our Sun?

SUIT will observe the Sun in the 200-400 nm wavelength range. It provides observations of the Sun's Photosphere and Chromosphere in UV. This has not been done from space so far. There have been some attempts in the past, but the wavelength range was limited and only a tiny area of the solar disc was studied. SUIT will study the full disk. The beauty of SUIT is that it kills two birds with one arrow.

It also provides data crucial for understanding the dynamic coupling of the magnetised solar atmosphere. It provides a new window to study mass and energy flow in the solar atmosphere. It will help us measure and monitor the spatially resolved solar spectral irradiance in the NUV (near-ultraviolet), which is essential to understanding the relationship between the Sun and climate on Earth.

Are there any other solar probes that would combine well with SUIT to broaden the picture for us?

Indeed, there are several such missions; for example, the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) and Heliospheric Magnetic Imager (HMI) onboard NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), the Interface Regions Imaging Spectrometer (IRIS), and Solar Orbiter. SUIT will provide data in the wavelength range not covered entirely by these probes.

How do we plan to open up SUIT data to potential collaborators worldwide in order to diversify expertise and investigation?

There is a data policy document that ISRO is finalising. However, collaboration with any scientist is always possible through the principal investigators.

Does SUIT benefit from launching up in the solar neighbourhood as we approach the peak of the Solar Cycle 25? Or is it cycle phase-agnostic?

Sure, it would be helpful. As we mentioned earlier, one of the goals is to monitor the spatially resolved solar spectral irradiance of the Sun. Therefore, it is important that we can monitor for at least half of the cycle.

You went to the IAUGA 2022 in Busan, Korea, and delivered two invited talks — could you briefly highlight the takeaways or overall message of the talks?

Yes, I gave one talk at the IAU symposium on "The Era of Multi-messenger Solar Physics" and another on the Division day of Solar and Heliospheric Physics. These talks were on the whole Aditya-L1 mission science and not only SUIT-specific.

Both the talks were well received. There were questions related to the timelines on the data release to the international community and so on. The questions revealed that there is great interest in the international community about the data and insights which the payloads on the Aditya-L1 mission will provide.

You said the talks "created tremendous interest." What stoked the interest of the global solar community?

The uniqueness of the set of observations that Aditya-L1 will provide. Unprecedented combination of spectral and temporal coverage and observational cadence that SUIT offers will make really new science on solar atmospheric energy dynamics.

So, SUIT is looking good for the Aditya-L1 launch in 2023?

Indeed, so far, so good. Nevertheless, bear in mind that it is a very challenging payload to build, but we have put together a very talented team to deliver it.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.