World

How USAID's Quest To “PREDICT” Pandemics May Have Caused One

Prasenjit Ray

Feb 15, 2025, 01:06 PM | Updated Feb 17, 2025, 10:30 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

![USAID funds went to the Wuhan Institute of Virology (Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash [coronavirus visualisation] and the USAID logo)](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-02-15/5h28t930/USAID-and-Covid-19.png?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

![USAID funds went to the Wuhan Institute of Virology (Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash [coronavirus visualisation] and the USAID logo)](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-02-15/5h28t930/USAID-and-Covid-19.png?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

USAID, the United States Agency for International Development, has recently found itself at the centre of growing controversy under the Trump administration.

Elon Musk, head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), has publicly denounced USAID, calling it a “criminal organization.” Trump accused it of being run by “radical lunatics,” demanding it to be shut down.

Critics are raising serious questions about how the agency spent taxpayer money and whether some of its activities might have actually worked against both US interests and the countries it was meant to help.

The agency has faced accusations of inefficiency, corruption, waste, and abuse, with some arguing that USAID has become a tool for pushing a left-wing political agenda. New revelations are emerging almost daily, exposing how the agency ended up serving ideological goals..

What is USAID?

For those not familiar, USAID is a gigantic bureaucracy, which employs over 10,000 people, two-thirds of whom work outside the US. Formed in 1961, during the Cold War, under President John F Kennedy’s executive order, the agency has long been viewed as an extended foreign policy arm of the US. It now manages a budget of nearly half a trillion dollars annually.

Over the years, USAID has been repeatedly accused of using “development aid” to meddle in other countries' affairs and influence political changes in countries deemed unfriendly to US interests.

A notable example occurred in 2014, when USAID funded the development of a Twitter-like platform designed to spark dissent in Cuba. Similarly, USAID has been linked to pro-American regime change efforts in Venezuela, Ukraine, Brazil, Nicaragua, and many other countries.

USAID's partnerships have also drawn scrutiny, particularly its collaboration with organisations like George Soros' Open Society Foundation, which many see as a subversive organisation orchestrating influence campaigns worldwide.

USAID’s "development aid" is also believed to have ended up in the pockets of terrorist groups like al-Qaeda, Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Taliban, and Hamas.

But perhaps the most damning example is USAID’s funding of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), a facility at the centre of the debate over the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Federal records show that USAID provided over $54 million in grants to EcoHealth Alliance through its PREDICT programme, making it the organisation's largest US government funder.

EcoHealth Alliance then funnelled millions to the WIV, leading to calls for an investigation into whether USAID inadvertently helped spark the pandemic it was supposed to “PREDICT.”

USAID PREDICT and Wuhan Institute

USAID, through its PREDICT project, aimed to identify viruses with pandemic potential by collecting samples from animals in wildlife hotspots worldwide.

The project was part of the Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) programme, which started in 2009 by USAID through its partner, the University of California, Davis. It was the “largest virus hunting effort” anywhere in the world, and it ended in 2019, the same year the Covid-19 pandemic began to spread globally.

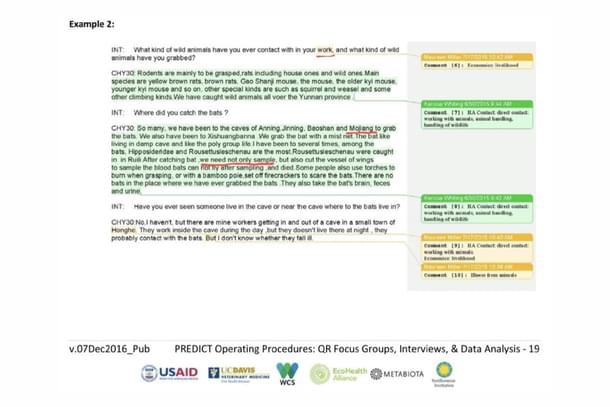

In the 10 years that it was in operation, PREDICT conducted extensive surveillance into coronaviruses in bats and worked closely with the WIV in regions of southern China and neighbouring regions of Asia, which were considered "hot zone" regions for emerging pandemics.

The ultimate goal of the PREDICT project was to discover viruses that could potentially spill over from animals to humans, offering an early warning for future pandemics.

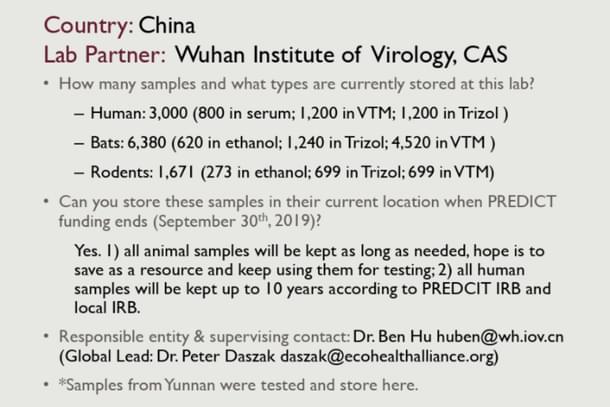

Public data reveals that PREDICT collected 11,051 samples, including 6,380 from bats, which were then stored at the WIV for further study.

The programme was supposed to use both experimental and modelling approaches to assess the potential for these viruses to spill over into humans. This cutting-edge research involved genomic sequencing, viral isolation, and experiments to see if these viruses could infect humans.

Among those involved in the PREDICT project include Peter Daszak of EcoHealth, Shi Zhengli (aka "Batwoman") from the WIV, and Ben Hu, another WIV researcher, who reportedly fell ill with symptoms resembling those of Covid-19 in November 2019.

Incidentally, Daszak, Shi, and Hu are also linked to Project DEFUSE, a 2018 proposal to create enhanced viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2.

The "RaTG13" Question

One of the most intriguing discoveries linked to the PREDICT project was RaTG13, one of the closest viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and connected to an unexplained pneumonia outbreak at a copper mine in Mojiang, China.

In April 2012, six miners in Mojiang, Yunnan province, contracted severe atypical pneumonia after spending long hours cleaning a bat-infested mineshaft; three would later succumb to the illness.

Dr Li Xu, the doctor who treated six miners, concluded after consulting with Dr Zhong Nanshan that their illness was likely caused by a bat SARS-like coronavirus.

Following this outbreak in 2012, Shi’s team started a long-term surveillance of the mine, taking samples once or twice a year. Within just months of their work, they found RaTG13, a new lineage of SARS-like virus. (Imagine what they could have found with over five years of sampling in Mojiang.)

Initially, USAID took credit for discovering RaTG13. The publicly accessible data repository of PREDICT also showed a bat sampling project in Mojiang in April 2012, the same month and year of the Mojiang outbreak.

But when suspicions about the WIV’s involvement in the Covid-19 origin story began to mount, the agency distanced itself from the virus, claiming in their annual report that it was only discovered through "adjacent work with collaborators."

Recent developments have only deepened the mystery. In 2024, Daszak testified that EcoHealth did not participate in the Mojiang mine expedition, even though initial reports had suggested they were involved. It also appears that sampling data from Mojiang has mysteriously disappeared from the PREDICT data repository.

Yet, a USAID document recently obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request suggests that a researcher working under USAID’s PREDICT project did indeed travel to Mojiang for bat sampling.

So, did USAID play a role in the Mojiang sampling where RaTG13, and perhaps other more closely related viruses to SARS-CoV-2, were found? The next section may shed some light on the agency’s conflicting narrative.

PREDICT: Who Owns the Data?

USAID's PREDICT programme has faced significant criticism over the years. Despite the billions in funding, the agency has failed to predict major zoonotic outbreaks like H1N1 (2009), MERS (2012), Ebola (2013), and Zika (2014).

Many scientists argued that PREDICT was more about public relations than genuine scientific advancement. Some scientists went further, suggesting the programme served as an intelligence-gathering operation.

Internal reviews of the programme also raised troubling questions about who actually controlled the collected data and how transparently it was shared. These concerns were serious enough that in 2018, USAID officials recommended clarifying the agency's legal authority over raw data collected by programme partners.

But here's the catch: the data rights legally belonged to China. PREDICT and its partners could access it, but only as long as China was willing to share.

And even if PREDICT had access, it didn't have legal authority over the collected data, and any findings had to be approved by the host government before release — in this case, the Chinese Communist Party.

In other words, if the WIV had discovered a virus similar to SARS-CoV-2 using PREDICT funding, there was no obligation for them to share those findings with USAID.

China Virome Project: ‘Moving Faster Than Expected’

As the PREDICT project was winding down, the key players behind it were now looking to take things to the next level, and an even bigger initiative, called the Global Virome Project (GVP), was starting to take shape.

The idea was to take virome research to a much larger scale, with even more ambitious goals and greater funding.

This group included Dennis Carroll, head of USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats Division; Jonna Mazet of the University of California at Davis (who, interestingly, had also been director of PREDICT); Peter Daszak from the EcoHealth Alliance; Nathan Wolfe, founder of the DNA database firm Metabiota; and George Gao, head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC).

Eddy Rubin, the Chief Scientific Officer at Metabiota, described the GVP’s potential in a 2017 email: “It has so far been championed by the USAID Pandemic Threat Program, which has already invested about $180 million in a successful pilot project. To take it to the next stage, though, the project needs to become fully global, independent from the US government, with a coordinating non-governmental center or 'hub' linked to national virome projects.”

He also noted that “the project appears to be moving faster than expected with a China component already funded and poised to generate data.”

A cable from the US embassy in Beijing in September 2017 revealed that the Chinese component of the GVP, called the “China Virome Project,” was already funded by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Shi, the leading coronavirus expert at the WIV, was quoted in the cable as saying: “CAS has already allocated funding for GVP-related research.”

In 2018, the GVP was officially launched with a high-profile article in Science magazine by Dr Carroll, Dr Daszak, Dr Mazet, Wolfe, and Dr Gao. The article stated, “Funding has been identified for an initial administrative hub, and fieldwork is planned to begin in China and Thailand in 2018.”

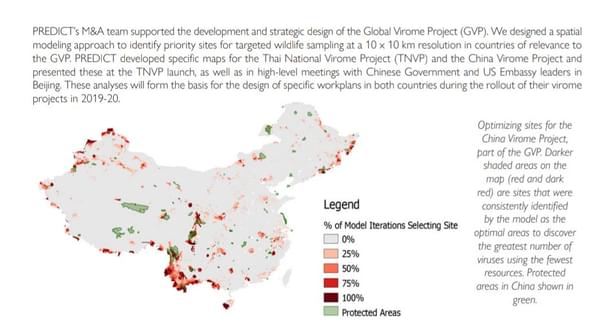

Documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request reveal that in 2018, USAID kicked in nearly $270,969 to help get the project off the ground. USAID’s PREDICT modelling and analysis team had also created “specific maps” for the China Virome Project, which were meant to guide workplans for its rollout in 2019-20.

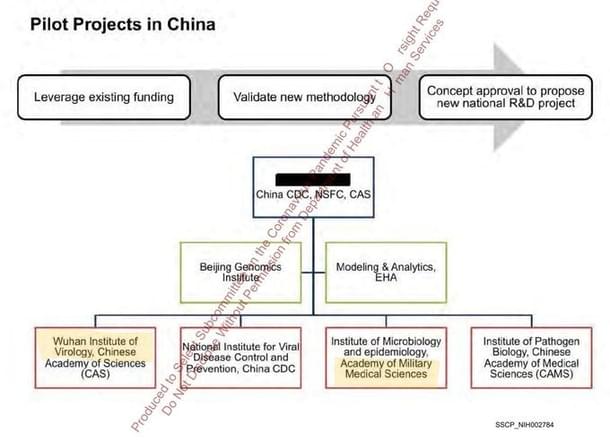

Four Chinese institutions had been entrusted with this project: the WIV, the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, and the Institute of Pathogen Biology. EcoHealth Alliance was responsible for modelling and data analysis.

Despite all this, Rubin privately expressed concerns about data sharing, writing in an email that he didn’t want China to take a leadership role “out of fear of their reluctance to share data.”

A US State Department cable raised the question: “Who will own the samples collected? Where will they be analyzed? Will all GVP data be freely available to the public?”

The issue of data access continued to be a sticking point, especially since the China Virome Project was moving ahead rapidly.

By June 2019, Rubin was privately warning that “China is probably going to do their own thing with regard to what data they collect and how they provide access, no matter what we put together.”

And then, the pandemic happened.

Did USAID Funding Fuel the Pandemic?

In short, USAID’s funding through the PREDICT and GVP programmes helped the WIV collect thousands of bat coronavirus samples and sequences for high-risk experiments, all under minimal biosecurity precautions.

Richard Ebright, a scientist at Rutgers University, described this as a “reckless Indiana Jones-style adventurism.”

Despite pouring millions of dollars into both PREDICT and GVP, USAID struggled to gain access to the very data and sequences it had funded.

While the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has faced intense scrutiny for its role in funding the Wuhan lab, USAID, despite its even larger funding, has been far less transparent. USAID’s PREDICT proposals and reports have yet to be made publicly available.

To fully understand the origins of the pandemic, we must explore the full scope of these programmes.

For now, we are left with an uncomfortable question: in trying to stay ahead of a pandemic, did USAID inadvertently help create one? The answer is still unclear, but one thing is certain — if Covid-19 did indeed originate in a lab, USAID’s funding may have laid the groundwork years in advance.