World

India’s IMF Dilemma: Between An Unfair Past And A Risky Partnership

Deviyani G

May 16, 2025, 07:45 AM | Updated Oct 18, 2025, 10:40 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Amid the heightened focus on India-Pakistan tensions, a significant milestone quietly took place—news came in that India is poised to overtake Japan in 2025 to become the world’s fourth-largest economy, according to the IMF’s April 2025 World Economic Outlook.

The contrast is striking, as Pakistan, facing deep economic challenges, was once again bailed out by the IMF—for the 28th time in the past 35 years.

Dominance of the Global North

The Bretton Wood body has been dominated by the United states ever since its conception in 1944. When the World War II victors decided among themselves that they would be the moral arbiters of the world, many prominent international institutions came to be within their firm hold. Be it the 'permanent 5' of the United Nations Security Council, or the established convention that pertains to the appointment of heads of the World Bank and the IMF, these global institutions happen to be the exclusive ginger clubs of Europe and the States.

The tacit understanding between Europe and the USA has meant that the President of the World Bank is always a U.S. citizen, usually nominated by the President of the United States while the Managing Director of the IMF is always a European, traditionally selected with strong backing from European countries.

So when Pakistan, within whose courtyard resided the notorious Osama Bin Laden, is granted a 1 billion dollar package at the height of tensions with its behemoth neighbour India, the Global North is solely to blame.

India with a mere 2.75 percent voting power, did what it could to prevent the global body’s resources from being used to finance terror. India expressed its strong dissent and abstained from voting for Pakistan's bailout package (voting against is not an option).

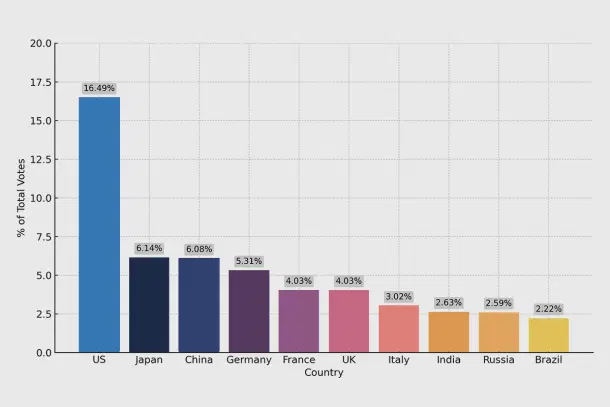

However, with the USA wielding a massive 16.52 per cent of share and China with 6.09 per cent, it was never really in India’s hands.

At the IMF, decisions are taken by consensus, but unlike the United Nations, where each country has one vote, the vote share at the IMF depends on its assigned quota.

Think of the IMF as an exclusive club. To gain entry into it a country will have to pay a subscription fee of sorts. This fee is determined by the size of the quota assigned to it. The formula to calculate the quota considers a member's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), trade openness, economic variability, and international reserves.

Each member also receives a fixed number of basic votes, with the remaining votes proportional to their quota share.

Quotas are denominated in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which are the IMF's unit of account and are valued based on a basket of currencies, including the US dollar, Euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and Chinese renminbi.

The Rise of the Dragon

The IMF aims to conduct a General Review of Quotas at least every five years to assess their adequacy and their distribution to reflect members' relative positions in the global economy. China’s great economic rise was accepted with the internationalisation of the renminbi with its inclusion in the SDR in 2016.

The last increase in IMF quotas was agreed upon in 2010, at a time when emerging markets played a crucial role in the global response to the 2008 financial crisis. To encourage their participation in broader reforms—such as financial market restructuring and a significant expansion of the IMF’s resources—the United States and its G7 partners supported a rebalancing of quotas in favour of these emerging economies.

This increase – which was only formally ratified in 2016 – resulted in a significant transfer of voting power away from the US and Europe to (in particular) China, making it the third largest shareholder in the IMF, just behind Japan. India's share of quotas rose from 2.44 per cent to 2.7 per cent, and pushed India's ranking up from the 11th position to the eighth position.

More recently, the Board of Governors concluded the 16th quota review in December 2023, approving an increase in quotas by 50 per cent. However, the internal distribution of the quotas and thereby vote shares between member countries is yet to be decided. This could potentially be addressed at the 17th General Quota Review which is set to happen in June 2025.

One study by Boston University examined ways to better align the 17th General Quota Review (GQR) with the rising economic significance of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), while also enhancing their voice and representation in IMF governance. The study explored the trade-offs involved in various reform options.

The key findings of the study were:

a) The IMF’s quota formula favours advanced economies due to biased variables. For instance, it uses Market Exchange Rates (MER) instead of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) to calculate GDP, undervaluing emerging economies.

b) It also double-counts cross-border flows under its “openness” variable, skewing results further.

c) While the formula usually applies to new quotas, realigning all quotas strictly by this formula would significantly shift voting power:

-The US would fall to 13.99 per cent, losing its veto—a politically unacceptable outcome.

-China would nearly match the US at 13.84 per cent, reflecting its economic rise but raising political concerns.

-Poorer countries and developing regions outside Asia and Europe would lose voting shares, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, due to slower growth.

India, Caught between the Devil and the Deep Sea

No country's vote share can be increased without its consent. India has long pushed for an expansion of the IMF’s resources and reform of the quota system to fairly represent emerging markets. However, a quota review would certainly mean a large increase in voting rights for China, which is represented far below its economic weight, along with the US losing its veto power.

The Chinese government has had a track record of subverting international institutions. It almost always vetoes in favour of Pakistan at the UNSC and previous attempts at building alternate multilateral institutions like the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have been hijacked by the 'dragon'.

So, it was perhaps in this regard that in 2020, right in the middle of the pandemic, in the throes of the biggest global crisis since the Great Depression, the Indian Finance Minister decided to oppose the IMF’s proposal to issue new SDRs worth $500 billion.

It is to be seen how things are likely to play out post the 17th GRQ. The States for obvious reasons, with an ‘America First’ policy, would want the present distribution to continue.

It had unilaterally thwarted the use of the 15th Review of Quotas to redistribute the voting rights, despite being supported by the majority of IMF member states. Will history repeat itself at the 17th GRQ? With Trump at the helm, things are hard to decipher.

That said, would it still be wise for India to toe the American line? Particularly in light of Trump’s recent claims about using trade as leverage to bring India and Pakistan to the negotiating table during the ‘ceasefire’? His statements warrant caution in any policy regarding the US.

Should India support continuing with the status quo at the IMF, i.e. primacy to the United States, or would it be wiser to accommodate China’s growing influence?

With a 50 per cent increase in the overall quota already approved under the 16th General Review of Quotas (GRQ), is Beijing’s dominance now inevitable? How will the redistribution of voting shares unfold? Could China’s share eventually match that of the United States—and will the Trump administration ever allow that?

As global power dynamics shift, India faces a difficult choice: which superpower should it align with? Strategic decisions loom large for Bharat in the coming years.

As India ascends to become the world’s fourth-largest economy, surpassing traditional powers like Japan and the UK, its voice in global financial governance must reflect this new reality. Yet the path to greater representation is riddled with geopolitical minefields. Aligning with the United States offers familiarity and influence, but risks perpetuating a skewed power structure that denies India its rightful place. On the other hand, empowering China within the IMF could undermine the very multilateralism India seeks to protect, given Beijing’s record of institutional capture and its consistent shielding of Pakistan.

The upcoming 17th General Review of Quotas will be a litmus test—not only of the IMF’s credibility, but also of India’s strategic acumen.