World

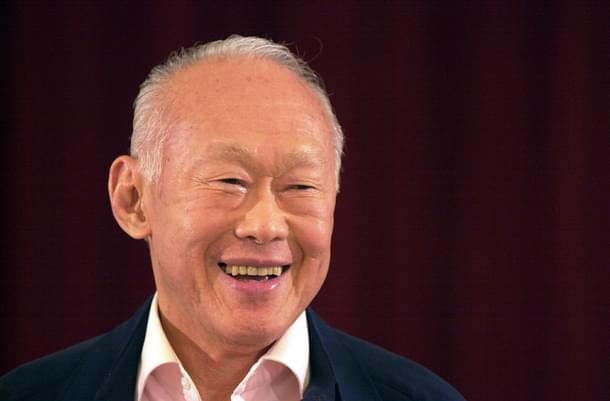

Obit: Lee Kuan Yew - The Gardener Is No More

Poulasta Chakraborty

Mar 24, 2015, 02:04 AM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 08:53 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Today many Singaporeans, old and young, will bid farewell to someone who dedicated his life to the people of Singapore. It is an undeniable fact that Lee was the key driver behind a lot of what we see in present-day Singapore. While many in Singapore as well those around the globe view Lee as the epitome of development and technocracy, others see him as an autocrat, who subjugated his opponents as well as fellow citizens to ensure economic growth.

To these critics, social pluralism and political diversity were expendable in Lee’s quest for growth. They go as far as accusing him of soft-racism for allowing immigration of Chinese workers from neighboring Malaysia to maintain ethnic majority.

But even they accept the fact that Lee scripted one of the most durable stories of economic success in the twentieth-century, stressing on hard work, the rule of law and meritocracy. His alleged cultural biases did not stop him from curtailing institutional racism. Singaporeans were taught to be hospitable, to each other. Almost all the citizens of Singapore can afford the benefits of good public schooling, housing and healthcare.

Born as a British subject in 1923 Lee topped School Certificate examinations in Raffles Institute, earning the then prestigious John Anderson scholarship to attend Raffles College (now National University of Singapore). He also played cricket, tennis and chess as well as debated for the Institution. It is understandable why this overachiever will eventually harbor a deep belief in the concept of meritocracy.

The Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II derailed Lee’s university education. During the occupation, Lee learnt Japanese and eventually found work transcribing Allied wire reports for the Japanese where he listened to Allied radio stations and wrote down what they were reporting in the Japanese propaganda department.

During that time, Lee was asked by a Japanese guard to join a group of segregated Chinese men. Being aware of the brutalities of the Japanese forces, he asked for permission to go back home to collect his clothes first, and the Japanese guard agreed. That ruse saved Lee’s life as the segregated Chinese men were victims of what became known as the Soon Ching massacres.

Seeing how the British had failed to defend Singapore from the Japanese, Lee commented:

It was the catastrophic consequences of the war that changed the mindset, that my generation decided that, ‘No…this doesn’t make sense. We should be able to run this [island] as well as the British did, if not better.

After the war, Lee went on to study at the University of Cambridge, where he read law at Fitzwilliam College. Keeping up with his meritocratic efficiency he graduated with a rare Double First Class Honours. He returned to Singapore in 1949, working with one of Singapore’s earliest law firms. His first experience with politics in Singapore was his role as election agent for his boss John Laycock under the banner of the pro-British Progressive Party in the 1951 legislative council elections.

On 12, November 1954, Lee, together with a group of fellow English-educated middle-class men created the ‘socialist’ People’s Action Party (PAP) with the pro-communist trade unionists. Theirs was an alliance of expedience; the English-speaking socialists needed the Chinese-speaking pro-communists’ mass support base, while the communists needed PAP to cover up their activities since the Malayan Communist Party was illegal by the colonial administration.

In the national elections held on 30 May 1959, the PAP won 43 of the 51 seats in the legislative assembly. Singapore gained self-government with autonomy in all state matters except defence and foreign affairs, and Lee became the first Prime Minister of Singapore on 3 June 1959.

The Singapore-Malaya Federation (1961-1965)

In 1961, Lee began to campaign for a merger with Malaysia to end British colonial rule following Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s proposal for the formation of a federation which would include Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak.

A referendum was held on 1 September 1962, in which 70% of the votes were cast in support of the merger proposal, but that was because the other votes were blank, as Lee had not allowed a “No” option.

As a result, on 16 September 1963, Singapore became part of Malaysia. However, the Malaysian central government, ruled by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), became worried by the inclusion of Singapore’s Chinese majority and the political challenge of the PAP in Malaysia.

There was also simmering tension between the Malays and the Chinese which escalated on July 1964, when a series of riots broke out between the Chinese and the Malays. More riots broke out in September 1964, as rioters looted cars and shops, forcing both Tunku Abdul Rahman and Lee to make public appearances to calm the situation.

Finally, PM Tunku decided to “sever all ties with a State Government that showed no measure of loyalty to its Central Government“.

Lee was adamant and tried to work out a compromise, since he believed that the merger was crucial for Singapore’s survival, but without success. Eventually, Lee had to sign a separation agreement on 7 August 1965, which discussed Singapore’s post-separation relations with Malaysia in order to continue co-operation in areas such as trade and mutual defence. In a televised press conference, he formally announced the separation and the full independence of Singapore:

“Every time we look back on this moment when we signed this agreement which severed Singapore from Malaysia, it will be a moment of anguish. For me it is a moment of anguish because all my life … you see, the whole of my adult life … I have believed in merger and the unity of these two territories….”

Singapore’s lack of natural resources, a water supply that was derived primarily from Malaysia and a very limited defensive capability were the major challenges that Lee and the Singapore government faced.

The Era of Lee (1965-2011)

Following the severance, some of Prime Minister Lee’s main aims were to ensure the endurance of the new state and to retain Singapore’s national identity. Surrounded by more powerful neighbors like China and Indonesia, Lee did not press for the immediate withdrawal of Commonwealth forces from Singapore. Instead, he travelled to England to delay the timing for withdrawal. The cabinet then took steps to build up the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) and requested help from other countries, particularly Israel, for training and facilities. Lee also introduced conscription whereby all able bodied male Singaporean citizens age 18 and above are required to serve Singapore’s armed forces.

Recognising that Singapore needed a strong economy in order to survive as an independent country, Lee launched a program to industrialize Singapore and transform it into a major exporter of finished goods. He encouraged foreign investment and secured agreements between labour unions and business management that ensured both labour peace and a rising standard of living for workers. But initially the cabinet had to pressurise the nation’s labour movement to accept the provisions locked under the Employment and Industrial Relations Acts of 1968 specifically the ones that outlawed strikes.

To ensure honesty among Government officers PM Lee introduced legislations which gave the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) greater power to conduct arrests, call up witnesses, and investigate bank accounts and income-tax returns of suspected persons and their families. Believing that ministers would maintain a clean government if paid well, he proposed to link the salaries of ministers, judges, and top civil servants to the salaries of top professionals in the private sector. He also believed that financial success will attract more talent for the public sector.

Although Singapore surged through the economic scene by having less bureaucratic tangles and flexible trade laws, many in the opposition socialist party complained about Lee fostering inequality between industrialists and laborers. But Lee went on with his reforms and by the 1980s Singapore had a per capita income second in East Asia only to Japan’s, and made the country a chief financial centre of Southeast Asia.

But there was a catch; “Freedom of the press, freedom of the news media, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore,” is a quote attributed to Lee and he followed it to the hilt regarding issues of dissent and civil liberties. His response to opposition whether from the socialist party members or trade-unionists was simple: hefty lawsuits and imprisonment.

Lee Kuan Yew had no qualms even in interfering in private lives-

Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn’t be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters – who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think.

This streak of putting down dissidence began in the early 1960’s when as a debutant PM Lee launched Operation Coldstore arresting a total of 117 members of the Malaysian Communist Party under the Internal Security Act.

Lee took his belief in meritocratic efficiency a bit too far in the mid-1980s when he incentivised non-graduates to sterilise themselves and graduates to procreate, but the policies were short-lived because Singaporeans were not in agreement with it.

In 1990 Lee’s successor as prime minister, kept him in the cabinet as the senior minister, from which Lee exercised significant political influence. In 2001, Lee was elevated as the “minister mentor,” a position he held until 2011, when he finally stepped down from the cabinet. He continued to hold his seat in Parliament, however, winning reelections from 1991 till 2011.

With his passing away we see an end to a glorious chapter in Singapore’s history. His legacy is his dedication to develop Singapore as understood from this statement he made in the National Day rally in 1988-

Even from my sick bed, even if you are going to lower me into the grave and I feel something is going wrong, I will get up.