World

Seven Takeaways From Putin's India Visit

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Dec 08, 2021, 12:37 PM | Updated 12:55 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

There was a fair bit of buzz before President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, landed in Delhi on 6 December for his annual summit with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

One group, focusing solely on optics, said that if the visit was less than a day this time too, as it had been on the previous two occasions, then it signalled a perfunctory event of peripheral consequence. As it turned out, the duration of Putin’s sojourn in India was far less than the sceptics’ wildest predictions; he stayed for less than five hours.

Another said, with Bismarckian gravitas, that Putin was arriving to seek Modi’s approval to wage war on Ukraine, and pointed to the timing – the meeting in Delhi was taking place less than a day before a Russia-America summit. This is pure humbug, because Putin needs as much approval from Modi to deal with Ukraine, as Modi does from him to conduct surgical strikes into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

A third said that Putin was in Delhi to balance ties between India and China. That’s probably true in a philosophical sense, because Russia does seek a tranquil Eurasian space, with which to balance the West. But, to presume that this goal is a simple process, which might be successfully concluded in a brief bilateral visit, is to betray one’s understanding of geopolitics – or lack of thereon.

A fourth voice, a prominent American expert on China (and a favourite among our usual suspects), authoritatively declared that more arms sales, by Russia to India, would only further confirm that Russia was now a ‘de-facto member of the anti-PRC coalition regardless of Putin/Xi Jinping made-for-TV amity displays’. What did that make Russia then – an American ally?

And yet, in spite of the buzz sought to be created by such absurd musings, it was an important meeting.

The optics first: after seven years of multiple, periodic interactions, Modi and Putin met on the lawns of Hyderabad House as two men who know and respect one other. The photo-op was consequently brief, and both leaders gamely read out their opening remarks before rushing off for a lengthy discussion behind tightly-closed doors. Modi called Putin his ‘dear friend’, and Putin called India a ‘great power’.

Meanwhile, more bonhomie was on display during the 2+2 meetings – between the Foreign and Defence ministers of India and Russia – which is where the nuts and bolts work gets done.

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh exchanged gifts with his Russian counterpart, General Sergey Shoigu, while our Minister of External Affairs Dr S Jaishankar and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov elbow-bumped and chatted amiably while posing for the press, before withdrawing to extensively discuss the global situation.

The meat of the matter was outlined by Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla, after Putin departed, and was detailed in a surprisingly long joint statement which ran to 99 paragraphs. Six inter-governmental agreements, five of which covered cultural, scientific and administrative matters, were also signed. The most significant one was a ten-year agreement to continue extant defence programs, while also planning to add new ones.

This was underscored separately by Minister Lavrov, who stressed on ‘the India-Russia Special and Privileged Strategic Partnership’ – which is an old code for confirmation that the two countries will continue to collaborate actively in key sectors like energy, security and defence.

What does this mean in material terms?

First, India has decided to source more crude oil from Russia at attractive, undisclosed discounts (the phrase used is ‘preferential pricing’). This is a policy shift which, when analysed in conjunction with the prospects of India also increasing crude purchases from America, means at least two things.

One, that India is working towards insulating itself from the painful vagaries of price shocks; and, two, that both America and OPEC would now be forced to offer India equally competitive rates. The customer is always right.

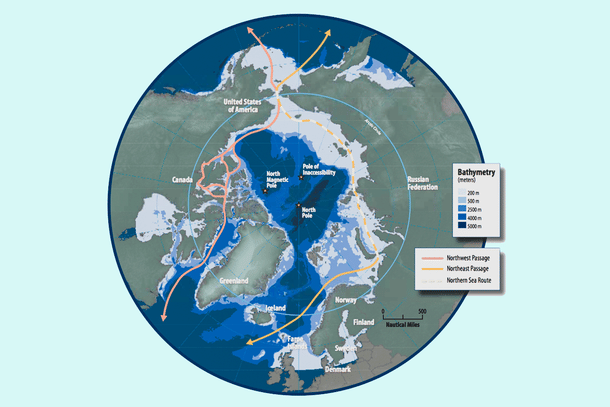

Second, and rather interestingly, the joint statement says that both countries will explore the ‘Northern Sea Route’ to increase both crude and LNG supplies from Russia. This is a formal Russian term for a shipping route running within their economic zone, along their Arctic coast. The reference allows for multiple interpretations.

Hydrocarbons dispatched to India from Siberia, for example, could travel east along the Arctic rim, through the Bearing Straits, down into the Philippine Sea, and then west to India along the equator. If so, our crude supply would circumvent the Suez Canal, the Gulf of Oman, and all its attendant, perennial, geopolitical uncertainties.

Equally, the crude could be shipped west, around Europe, and through the standard Suez route, thereby reducing the risk of any potential impediments being imposed by China in times of tension. Either way, it means that India is looking to expand and further secure its supply options.

In addition, this option lets Russia (and India, laterally) avoid American sanctions, since crude oil (or LNG) loaded and dispatched from a Russian port directly to a port in India, and paid for in a currency other than the US Dollar, would automatically fall outside such sanction nets. The Russians have actually been working on a similar strategy with China, wherein, crude loaded from Baltic ports would use the Northern Sea Route, and payment would be in Yuan, so there is precedence.

Third, the two countries have decided to increase trade along the International North-South Transport Corridor (INST), which runs over sea and land from India, through Iran, the Caucuses (specifically through Armenia and Georgia; not Azerbaijan), into Russia. Pertinently, Chabahar Port in Iran was mentioned in the joint statement.

This is a finger in the eye for China’s ambitious Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI), since the INST is not only the shortest and cheapest trade route into Europe, but it also avoids Afghanistan, Central Asia, the troubled Middle East, and multiple maritime bottlenecks.

It is equally a message to America that their persistent isolation of Iran cannot last forever. Swarajya hinted at this while covering last month’s Delhi conference of regional security on Afghanistan, which was attended by Russia, the Central Asian countries, and Iran; and again, in the build-up to Putin’s arrival in Delhi.

Of course, this decision has serious geopolitical consequences and will be contested, but this is the meaning of multipolarity – that other nations have their own aims, which cannot be held perennially hostage to the intractable interests of one.

At some point in time, the West will have to accept that one of two short, cost-effective, secure trade routes linking Europe and Asia over land need to be resurrected – either straight north from the Makaran Coast through what is now Pakistan, or northwest along the Zagros, the Caucuses, and the steppes of Russia. This is how it was throughout history, and this is how it must be again.

Fourth, a logistics pact, like the one India shares with America, did not materialise. The thinking was probably driven by strong pressure from America against it, and the usual suspects may give this some spin.

But objectively read, a military or strategic grouping which covers the Indian Ocean threatens China far more than it does Russia. Besides, both India and Russia already share berthing rights at Cam Ranh port in Vietnam, and the Russians have the Eastern Mediterranean inlet covered by their Tartus naval base on the Syrian coast, so there is no desperation in Moscow on this point.

Fifth, the Russians are expected to expand their investments in India, from petroleum to petrochemicals. Nayara Energy, which is a joint venture between Indian and Russian firms, bought out Essar’s Vadinar refinery some years ago. This company will probably be the vehicle for the proposed expansion of investments, since it was referred to by name in the joint statement.

Sixth, India and Russia intend to replicate the Rooppur model to jointly build nuclear power plants in other countries. This is a reference to a plant of Russian design which is being built at Rooppur, Bangladesh, by Indian, Russian and Bangladeshi companies.

Concurrently, it has also been agreed now that plans for a second major nuclear power station complex, similar to the massive one set up by the Russians at Kudankulam, will be finalised soon. We may therefore expect a fresh round of wearisome protests from the usual quarters as soon as the second site is decided upon.

Seventh, and of immediate consequence to India, both nations stated for the record that their interests in Afghanistan, and their views on the situation there, are the same. In one sense, this formal revelation of what had always been suspected, is not surprising, since the Amu Darya is to Russia, what the Khyber Pass is to our subcontinent – rim lines which are allowed to get out of hand only at common peril.

This is important, because it means that both concur on the root cause of the problem, and the potential for that root cause to fly out of control. It also means that any action India takes in this regard would not conflict with Moscow.

Boiled down, the verbiage reflected a telling phrase from PM Modi’s opening remarks: “India and Russia have identical views on all the regional and global issues”.

There was a lot more, like the rifle factory at Amethi to build AK-203s, cooperation in space, and pharmaceutical sales to Russia, but the above seven points were the more important ones because of their manifest geopolitical implications.

Thus, in conclusion, we see that the Indo-Russian summit was anything but the staid or inconsequential affair some made it out to be. So, rather than swing between extremes, to either rhapsodise or castigate it, a more accurate interpretation of the Modi-Putin meeting is that it was a hard-nosed affair, which jointly seeks to serve the interests of both nations, while accommodating the vicissitudes of an unruly world.

Also Read: Russia-India-China Foreign Ministers' Meet: What Gives?

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.