Bihar

Warning By Example: Why Bihar's Policing Crisis Is A Cautionary Tale For Other States

Abhishek Kumar

Jul 14, 2025, 06:10 PM | Updated 06:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

As one crosses into Bihar along the Gorakhpur–Gopalganj route, the Bihar Police are quick to flag down vehicles at makeshift barricades, supposedly to check for illegal alcohol smuggling, often doing so with arbitrarily.

It frustrates drivers, but that's the way things are.

Locals, however, see it as a futile exercise, pointing out that smugglers typically use the farms flanking the roads and lighter vehicles to move undetected.

This leakage captures the Bihar Police’s current predicament. Its focus remains fixated on alcohol, once called jugular vein of crime, while the very crimes once blamed on alcoholism are now increasingly seen as consequences of the prohibition itself.

Gopal Khemka Murder Case

On 4 July 2024, Bihar’s capital Patna was shaken by the brutal murder of Gopal Khemka, a prominent businessman and former BJP leader with deep political connections.

According to the police, Khemka was murdered by a shooter named Umesh Yadav. Yadav had been waiting for him outside his residence at Kataruka Niwas, situated between Hotel Panache and Hotel Maurya in the high-profile Gandhi Maidan area. As Khemka sat in his vehicle, honking to enter his house, Yadav fired a single shot, killing him on the spot.

It was only after the incident gained traction on social media and other platforms that the police sprang into action, arresting Yadav along with Ashok Sao, Khemka’s business rival and the alleged mastermind behind the murder.

However, this swift response is being viewed in isolation, largely due to the high-profile nature of the case.

In contrast, other violent crimes, such as the mob burning of five family members in Purnia or the murder of three individuals in Siwan over illegal tax collection, have drawn far less attention, with victims and their families still waiting for any meaningful pursuit of justice.

Meanwhile, incidents of loot, theft, extortion, and other forms of organised crime are on the rise across the state. It may sound harsh, but Bihar now appears just one step away from slipping back into its infamous Jungle Raj era.

All it would take is one high-profile kidnapping, and the perception of law and order in the state could collapse entirely. In such a scenario, Nitish Kumar risks being likened to Joe Biden, under whose watch the United States abruptly handed Afghanistan back to the Taliban after over two decades of conflict.

To many, these incidents are routine preludes to the upcoming assembly elections, scheduled for later this year. The dominant political narrative, predictably, revolves around both sides trading blame, reducing serious crimes to mere talking points in a partisan slugfest.

But for a small, politically aware minority tracking crime trends and the network of criminals, the issue runs much deeper. It is a structural problem that demands a nuanced understanding of how crime in Bihar has evolved and how political choices have shaped that trajectory.

On its journey of redemption after the Jungle Raj, Bihar’s political establishment made several critical missteps, the consequences of which are now playing out in full view.

Shadows from Jungle Raj and Beyond

Bihar’s law enforcement machinery has remained in tatters since the late 1960s. Caste- and religion-based violence, gang wars, and organised crime surged in the wake of a large section of the state’s meritorious youth being absorbed into national-level agitations, ranging from the Emergency to the JP movement, the pro-Mandal mobilisation, and more.

The slow build-up through the 1970s and 1980s reached its peak in the 1990s, when the criminal underworld morphed into a battlefield of caste wars. Criminals found protection along caste lines. The anti-upper-caste narrative, once a tool of social empowerment, was now co-opted to extend political sympathy and cover to criminal elements from lower castes. This was the same principle on which Naxalism also found traction in Bihar.

Instead of eliminating criminal networks, the political establishment indirectly fuelled them. The institutional bias became evident when then Chief Minister Rabri Devi was urged to visit the site of a massacre. She reportedly declined, saying the victims were not her voters, clearly implying there was no political utility in the visit.

Amidst all this, the condition of Bihar’s police force deteriorated. Recruitment stalled, training infrastructure collapsed, basic amenities like food and lodging were neglected, and overall morale hit rock bottom. By the time Nitish Kumar assumed office in 2005, Bihar had just around 51,000 police personnel to protect the fundamental right to life of over 9.3 crore people.

This translated to a police-to-population ratio of just 54.5 per lakh, far below the national average of 145 and the United Nations’ recommended benchmark of 222 police personnel per lakh.

For context, in 2023, a far more stable period than 2005, India’s national average stood at 152.8. In 2005, each police personnel in Bihar was effectively responsible for the safety of approximately 1,833 individuals, more than double the national average of 831 in 2025.

For Nitish Kumar, the challenge was twofold: improving this abysmal ratio while simultaneously confronting entrenched criminal elements. Senior police officers demanded a free hand, a request the new government granted. In just three and a half years, Bihar’s law and order machinery oversaw the conviction of over 70,000 criminals, a number that exceeded the strength of the state’s police force itself.

Simultaneously, the Kumar administration initiated an aggressive recruitment drive.

Beyond restoring law and order, boosting police recruitment served two of Kumar’s flagship promises: employment generation and social justice. The prestige of a uniform, combined with Kumar’s image as a master social engineer, gave rise to a new model of recruitment.

Kumar also became the first socialist leader to fully implement the recommendations of the Mungeri Lal Commission, sanctioned by Karpoori Thakur in the 1970s, which had advocated for the recognition of the Extremely Backward Classes (EBC). While Lalu Prasad Yadav implemented the Mandal Commission’s recommendations for the OBCs, the EBCs remained unaddressed.

Kumar brought them into the mainstream by bifurcating the OBC category into OBCs and EBCs. According to the latest Bihar Caste Survey, these groups now comprise 27 per cent and 36 per cent of the state’s population, respectively.

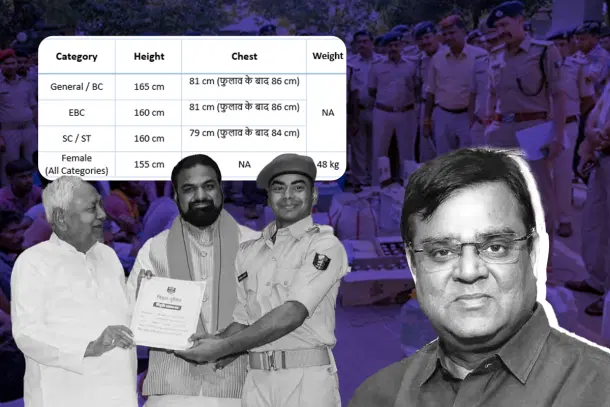

A Comparative Look At Physical Criteria and Reservations In Police Recruitment

In government jobs, including recruitment in police forces, 18 per cent of seats in Bihar are reserved for the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs). EBC candidates also benefit from relaxations in physical parameters.

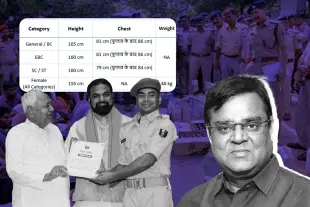

For instance, the minimum height requirement for male candidates from General and OBC categories is 165 cm, whereas for EBCs, Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Scheduled Tribes (STs), it is relaxed to 160 cm. This amounts to a reduction of 5 cm, or approximately 3.03 per cent below the standard benchmark of 165 cm.

While this relaxation is well-intentioned to promote inclusion, it has created a perception deficit among sections of the population.

A comparison with other states is instructive.

In Haryana, the minimum height requirement for male candidates from the General category is 170 cm. For candidates from all reserved categories, it is slightly relaxed to 168 cm, a difference of 2 cm, or roughly 1.18 per cent less than the benchmark.

The Delhi Police allows a reduction from 170 cm to 165 cm for males belonging to certain reserved categories, mostly SCs, STs, and candidates from hilly regions. Though the gap is 5 cm, it represents only a 2.94 per cent reduction from the standard. Importantly, these relaxations are granted mostly to communities with documented issues related to average height.

Uttar Pradesh takes a somewhat different approach. The height requirement for OBC and SC males remains the same as for the General category, but for STs, it is reduced from 168 cm to 160 cm, a steep 4.76 per cent drop. However, this is widely seen as acceptable since most tribal communities are known more for agility than for height or physical bulk.

Bihar stands apart in that it applies the same 5 cm relaxation across EBCs, SCs, and STs. This approach is seen as unscientific, especially considering that the Bihar government itself recognises differences among these groups in other criteria. For instance, chest measurements for EBCs are set at 81 cm (without expansion) and 86 cm (with expansion), whereas for SCs and STs, the measurements are 79 cm and 84 cm respectively.

By contrast, Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh restrict physical relaxations to communities with more structurally uniform and well-documented disadvantages, such as STs and residents of hilly or remote regions. These states also maintain more consistent chest measurement relaxations.

Another significant point is that Bihar’s 5 cm reduction begins from a lower base of 165 cm, not 170 cm as in Delhi and Haryana, or 168 cm as in Uttar Pradesh. As a result, Bihar ends up with a relatively larger proportional difference between standard and relaxed requirements. This, in turn, creates a more pronounced competency gap by including a broader range of communities under relaxed norms.

To mitigate this, Bihar introduced a uniform physical endurance test, requiring candidates to run 1.6 km (approximately one mile) in under six minutes. A graded system also awards higher marks to those completing the run in less time. Only Delhi matches Bihar’s standard in terms of speed.

However, while both Bihar and Delhi test speed, they appear to compromise on endurance. In Haryana, male candidates must run 2.5 km in under 12 minutes, and in Uttar Pradesh, the benchmark is 4.8 km in 25 minutes.

After addressing EBC representation, the Nitish Kumar government turned its focus to increasing the number of women in the police force. In 2013, the state introduced a transformative policy, reserving 35 per cent of seats for women in the constabulary and Deputy Superintendent of Police ranks. This initiative came in the wake of several pro-women education schemes introduced by the government starting in 2006.

At the same time, the government announced 43,000 new police vacancies in a five-year window, aiming to increase the police-to-population ratio to 69 per lakh. The announcement acted as a powerful motivator, especially for women, and the recruitment drive yielded remarkable results.

At present, women make up more than 28.5 per cent of the Bihar police force, with the total number nearing 36,000. In the latest round of recruitment, 21,391 joining letters were issued, out of which 11,178, or a striking 52 per cent, were handed to women who qualified under relaxed norms.

However, the recruitment process is marred by excessive uniformity and a lack of recognition of intersectionality.

For example, regardless of their social category, all female candidates must meet the same minimum height requirement of 155 cm. This implies either that the state government assumes women across all categories to be equally disadvantaged in terms of nutrition and social conditions, or that it has deliberately set the bar lower to achieve inclusion targets at the cost of physical standards.

The answer is difficult to ascertain. In fact, this writer’s interactions with former trainers elicited surprise that such a question would even be raised.

If the first explanation is true, then Bihar is a unique case. Other states set different physical benchmarks for different social categories of women.

Uttar Pradesh offers a more differentiated approach, requiring a minimum height of 152 cm for General, OBC, and SC women, and 147 cm for ST women. These criteria reflect genetic, nutritional, and regional disparities among communities. Similarly, Delhi allows women from hill and tribal regions to qualify at 155 cm, while other women must be at least 157 cm tall.

In Haryana, the general requirement is 158 cm for General category women and 156 cm for those from reserved categories.

Looking at the deviation from the male General category height requirement in each state offers another angle for comparison.

In Bihar, the difference between the male (165 cm) and female (155 cm) minimum height is 10 cm, which amounts to just 6.06 per cent. The state applies this flat standard to all women, regardless of background.

In contrast, Delhi’s male benchmark is 170 cm, while female candidates must be at least 157 cm tall, with relaxations to 155 cm for women from tribal or hill areas and to 152 cm for daughters of Delhi Police personnel. This produces a difference ranging from 13 cm to 18 cm, or 7.65 to 10.59 per cent.

Haryana’s standards yield a height gap of 12 to 14 cm, or 7.06 to 8.24 per cent, between General category men and women.

Uttar Pradesh has the widest variation. With a male benchmark of 168 cm, women from General, OBC, and SC categories must be at least 152 cm tall, and ST women just 147 cm. The difference spans 16 to 21 cm, or 9.52 to 12.5 per cent.

Despite the numerical advantages Bihar offers in terms of relaxed criteria, they are nearly nullified in absolute terms. Bihar enforces higher height and fitness requirements for women than most of its North Indian counterparts. Compared to all major North Indian states, Bihar only outperforms Uttar Pradesh in terms of minimum height required for female constables. Delhi and Haryana select taller candidates on average.

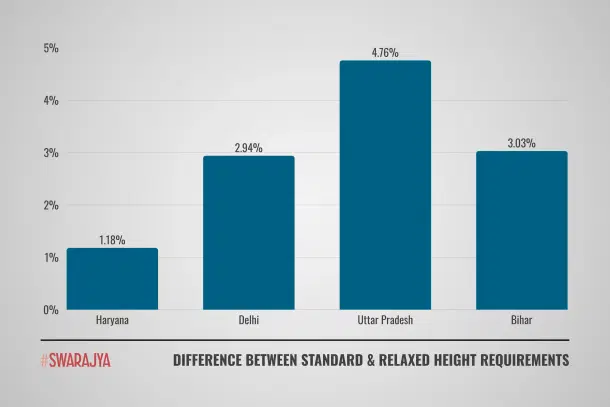

This issue is compounded by the state’s affirmative action policies, which result in a high proportion of candidates qualifying under relaxed norms. In Bihar Police, EBCs (18 per cent), SCs (16 per cent), and STs (1 per cent) collectively constitute 35 per cent of reserved seats. Of these, women occupy 35 per cent under horizontal reservation, with the remaining 65 per cent filled by men.

That means 22.75 per cent of all recruits are men admitted under relaxed physical standards (65 per cent of 35 per cent). Adding the 35 per cent horizontal reservation for women, at least 57.75 per cent of all selected candidates are assessed using relaxed physical benchmarks, leaving only 42.25 per cent competing under the stricter General category standards.

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh runs one of the most stringent police recruitment processes. Although it too follows a reservation policy, only STs with a 2 per cent quota enjoy relaxed physical standards. Accounting for 20 per cent horizontal reservation for ST women, the share of male ST candidates qualifying under relaxed norms is just 1.6 per cent of total seats.

With women of all categories occupying 20 per cent through horizontal reservation, only 21.6 per cent of candidates benefit from relaxed norms, leaving a robust 78.4 per cent to clear stricter benchmarks.

In Haryana, the total reservation pool includes SC (20 per cent), BC-A (16 per cent), BC-B (11 per cent), and EWS (10 per cent), adding up to 57 per cent of candidates qualifying under reserved categories. However, Haryana’s relaxed criteria are more uniform and do not result in large physical disparities between groups.

In Delhi Police, 33 per cent of seats are reserved for women and 7.5 per cent for STs. Including 33 per cent horizontal reservation for ST women, about 5 per cent of total male candidates qualify under relaxed norms.

When including relaxations for certain regional and ethnic groups like Garhwalis, Gorkhas, Marathas, and residents of the Northeast and other hilly areas, the estimated total under relaxed norms remains below 40 per cent. This means more than 60 per cent of candidates in Delhi Police are assessed under stricter standards.

Why Does It Matter?

In recent years, there have been increasing demands to sensitise the police force and to reduce its reliance on coercive methods. When viewed from the lens of public safety and community trust, this argument holds weight.

Police personnel, particularly those at the constabulary level and a few ranks above, who form the immediate and most visible face of law enforcement, are expected to be as informed, educated, and empathetic as possible towards the local population.

This may partly explain why a reduction in physical standards does not provoke immediate public outcry.

However, it is important to consider the broader context behind such relaxations in standards or the push for less forceful policing. These shifts often emerge during relatively peaceful times. For instance, Bihar found it appropriate to ease entry standards for police recruitment when its law and order machinery was actively prosecuting criminals and the state enjoyed a semblance of stability.

In the United States, Democrat-governed states led the charge on radical measures such as "defunding the police" during the George Floyd protests.

The common reasoning behind such efforts is that people fear the police primarily because of their state-backed power to use force, not necessarily due to their individual physical prowess.

While this may be true in well-developed or affluent regions, it does not hold up in grossly underdeveloped states like Bihar and Jharkhand, where police encounter two distinctly different types of criminals.

"On one hand, you have petty criminals who commit theft out of desperation, often coming from backgrounds where even basic facilities are lacking. On the other hand, there are members of organised gangs controlling hundreds of crores of rupees.

The demeanour of both can appear the same. At first glance, it is difficult to know who can be dealt with softly and who might suddenly unleash a hail of bullets," said an officer currently serving in Jharkhand.

He added that benevolence is usually respected only when it comes from a position of perceived strength. "When we interact with someone, they don’t see it as the state dealing with them. For them, it is just them and a powerful person. If I do not appear stronger than them, my sympathy will not be returned with respect."

This is a reality even the average person can intuitively understand.

Ultimately, the battle for perception becomes crucial—not just for catching criminals, but for preventing crimes in the first place. Fear of consequences is just as effective a deterrent as any sense of civic duty or affection toward fellow citizens.

Having a sympathetic, inclusive, and representative police force is the need of the hour. But this goal can be achieved without significantly lowering entry standards. Instead, the focus should be on better training to develop a capable and discerning force, one that knows how to read a situation and act accordingly. Inclusivity does not have to come at the cost of competence or strength.

Bihar experienced the downside of such compromises when it initially based merit lists primarily on written examinations. In 2017, it shifted course and made physical tests a criterion for merit.

However, the core issues persist. The state continues to set a low baseline for competition and then grants a concession of at least 3 per cent in physical standards to nearly 58 per cent of the population in the name of inclusivity.

Misplaced priority put Police Department under pressure

Despite the state’s low police-to-population ratio, Nitish Kumar enforced alcohol prohibition in Bihar, fully aware of the pressure it would place on already stretched law enforcement resources. Yet Kumar had both social and political justifications for the move.

Multiple surveys, including the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), had shown alarming levels of spousal violence, with alcohol cited as a major contributor. Socially, the prohibition was aimed at curbing domestic violence. Politically, it was seen as a means to secure the loyalty of women voters for at least two election cycles.

Post-ban surveys recorded increases in household spending on food and clothing and reductions in violence. A Lancet study even claimed that the ban saved at least 2.1 million women from domestic abuse.

However, for Bihar’s law enforcement agencies, the consequences were drastically different. Overnight, they were seen not as agents ensuring public safety but as enforcers of a state-imposed moral code. Police and Excise officials were given little time to prepare for the operational burden that the law imposed. The government, meanwhile, enacted a sweeping and severe legal framework to enforce prohibition.

The state machinery responded with intensity. In the first 22 months after the ban, authorities conducted 6,13,194 raids, filed 97,074 complaints, and arrested 1,15,243 individuals. Between October 2016 and February 2018 alone, 1,02,879 people were arrested.

Breaking this down further, Bihar Police, operating across 38 districts, averaged 935 raids and 175 arrests per day.

Over time, police became more active in enforcing the prohibition than the Excise department. In the first 12 months of the ban, police accounted for 55 per cent of the arrests, but this jumped to 68 per cent in the following 10 months. Conversely, the Excise department’s share dropped from 45 per cent to 33 per cent.

When it came to cases registered, the police were responsible for 57 per cent, while the Excise department registered 43 per cent. According to the state’s Prohibition, Excise and Registration Department Secretary Vinod Uniyal, as of 31 August 2024, a total of 8.43 lakh cases had been registered. Of these, the Excise department registered 3.70 lakh cases.

Interestingly, the ratio between the departments remained the same as in 2018. Whether this reflects remarkable consistency or unbelievable coordination is open to interpretation.

From 1 April 2016 to 31 August 2024, 2.79 lakh individuals were arrested for violating prohibition laws, an average of 93 arrests per day. Though the figure may suggest improvement, ground-level officials report a different picture. In numerous instances, Bihar Police have been caught planting liquor in vehicles to extort bribes.

In one such case involving alleged misuse of power under the liquor law, Patna High Court Judge Justice Purnendu Singh made scathing observations against the police, Excise, State Tax, and Transport departments.

"The draconian provisions have become handy for the police, who are in tandem with the smugglers. Innovative ideas to hoodwink law-enforcing agencies have evolved to carry and deliver the contraband. Not only police officials, excise officials, but also officers of the State Tax department and the transport department love the liquor ban; for them it means big money," the Court observed.

Justice Singh also highlighted that enforcement disproportionately targets consumers, who are often poor daily wage earners and the sole breadwinners of their families. These individuals are routinely arrested, while syndicate operators and kingpins are largely ignored.

Data backs this claim. Of the 2,12,323 arrests made by Bihar Police between April 2016 and January 2020, only 19,500 were suppliers.

The prevalence of poverty among those affected is one issue on which both Prashant Kishor and Tejashwi Yadav agree. Yadav estimates that Dalits and other backward communities account for 99 per cent of the total arrests.

“So far, over 3.86 crore litres of liquor have been seized, out of which over 2.1 crore litres is foreign liquor and over 1 crore litres is country liquor. It proves that the consumption of foreign liquor is high in Bihar. It is not the poor and deprived classes who will drink more than 2.1 crore litres of foreign liquor,” Yadav said at a press conference in April.

The scale of operations under prohibition is massive. The Prohibition Control and Command Centre in Patna monitors highway and border checkpoints round the clock through live camera feeds. The state has deployed 41 drones and operates 84 permanent checkpoints. Additionally, it uses 33 sniffer dogs, 890 breath analysers, and 12 handheld scanners to detect contraband.

Even by conservative estimates based on arrests, cases, and operational footprint, at least 20 per cent of the state's police force is dedicated to alcohol prohibition. The daily number of tip-offs has increased fourfold from 75 just a few years ago to 300 today.

One might assume that this surge in tip-offs signals improved vigilance and growing fear among smugglers. The numbers, however, tell a different story. The scale of the problem has only intensified.

In 2023, Bihar Police registered 72,062 prohibition-related cases, arrested 1.43 lakh people, and seized 17,183 vehicles. The average daily seizure rate was 10,858 litres, totalling 39.63 lakh litres, around 10.25 per cent of all liquor seized till 31 March 2025.

The figures for the seven-month period from August 2024 to March 2025 are even more alarming. During this time, the state registered over 93,000 new cases and made 1.53 lakh arrests, which is 10,000 more than in the entire previous year, despite covering five fewer months.

According to the most recent official data, of nearly 9.37 lakh registered cases, only 44.7 per cent (4.19 lakh) have been disposed of. This has led to the sentencing of 4.16 lakh accused. Meanwhile, legal proceedings are pending regarding the seizure of over 8,200 buildings or plots and 1.4 lakh vehicles.

In 2021, former Chief Justice of India N. V. Ramana had called the Bihar liquor law an example of legislative overreach and lack of foresight.

"There are three lakh cases pending in the courts. People are waiting for justice for a long time and now the excessive cases related to liquor violations put an additional burden on courts," he said.

He further noted that bail applications under the liquor prohibition law had inundated the High Court. "Due to short-sighted policies implemented by different governments, it is affecting the work of courts in the country. Every law needs to be discussed thoroughly and with solid points before implementation," he added.

Prohibition as a Source of More Evil

A vast body of criminological literature now links alcohol prohibition to a rise in violent crimes. It is also a matter of common sense: when alcohol is legal, disputes arising from its purchase or sale are more likely to be settled by legal means, unlike disputes in the shadowy realm of illegal liquor.

Bihar is no exception.

In the initial months of strict enforcement, the emergence of a parallel black market pushed alcohol prices beyond the reach of the poor and many young addicts. Unsurprisingly, this created a vacuum that was quickly filled by other intoxicants.

More than one-fifth of those priced out of the black market shifted to alternatives such as ganja (marijuana), toddy, cough syrup, inhalants, hashish, and more.

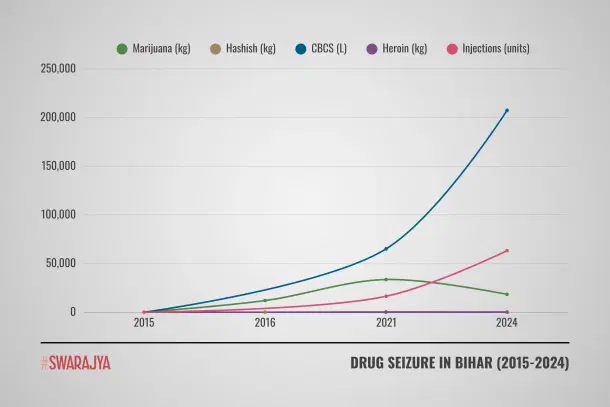

While the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) seized only 14 kg of marijuana in Bihar in 2015, the figure rose to 10,800 kg in 2016 and surged to 33,603 kg by 2021. Although marijuana seizures have declined in recent years, the 2024 total still stood at a troubling 18,356 kg.

Similarly, hashish seizures increased from 0 kg in 2015 to 395 kg in 2021, before dipping to 195 kg in 2024. Heroin seizures followed a similar trajectory, with 0.5 kg in 2015, 9.62 kg in 2021, and 53.35 kg in 2024.

CBCS (Cocaine-Based Cough Syrup) volumes tell an even starker story. In 2015, no seizures were recorded, but by 2021, 65,079 litres were confiscated, rising dramatically to 2,07,405 litres in 2024.

These patterns are consistent across categories such as opium, poppy husk, morphine, tablets, and injectable narcotics. Local media frequently circulate videos of children and teenagers lying unconscious in public spaces after taking injections. Concerns around injectable drugs have risen sharply in recent years.

Although the NCB did not record injection seizures in 2015, the data for 2021 and 2024 reveal 16,392 and 63,208 units respectively.

The pursuit of cheap dopamine hits has diminished the value of human life in Bihar post-prohibition. While increases in household spending on milk and saris are often cited to showcase the policy’s success, this optimism is sharply contradicted by an emerging trend: the reorganisation and rearming of Bihar’s underworld. Initially manifesting through passion crimes, it has since taken on a more structural and organised form.

A study titled Economic Analysis of Liquor Prohibition in Bihar on the Efficiency Criteria by Dr Shivani Mohan and Dr Manoranjan Kumar highlighted how crime rates rose following prohibition and how it overwhelmed the legal machinery.

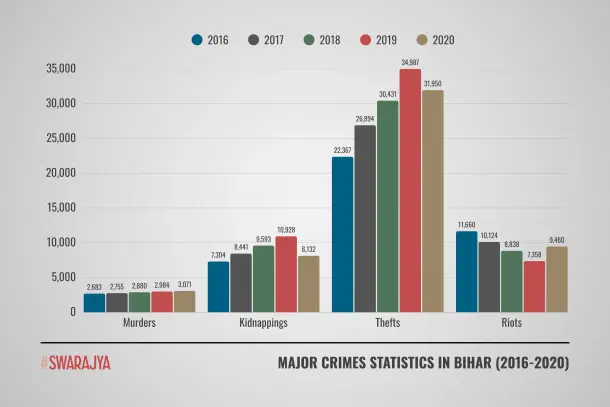

Between 2016 and 2020:

Murders increased from 2,581 to 3,149.

Kidnappings surged from 7,324 to 10,925 in 2019 before dipping to 8,004 in 2020.

Thefts rose from 22,228 in 2016 to 34,970 in 2019 and were 31,971 in 2020.

Riots initially fell from 11,617 in 2016 to 7,262 in 2019 but rebounded to 9,419 by 2020.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Bihar ranked consistently among the top five states for violent crimes between 2017 and 2022.

Another revealing study, Dynamics of Circulation and Trade Networks of Illegal Firearms and Ammunition: A Bihar Perspective, conducted by Bihar Police, analysed State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) data from 2015 to 2024. It underscored the growing nexus between violent crimes and illegal arms trafficking.

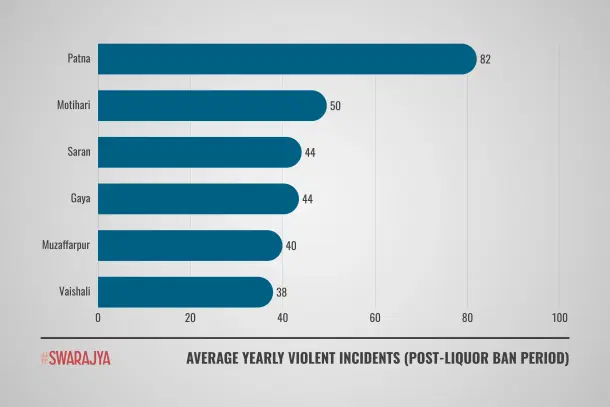

The study found that despite economic growth, Patna's crime landscape remains intense. The capital recorded an average of 82 violent incidents annually, the highest in Bihar. Other high-crime districts included Motihari (49.53), Saran (44.08), Gaya (43.50), Muzaffarpur (39.93), and Vaishali (37.90).

Strikingly, seven of the ten districts with the highest violent crime rates (Muzaffarpur, Nalanda, Samastipur, Patna, Begusarai, Vaishali, and Motihari) also ranked among the top ten for Arms Act violations, suggesting a direct link between firearm availability and violent crime.

The state's arms black market thrives on three main sources: country-made firearms from local illegal factories, diverted ammunition from legal stockpiles, and misappropriated licensed weapons. The scale of these operations paints a grim picture of a security system on the brink.

Annually, the state records an average of 2,913 Arms Act cases involving weapon seizures. Between 2015 and 2024, police recovered 3,628 illegal firearms and over 17,200 rounds of live ammunition.

These weapons are routinely used in crimes such as murder, extortion, highway dacoities, kidnappings, and theft.

With an average of 321.7 cases and 384.4 firearm recoveries per year, Patna leads in Arms Act violations. Other top districts include Begusarai (167.7), Muzaffarpur (158.3), Nalanda (117.9), and Vaishali (117.8). In firearm recoveries, Munger trails only Patna with a rate of 222.3 per year.

Patna and Munger are central to the over 100 per cent surge in country-made firearm seizures, which rose from 2,356 in 2015 to 4,981 in 2024.

Ammunition seizures followed suit, jumping from 9,449 rounds in 2015 to 23,451 in 2024. The 2023 peak saw 31,691 rounds recovered. Aurangabad topped the list for ammunition seizures, with Patna and Gaya following closely.

The more pressing concern is illegal gun manufacturing. In 2018, police discovered 13 such factories. By 2023, the number had skyrocketed by 330 per cent to 70, and in 2024, the figure remained alarmingly high at 64.

Munger is the epicentre of this problem, averaging 18.1 illegal gun factory busts per year—vastly outpacing second-ranked Nalanda with just 2.9. Other hotspots include Khagaria, Patna, and Bhagalpur.

This situation presents a severe headache for the Bihar Police. As the state's economy transforms (rural areas becoming semi-urban, and urban centres becoming more modern), the lethal combination of accessible firearms and frustrated youth in the 3 to 25 age group creates a volatile cocktail of violence and desperation.

Districts like Patna, Begusarai, Muzaffarpur, Vaishali, Bhagalpur, Nalanda, and Gaya are witnessing old security challenges re-emerge in new forms. Caste rivalries of the past are morphing into economic competition. As land ownership changes hands, from forward to backward castes and vice versa, conflict follows.

In the midst of such intense competition for resources, both within and between castes, state policies have steadily eroded the deterrent effect of law enforcement. For the poor, the police appear weak against powerful strongmen but overbearing towards them. This is a direct consequence of flawed recruitment systems and weak enforcement capacity.

Naturally, faith in the state's protective power erodes. The result is an unending cycle where everyone scrambles for power, because that is what survival demands in a state where weak governance is executed by even weaker agents under easily manipulated laws.

Some seek power through politics, others through wealth and land. Yet others find power in their capacity to eliminate rivals. In Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh, these avenues often converge in one class. Politicians.

The politicisation of state institutions has had devastating consequences in the past. For police veterans from the 1990s, the current situation evokes a sense of déjà vu. Passion crimes, extortion demands, kidnappings, business-related shootings—everything is back, albeit with somewhat less intensity.

This is what happens when government machinery is overly politicised. Bihar is now paying the price for short-term political gains having been prioritised over the long-term health of its institutions.

Politicians must remember that a state is not merely a political construct. It is a machine that requires careful calibration of functioning offices, safe environments, and forward-looking policies that empower rather than restrict.

This is Bihar's cautionary tale to the rest of the country. When individuals begin to treat society as an endless power struggle, the state descends into a race to the bottom.

No citizen should have to hear remarks like “The officers there don’t even look like police,” or “The criminal escapes while the police chase shadows.” But such is the perception when a state stops functioning as a state.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.