Books

2014: A Round-Up of Science - Questions and Answers

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 31, 2014, 04:15 PM | Updated May 02, 2016, 10:49 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

At the end of the year, we take a look at the way science was reported to the lay public by the popular monthly science magazine Scientific American.

The choice of the articles highlighted here are based more on the writer’s individual preference than the prominence given in the magazine.

January: Lithium wars brewing…

The United States’ Department of Energy had launched a Critical Materials Institute. Saleem H. Ali, director of the Center for Social Responsibility in Mining at the University of Queensland (Australia), comments in his article: “Unfortunately—like the original Manhattan Project—the program is driven more by the threat of international conflict than by ideals of scientific cooperation. The appropriation made it through Congress almost certainly because of legislators’ fear of China’s dominance in many critical elements and Bolivia’s ambition to become ‘the Saudi Arabia of lithium’.”

And here is the important point in the article: “Despite their name, rare earths are many times more common than gold or platinum and can be found in deposits around the world. In recent years, however, cheap labor and lax environmental regulation have enabled China to corner the global market, mining and refining of well over 90 per cent of rare earths.” Indians take note.

The magazine also produced a list of 10 most polluted places on earth. An earlier list compiled in 2006 featured India and China. But a new top 10 had emerged now. Although none of the sites listed are in developed countries like the US or Europe, a research from Green Cross, Switzerland, an organization involved in the study, pointed out that ‘much of the pollution stems from the lifestyles of wealthy countries’. For example, the tannery-town of Hazaribagh in Bangladesh is one of the top 10 toxic sites. It produces leather for high-fashion Italian shoes.

February: Chicken Ethics…

Science Agenda, the opinion column of the editors, asked for reduction of restrictions on research of drugs: ‘It’s time to let scientists study whether LSD, marijuana and ecstasy can ease psychiatric disorders.’

Chickens, it is discovered, are more intelligent than we thought. Carolyn L. Smith and Sarah L. Zielinski, in their article Brainy Bird wrote: “Taken together, these findings suggested the sounds did not simply reflect a bird’s internal state, such as “frightened” or “hungry.” Instead the chickens interpreted the significance of events and responded not by simple reflex but with well-thought-out actions. Chickens, it seems, think before they act—a trait more typically associated with large-brained mammals than with birds.” They then criticise the conditions of intensive poultry farming for both broilers and layers and say: “This type of farming will likely continue as long as most people are unconcerned about where their food comes from and unaware of chickens’ remarkable nature.”

March: Reductionism to Networks

The cover story is on the brain and Mariette Di Christina, editor-in-chief of the magazine makes the following interesting observation in her editorial comment:

Now we are moving into a new era, one that will be less marked by (of necessity, given the tools that have been available) the reductionist strategy of trying to understand the role of this or that chunk of brain tissue and more by a network-focused understanding of the complex systems involved in any activity.

Science Agenda called for more benign treatment of some of the planet’s largest animals kept in captivity by humanity for entertainment purposes. These animals have a conception of the self and confinements damage these animals not just physically but also psychologically:

As with chimps, the intelligence of orcas and elephants is undeniable. Boasting some of the most intricate brains around, all three animals have recognized themselves in mirrors, indicating that they, too, have a concept of self…Captive orcas are unusually aggressive, biting and ramming one another as well as trainers. Many researchers think the animals behave this way because they are so stressed; some have suggested that longtime confinement makes cetaceans psychotic.

In a relatively short column, David Pogue revisits the techno-social predictions for 2014 made by the great science-fiction author Isaac Asimov in 1964. They fall into three categories: where he got them right (self-driven cars, video calling, single-duty household robots etc.); where he got them wrong (like underwater housing); and technological progresses which are feasible but not tried for want of courage (like lunar colonies).

In 1964, Asimov’s estimate of the global population in 2014 was 6.5 billion. The actual figure? 7.1 billion. Amazingly close, one should say!

April: Spiritual Calculus

Our digital communication gadgets use components made from so-called conflict minerals—gold, tantalium, tin and tungsten—taken from specific mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo. DRC is undergoing a civil war, and this commerce ends up financing specific armed groups that control the area of mining. Already, chip makers like Intel have declared that their chips are free of ‘conflict minerals’. Further stringent regulations are being brought in on the trade of these material.

Again this is something that has lessons for India—the armed conflicts centring around mineral-rich regions in India may have larger impacts and coming together of strange partners as string pullers.

The cover story—Cosmic Dawn: How the First Stars Ended the Dark Ages of the Universe—asks an interesting question. About 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe started cooling, allowing hydrogen atoms to get formed. And that was also when the cosmos went dark. It was one billion years later that ‘reionization’ paved the way for light to reappear. So which objects powered the ‘reionization’? Quasars? It is an interesting quest.

Another important article in this issue by Amir Alexander—The Secret Spiritual History of Calculus—shows how the innovation of Italian mathematician Bonaventura Cavalieri, ‘the method of indivisibles’, which was the forerunner of integral calculus, was attacked by Swiss mathematician Paul Guldin for theological reasons. This new insight into the 17th century debate shows how theology interacted with the method of science in the late pre-modern Europe.

May: Expanding Equations of Ramanujan

This month the magazine carried two articles important from the Indian point of view. One is about the fast disappearing coral reefs across the world due to global warming. J.E.N. Veron, former chief scientist of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, is credited with discovering more than 20 per cent of the world’s coral species. An adapted preview from The Reef: A Passionate History, by Iain McCalman, the article informs the readers how now Veron is worried about the fast coral bleaching and death which is because of the acidification of the oceans due to climate change along with increasing ocean temperatures. The coral richness of Indian eastern coast also harbours in it the Gulf of Mannar, a marine biodiversity hotspot whose fishing waters are already embroiled in geopolitical and community conflicts. Coral depletion here would really mean livelihood as well as ecological disasters. This is an issue we need to take care of.

The article on Srinivasa Ramanujan by Ariel Bleicher elaborates how mathematician Ken Ono solved long-standing puzzles using insights hidden in the unpublished papers of the Indian prodigy. Here is an excerpt: ‘Because Ramanujan did not record proofs, Ono could not directly identify errors in the prodigy’s thought process. So he decided to plug some numbers into the formulas Ramanujan included in the statements, hoping these examples might reveal some laws. Yet the formulas worked every time. “Holy cow!” Ono said to himself. He realized that Ramanujan had to be right “because you couldn’t possibly be creative enough to make something like that up and have it be true 100 times unless you knew why that formula was true, always.” Then he closed his eyes and thought hard about what Ramanujan understood that no one else had.”

June: Martian Microbes

Ever since the meteorite ALH84001 was discovered in Antarctica in 1984, the possibility of Martian microbial life has been high in the pop-sci psyche. The article How to Search for Life on Mars speaks about the near-future missions to Mars which are going to conduct biological tests for the trace of existing or extinct Martian microbial life. It is indeed astonishing to know that no mission to Mars has searched for life since the Viking programme in the 1970s.

Brendan Borrell’s Seeds of a Cure looks at how traditional herbal systems of knowledge are being now studied with renewed interest. Borrell points out that while ‘many US Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs have their origins in the natural world, running a clinical trial with a traditional herbal medicine falls outside mainstream practice.

As the story unfolds through the work of Bertrand Graz of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and Merlin Willcox of the University of Oxford studying the herbal solutions, Borrell remarks that ‘their approach, called reverse pharmacology, was inspired by the efforts of Indian scientists hunting for new drugs from ancient Ayurvedic medicine.’ Now that makes one wonder why Indian media has been stunningly silent about this interesting endeavour by Indian scientists. As the article ends we read that ‘in 2010, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria terminated $18 million in malaria grants over charges of corruption, and in 2012 the fund announced it was shuttering the Affordable Medicines Facility, which has provided subsidies to importers to help get reliable drugs into village shops. Willcox and Graz had plans to measure the public health impact of their A. mexicana recommendations, but the tenuous political situation put them on hold.”

If this is now, then just imagine what would have transpired during the colonial era…

July: Thin line between Self-Help and Self-Delusion

Neuroscience journalist Maia Szalavitz’s When Does Self-Help Actually Help? comes with a curious tagline: ‘Dangers lurk within the US’s $12-billion self-help industry.’ Here is an excerpt: ‘Add physical and emotional stress to peer pressure, and you have a potentially more dangerous brew. Seminars…known among psychologists as “large-group awareness trainings”…can include vague promises about self-improvement, a charismatic leader generally guides a group of people through several continuous days of meditation, self-hypnosis, fasting, sermons and discussions in which they share intimate details about their lives. All the while, the leader alternately rebukes and praises the participants—and denies them basic needs—to leave them psychologically vulnerable.’

Many modern guru-based Yoga circuits may fit the above description. In that case, Indian Yoga gurus need to come together and create some sound guidelines for their camps. The following cautionary notes Szalavitz provides may help in formulating such a code: ‘First, overcoming depression, anxiety, addictions or other disorders typically requires learning new coping skills over many months or years, not in a matter of days or weeks…Second, good programs have independent data showing their effectiveness, not just anecdotes…If there is no published literature supporting a program—no matter how popular it may be—that is a red flag…Ultimately, of course, looking for a signature on a safety pledge is no substitute for doing your homework, checking out scientific claims and maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism.’

August: Epigenetic inheritance

This may be the most disturbing article in the magazine. A New Kind of Inheritance by Michael K. Skinner is about how epigenetic factors can be harmed by pollutants, stress, diet and other environmental issues, and the some of these acquired changes can be passed on to descendants.

Here is an excerpt: ‘About 13 years ago, Andrea Cupp and I, with a few of our colleagues at Washington State University, were using rats to study the reproductive effects of two chemicals widely applied in farming—the pesticide methoxychlor and the fungicide vinclozolin…We had injected the chemicals into pregnant rats during the second week of gestation—when the embryo’s gonads develop—and saw that nearly all male offspring grew up to have abnormal testes that make weak sperm and too few of them…But one day Cupp came into my office to apologize: by mistake, she had mated unrelated male and female pups from that experiment. I told her to check the grandchildren of the exposed dams for defects, although I did not expect she would find any…As the great-grandchildren—and later the great-great-grandchildren—matured, the males of each generation suffered problems similar to those of their ancestors. All these changes stemmed from a fleeting (but unnaturally high) dose of agricultural chemicals that for decades were sprayed on fruits, vegetables, vineyards and golf courses.’

One shudders to think about the epigenetic defect possibilities that may be running down the line in the Indian population with such uncontrolled pumping of pesticides and chemical fertilizers into our food webs. Epigenetic factors play such a decisive role that we even have to change our conception of evolutionary mechanism. Says Skinner:

‘If the environment can sometimes directly produce long-term trans-generational changes in gene activity without first altering the DNA coding sequence, then the classical view of evolution—as a slow product of random mutations that get “selected” because of the reproductive or survival advantage they offer—will have to be expanded. It is even conceivable that epigenetic inheritance could explain why new species emerge more often than one would expect, given the rarity of advantageous genetic mutations.’

Another intriguing article in this issue is about the acquired inner savant. The savant syndrome is one in which people with autism display extreme artistic talents. When the phenomenon emerges in people who have undergone trauma, it is called ‘acquired inner savant’. Based on his work with such ‘savants’ from 1962 onwards, psychiatrist Darold A. Treffert argues that most of us may carry an inner savant. That phenomenon may be activated by stimulating specific brain circuits. This he says can either be achieved through electrical stimulation or focused practice (Accidental Genius).

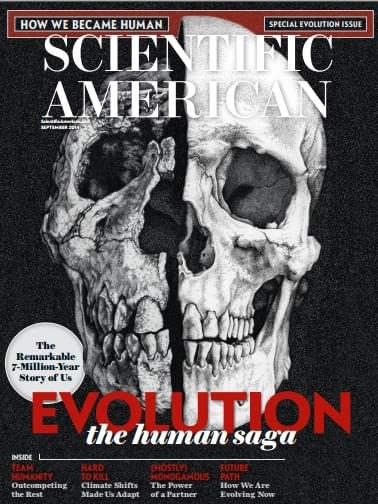

September: Evolved, evolving and will evolve

The cover story is about the new discoveries that are changing the way we have so far understood human evolution. It had been a straight simplistic story from Australopithecus to Homo Sapiens. But there were inner branches that went extinct. The evolution of the human species is becoming more and more complicated as well as exciting as our techniques get sharper and more powerful. A veritable kaleidoscopic interplay of climatic changes and genetic as well as cultural factors in fragmented early humans resulted in the emergence of our species, a new theory claims.

Another article shows that even the first hominins that emerged were monogamous and monogamy had definitely evolutionary advantages in making the human species what we are. In discussing what makes us specially humans, a study is cited which shows that chimps and young children perform equally on tests of capacities measured by conventional IQ tests related to spatial and quantitative abilities.

But children do better on cognitive tests related to social skills, such as learning from others. Or, in other words, social empathy is a key factor that favoured the unique inner and social development of humans.

We are still an evolving species. Anthropologist John Hawks has this to say about the ongoing human evolution:

‘Across the past few thousand years, human evolution has taken a distinctive path in different populations, yet has maintained surprising commonality. New adaptive mutations may have elbowed their way into human populations, but they have not muscled out the old versions of genes. Instead the old, “ancestral” versions of genes mostly have remained with us. Meanwhile millions of people are moving between nations every year, leading to an unprecedented rate of genetic exchanges and mixture.’

Again in line with the mounting evidence of intelligence and cognition in non-human animals (and birds). But this time it is not just cognition. Thinking about thinking is called metacognition. And guess where the scientists discovered this supposedly unique human ability? Western scrub jays—cute little birds that have indicated that they may have the ability for metacognition in an experiment designed by Arii Watanabe of the University of Cambridge. If conclusively proved, then there are implications galore. That is a small note in this one-issue magazine that concentrates on human evolution.

October: When a sceptic becomes empathic…

In its report on the state of world science, Prof. Katherine W. Phillips makes the following point:

‘Decades of research by organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists and demographers show that socially diverse groups (that is, those with a diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation) are more innovative than homogeneous groups.’

She says that ‘being around people who are different from us makes us more creative, more diligent and harder-working.’ An interesting observation, given the fact that India has such diverse social groups coming to interact in trades that necessitate creativity. This may well be the rationale for the caste system. While maintaining the cultural diversity of various social groups, the genetic barriers between them have to be erased as they would be when they get together on a creative mission. On the other hand, the much flaunted efficiency of homogenous social groups engaged in a particular occupation while showing outward signs of robust efficiency may be actually strangling creative advances in that occupation, both at the level of technological innovation and organizational adaptability to a changing environment.

A very important piece in this issue is Lisa Margonelli’s An Inconvenient Ice. This is about methane hydrates which are abundant along the coastal sea floors of many countries including India. The article observes:

‘Japan leads the small but significant international race to develop hydrates for energy, spending $120 million on research last year. In 2010 the US invested about $20 million, but by 2013 that had fallen to just $5 million. Germany, Taiwan, Korea, China and India have small research programs.’

The hydrates may have the capacity to replace all coal and petroleum but they may also release greenhouse gases.

In his regular column Skeptic, Michael Shermer usually offers rational explanations for so-called paranormal phenomena and psychological reasons for belief in them. However, this month’s column was different. He almost betrays a tendency to believe in the paranormal when an emotionally laden coincidence happens. Shermer goes: ‘Jennifer is as skeptical as I am when it comes to paranormal and supernatural phenomena. Yet the eerie conjunction of these deeply evocative events gave her the distinct feeling that her grandfather was there and that the music was his gift of approval. I have to admit, it rocked me back on my heels and shook my skepticism to its core as well. I savored the experience more than the explanation.’

It is hard to believe that it is Michael Shermer in Scientific American, for it reads it is an emotion-drenched columnist in Reader’s Digest. Sceptic with an empathic heart, Mr Shermer?

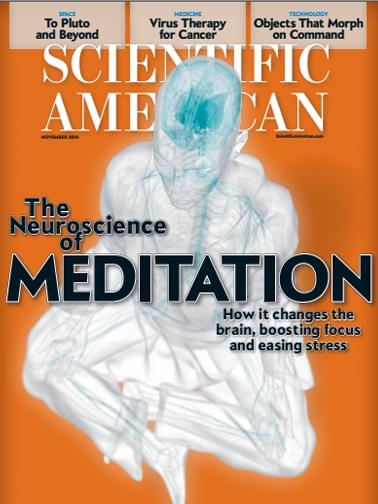

November: Meditation and Yoga

Written by French Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard and neuroscientists Antoine Lutz and Richard Davidson, the cover story Mind of the Meditator shows how meditation creates changes in the brain to improve focus and reduce stress. The article states: ‘Contemplative practices that extend back thousands of years show a multitude of benefits for both body and mind.’

For long, the West has been fascinated with Yoga and meditation as health techniques to be integrated with the fast-life culture of consumerist society. Reduction in stress to increase in attention to many correlated physiological and psychological benefits, are discussed in the article. This is not the first time Scientific American has published a positive feature on meditation techniques. In 2013, its sister publication Scientific American Mind had an article by Christof Koch, The Brain of Buddha, which was about the scientific study of Buddhist meditation along with an interaction with His Holiness Dalai Lama. Here Koch speaks about a study conducted on ‘the Buddhist mind-calming practice called shamatha and also refers to a 2008 study by Richard J. Davidson and his group at the University of Wisconsin–Madison which was done with active participation of Buddhist monks.

One would like to ponder why, despite many non-Buddhist Hindu gurus building big empires out of Yoga techniques in the West, that it is Buddhism that has engaged in active dialogue between meditation and neuroscience? Yes, TM (Transcendental Meditation) once created a huge wave and research interest. Even the discredited Nityananda trumpets some research findings. But these are still within the cult atmosphere while Buddhism—despite the presence of cultists there—has stolen a march over the non-Buddhist Hindu gurus in having a constructive dialogue with science. Perhaps with Modi’s Indic reclaiming of Yoga on the international stage, things may change.

The Indian Supreme Court soliciting comment from its state governments to examine the right to die for terminally ill patients made it to the ‘quick hits’ infographics of this month’s issue.

December: Does the future of medicine have an Eastern flavor?

The feature on chronic pain makes the following very interesting observation:

‘The future of medicine, most researchers believe, is personalized. For chronic pain, that future is only just coming into view. Treatment at even the best centers tends to rely largely on trial and error.(Stephani Sutherland, The Pain That Won’t Quit). In a related box-feature, Mark Peplow points out that venom molecules can be used in the future to treat pain: ‘The Chinese red-headed centipede’s toxic venom contains a component that can numb nerves without harming the rest of the body.’

Personalized medicine for chronic pain is something that has been inherent in eastern medicinal systems. In an article by Helene M Langevin in the magazine The Scientist last year (The Science of Stretch, 1 May 2013), the author, a clinical endocrinologist suffering from chronic pain, turns to acupuncture, gets relief and then studies it. She observes that there is a strong correlation between connective tissues and the meridians of acupuncture. Her study found that more than 80 per cent of acupuncture points in the arm are located along connective-tissue planes.

Perhaps Indic medical systems should also take into account these new developments and adapt as well as update their repository of knowledge as new frontiers open up.

Michael Shermer’s Conspiracy Central is a must-read. Here the columnist tries to understand the psychology of people who believe in conspiracy theories and why. He states: ‘Group identity is also a factor. African-Americans are more likely to believe that the CIA planted crack cocaine in inner-city neighborhoods. White Americans are more likely to believe that the government is conspiring to tax the rich to support welfare queens and turn the country into a socialist utopia.’

Well…the Indian political milieu has its own conspiracy theorists. People who believe RSS-Hindutva forces were behind 26/11 even have political respectability. One famous Tamil Islamic blogger once commented on a Tamil website that Shias were the product of a Jewish-Brahminical conspiracy to thwart the growth of Islam. Some fringe Hindutva groups too believe in conspiracy theories—missionary conspiracies to the Illuminati. So Shermer’s article is as relevant to the Indian environment as it is to the US—just change the particulars but the principles remain the same.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.