Books

How Historian Meenakshi Jain Brings Raja Bhoja Back To Life In Her Latest

R Jagannathan

Oct 07, 2025, 12:50 PM | Updated Oct 16, 2025, 03:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

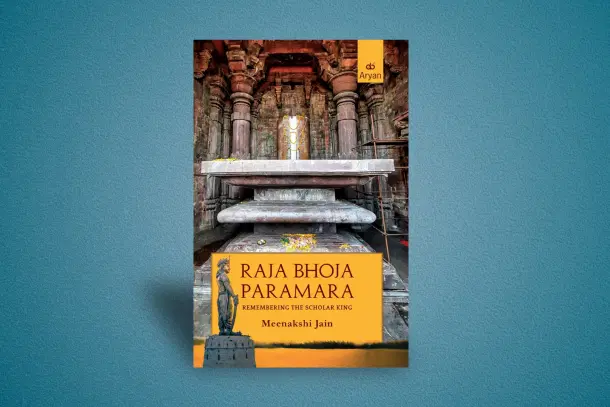

RAJA BHOJA PARMARA: Remembering the Scholar King. Meenakshi Jain. Aryan Books. Price: Rs 595. Pages: 162.

One of the problems with secular history writing has been that its primary purpose has been to whitewash some unsavoury portions of our past in order to build a narrative about Ganga-Jamni tehzeeb for post-partition India. In the process, a disproportionate share of Leftist history writing has focused on certain aspects of Islamic rule that served their purposes while glossing over larger portions of Indian history with Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist overtones.

In recent years, many attempts have been made to correct this imbalance by highlighting unsung rulers who were either edited out of Bharat’s history or given very short and dismissive coverage in history books written by the Left-secular consensus. Secular writing also failed to emphasise the damage done by colonial historiography, which tended to downplay India’s own historical memories and achievements while exaggerating blemishes such as the practice of sati in certain regions.

One historian who has repeatedly sought to correct this imbalance is Meenakshi Jain. Her previous books on Sati, Rama and Ayodhya, Vasudev Krishna and Mathura, Vishwanath Rises and Rises, and The British Makeover of India have been widely acclaimed. Her latest work, Raja Bhoja Paramara: Remembering the Scholar-King, highlights the remarkable architectural and literary achievements of this 11th-century ruler of the Malwa region, shedding light on one of the less remembered titans of our Dharmic past.

In this slim volume, richly illustrated with pictures and appendices, Jain focuses on Raja Bhoja, famous for his Bhojshala in Dhar, which was overlaid by a mosque (Kamal Maula) during Islamic rule. The Bhojshala is now a source of communal friction in Madhya Pradesh due to a court case seeking the restoration of its original status. A 2,000-page Archaeological Survey of India report submitted to the Madhya Pradesh High Court confirmed that the mosque was constructed over an 11th-century structure built during Raja Bhoja’s reign using temple parts.

At first glance, this seems to be a story that repeated often during Islamic rule. However, the real value of Jain’s work is not what happened to the Bhojshala in the 13th century, but the history of the dynasty’s contributions over five centuries. The book chronicles the rise and eclipse of the Paramaras, who had several branches: one ruling from Bhinmal in western Rajasthan, another from Jalor, and yet another from the hilly parts of Mewar. The fourth Paramara dynasty, founded by Upendraraja in Malwa (dated between 791 and 818 CE), is the primary focus. This dynasty ruled for nearly five centuries, reaching its peak under Raja Bhoja in the 11th century.

The Paramara legend traces its origin to an angikula yajna performed by Rishi Vasistha. Though Sage Vasistha appears in the Ramayana, his re-emergence is linked to a yajna performed at Mt Abu to regenerate the warrior class among the people of the land. This occurred when Arab and Turkish invasions threatened northern India towards the end of the eighth century CE. According to the legend, the yajna produced four warrior communities, with the “fire-born” Rajputs giving rise to the Pratiharas, Paramaras, Chalukyas, and Chahamanas. The turbulent political situation apparently forced some Brahmins to give up priestly duties and become Kshatriyas. Jain suggests that the Paramaras were probably “Vasistha Brahmins”, as their gotra is still said to be Vasistha.

The book’s eight chapters begin with a brief introduction, followed by the Agnikula yajna legend and a description of the political situation after the fall of the Gupta empire. The Paramara history begins in the fourth chapter, and Raja Bhoja emerges prominently in the fifth.

The sixth and seventh chapters describe Raja Bhoja’s architectural legacy and his role as a patron of learning, noting that he was a poet himself. The final chapter discusses the aftermath of Bhoja’s reign, who ruled for 44 years (1011–1055 CE).

Raja Bhoja’s capital was Dhar, although the early Paramaras had Ujjaini as their capital. He is credited with building 104 temples, with the Bhojshala of Dhar being his most celebrated architectural achievement. Bhoja is also recognised as a poet-scholar, whose literary works were appreciated by later writers such as Bilhana and Kalhana. Among the many works attributed to him, his Sarasvatikanthabharana, an important text on Sanskrit grammar, is particularly notable.

This slim volume on Raja Bhoja brings attention to the lesser-commented aspects of Indian historical figures, and Jain must be commended for this effort. Her style is matter-of-fact and authentic. She avoids conjecture and vague theorising, and where inference is necessary based on known sources, she does not pretend otherwise. This careful approach makes her one of India’s foremost historians today, with factual rigour that is never overshadowed by flights of imagination.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.