Culture

Agastya: A Harappan-Vedic Seer Mystery

Aravindan Neelakandan

Mar 05, 2025, 08:12 PM | Updated Apr 02, 2025, 02:40 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Agastya is a name that emerges from the very dawn of Indian civilisation. It is a name that is venerated and celebrated throughout India and yet shrouded in mystery.

Born, as the sacred lore has it, from a pot (kumbha or kuda), this sage depicted as physically diminutive, is known affectionately in southern India as Kuru-Muni.

Though physically dwarfish, he possessed wisdom as vast as the ocean. A householder and a Rishi, the presence and influence of Agastya permeate all core aspects of Indian culture, particularly in southern India.

He is credited with shaping the very structure of the Tamil language, his name linked to the sacred origins of the Cauvery River. His musical prowess is remembered as matchless. Treatises of traditional medicine and the works on Siddha philosophy often bear his name, testament to his profound impact on indigenous knowledge.

For children raised in the Saivite tradition, he is a cherished friend; for spiritual seekers, a never-failing mystic guiding light.

Yet, despite this intimate familiarity, Agastya or Agathiyar as he is called in Tamil, eludes the grasp of a historian.

Who, precisely, was Agastya?

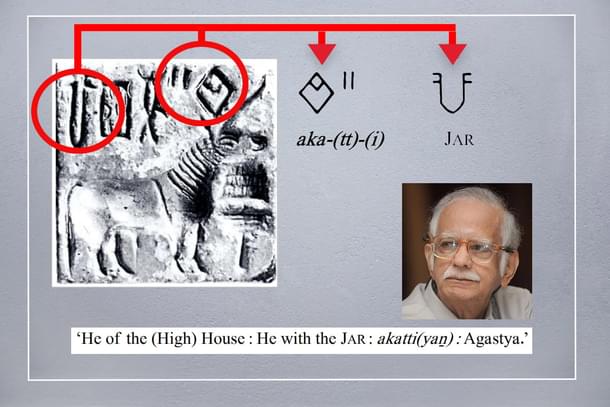

This question, a puzzle for academicians, might find a key in the work of Iravatham Mahadevan (1930-2018), a lifelong scholar of Harappan seal signs.

He labels the most frequently occurring sign at the beginning of any Harappan sign sequence as ‘alpha.’ Of course ‘omega’ is the highest frequency sign that occurs as the terminal sign.

According to Mahadevan, the ‘alpha’ sign showing an enclosure may relate to aka-tt-i ‘he of the (High) House’ and ‘was the prototype of Indo-Aryan Agasti (Agastya) as well as Dravidian Akatti (Akattiyan) of the Old Tamil legends (who led the southern migration of the Vel|ir and other tribes from Dwaraka in the Gujarat region to the southern peninsula).’

The omega sign is hypothesised by him to have functioned as masculine singular grammatical sign and also as an ideogram for ‘jar born’. So Mahadevan concludes that the ‘alpha’ and ‘omega’ signs might actually mean ‘He of the (High) House : He with the jar: akatti(yan): Agastya’. (Iravatam Mahadevan, Meluhha and Agastya: Alpha and Omega of the Indus Script, 2009).

Mahadevan posits that the figure of Agastya, potentially tracing its lineage to Harappan priestly leaders, embodies a complex confluence of traditions.

The epithet "He with the Jar" echoes the Rig Vedic narrative of his birth, shared with Vasishta, from the seminal vessel of Mitra and Varuna, a genesis attributed to the will of Urvashi (Rig Veda:7.33.10-11) .

Concurrently, Mahadevan suggests a Dravidian etymological root in 'Akaithiyar,' wherein 'Akathi' signifies 'one within the house,' though the precise origins of this term remain intricate and layered.

K.S. Srinivasan, a great scholar of Indian literature, points out the following when discussing the word in the context of Sangham literary taxonomy of ‘Akham’ poetry, which chiefly is about the inner life of romance and union of the hero and the heroine. He says:

The Dravidian Etymological Dictionary gives the meaning as 'inside, house, breast, place, mind' none of which is tantamount to the sense which Aham songs indicate. Besides, the DED does not cite any cognate word for aham in any of the other languages of the Dravidian group. On the other hand, the word aggam in Pali does have the meaning of 'house, shelter', (the sense in which 'aggaharram' is used in Tamil, to denote a row of houses).The Ethos of Indian Literature: a Study of Its Romantic Tradition, 1958, p.56)

Linguistic classification places Pali firmly within the Indo-Aryan language family. This naturally prompts the question: how, then, does the term ‘Akam/Akham’ come to be associated with the intimate sphere of love in Sangam literature?

A defining characteristic of this literary genre is its eschewal of named heroes and heroines. Instead, the lovers, depicted across various stages of their romance, serve as archetypes, a stark contrast to the ‘Puram’ genre, which meticulously records the names of individual chieftains and warriors.

One might draw a comparison to ‘Aham,’ a term of supposed Indo-European and definitely Sanskritic, signifying the self. The realization of this self, Moksha, represents the fourth and ultimate Purushaartha. In Tamil, this concept finds its counterpart in ‘Veedu,’ which, notably, also translates to 'home,' mirroring the meaning of ‘Akham/Akam.’

It is crucial to recall that later Bhakti saint-poets frequently employed the ‘Akham’ poetic form to express their devotion and union with the divine, a state that also signifies the realization of the Self – a concept closely aligned with the Sanskritic ‘Aham.’

It is within this framework, then, that the Agastya-Akathiyar connection should be understood. Rather than reinforcing a simplistic Dravidian-Aryan dichotomy, the term illuminates a profound cultural and spiritual unity.

Thiru Ra. Ganapathi (1935-2012), a distinguished writer of Dharmic literature in Tamil, in a posthumously published work on Agastya, further elucidates this point. He draws attention to Agastya's diminutive stature, linking it to the Kathopanishad's description of the Self as being the size of a thumb, residing within the body.

Indeed, the Kathopanishad's depiction of the thumb-sized Self is inextricably linked to two profound aspects: its indwelling within the body, and its nature as a smokeless fire ('ज्योतिरिवाधूमकः')—pure consciousness, the true Self unburdened by shadows (2.1.12 & 2.1.13).

This convergence of concepts finds a striking echo in the Tamil designation of Agastya, Aga-thi(i), "the one who resides in the house (Akha) as fire (thii)," suggesting a deliberate, perhaps divinely inspired, linguistic and philosophical integration.

The previously elucidated meaning of Agastya gains further corroboration through the verses of Saint Thirumoolar's Thirumanthiram. In this sacred text, the well-known Puranic episode of Agastya's dispatch to the south by Shiva, during the divine confluence of Shiva and Parvati, is depicted.

Thirumoolar, within the southern Indian Saiva lineage, is renowned for his adeptness at revealing the yogic and spiritual symbolism embedded within the Puranas.

Swayed from the Centre the Earth descends into disorder. Save us our Lord’ cried the celestials. Siva said, ‘Agastya of Centred Fire, quickly set forth thee to bring the order.’Thirumanthiram: verse 337 Irandaam Tantiram: Agatiyam:1

Agastya who nurtures the dawn fire, He who with the celestial fire traversing the day primordial born mystic seer of the North, the light radiant itself that nurtures everywhere.Thirumanthiram: verse 338 Irandaam Tantiram: Agatiyam:2

Both the verses show the real nature of Agastya and resonate well with the ideational nature of the seer.

Dr. Pa. Arunachalam, who was a Tamil scholar from Malaysia University in his commentary on Thirumanthiram explains:

Thirumanthiram shows Agastya as Yogi par excellence. The symbolism encoded here is that when balance is lost in Yoga Sadhana then Agastya comes to the rescue... 'Fire of the Centre Agastya' can be only taken as the 'Agastya capable of directing Kundalini in the middle path'. Further Agastya is referred as 'one nurturing the dawn fire' or the Surya Nadi... One side the Surya Nadi and the other side Chandra Nadi (Ida and Pingala). In between, central is the Sushumna. When Agastya is said as the one of central fire, does not it map to Agastya as the one who channelises Kundalini to through the central path. Then balancing becomes here the balancing the path of Yoga. ... Param Yogi Siva is anchored in the Centre. Naturally His devotee Agastya too is centred seer. It is through him that the world should get balance. ... Here the balanced centre is defined through the experience of Yoga.

Consequently, a comprehensive vision emerges, wherein seemingly disparate elements find their unity within a tradition that bridges millennia.

Iravatham Mahadevan draws our attention to another intriguing detail, found within the ‘Puram’ song-201.

This Sangam verse references a seer as the patriarch of the ancient Tamil clan, the Velir. The poet Kabilar recounts how a Tamil king ruled a place of copper fortresses called ‘Thuvarai’ for 49 generations. This clan's progenitor is described as a "northern seer" who emerged from ‘Tadavu.’

U.Ve. Swaminatha Iyer interpreted this as a later legend of ‘Sambu Muni,’ identifying ‘Thuvarai’ as Dwaragasamudram, the medieval Hoysala capital. Mahadevan, however, refutes this identification. He rightly recognizes ‘Tadavu’ as a variant of ‘Tada,’ meaning a water pot. In Sanskrit this is 'Tadakam'. Furthermore, he aligns ‘Thuvarai’ with Dwaraka, corroborating this with a 'luckily preserved' legend by Nachinarkiniyar, the renowned 13th-century Tamil scholar, in his commentary on Tholkappiyam.

This legend recounts that Agastya, in the aftermath of the earth's tilting during a gathering of gods around Mount Meru, guided Krishna's descendants—including 18 kings, 18 Velar, and Aruvalar—to the south.

There, they transformed forested regions into fertile agricultural lands, constructing irrigation channels and other vital infrastructure. Mahadevan then asserts that these 'Venthan-Velir-Vellalar clans constituted the ruling and land-owning categories since the beginning of recorded history and betray no trace whatever of an Indo-Aryan linguistic ancestry.’

Consequently, he argues that Agastya's leadership of the Velir definitively 'rules out the possibility that he (Agastya) was even in origin an Aryan sage.' This assertion is made despite Mahadevan's own acknowledgment that, within his Northern-Aryan-Dravidian framework, Tamils were under 'religious and cultural influence of the north' well before the Sangam era. It appears, however, that Mahadevan's reasoning here contains a flaw rooted in his Aryan-Dravidian binary perception.

To understand that one has to look deep into the Rig Vedic hymns revealed by Agastya, which manifest a core aspect of Vedic spirituality.

In the first Mandala, the 165th hymn, attributed to Agastya, depicts Indra asserting his exclusive right to all Yajna honours. He refuses to share them with the Maruts, the storm gods. These hymns reveal a monopolistic claim to devotion and ritual: 'May the prowess of me alone be irresistible; may I quickly accomplish whatever I contemplate in my mind; for verily, Maruts, I am fierce and sagacious and to whatever (objects) I direct (my thoughts), of them I am the lord, and rule (over them) (I.165.10).

However, Agastya then praises the Maruts, whom Indra considers inferior and rivals: 'This praise, Maruts, is for you; this hymn is for you, and is made by a respected singer. May the praise reach you, so that we may obtain food, strength, and long life (I.165.15)'.

In the subsequent sukta, comprising 15 hymns, Agastya offers varied praise to the Maruts. This pattern continues in the following sukta, with the penultimate hymn also praising Indra. Now, the 170th sukta of the first Mandala emerges as particularly significant within this dramatic sequence.

Indra expresses his discontent to Agastya, perturbed by the Rishi's praise of the Maruts. Agastya, with gentle persuasion, implores Indra to relinquish his hostility towards the storm gods, urging him to share the offerings of praise and ritual bestowed by humankind. "They are your brothers in divinity," Agastya reminds Indra. Indra, in turn, acknowledges Agastya as his brother, though he reveals that he doubts Agastya that the seer might withhold Indra's share of the Yajna.

Yet, Agastya, embodying a spirit of inclusivity, champions the recognition and praise of the Divine in its manifold forms. He declares:

Let the priests decorate the altar; let them kindle the fire to the east; and then let us both consummate the sacrifice, the inspirer of immortal wisdom. As Vasupati, Thou art the lord of riches; As, Mitrapati, Thou art the firm stay of us your friends; declare your acceptance (of our offering), Indra, along with the Maruts, and partake of the ‘ṛtuthā havīṃṣi'.Rig Veda. I.170.4-5

Agastya, with profound wisdom, invokes both Indra and the Maruts, offering praise to each. He skilfully persuades Indra to embrace the sharing of divine honours, rather than claiming exclusive veneration. This act of reconciliation, rather than the establishment of a singular, jealous deity, marks the sukta's significance.

A monopolistic Indra-experience offers Agastya the mantle of exclusive prophethood. He is called by Indra as his own brother. So the divine authority is conferred. At this moment, Agastya could have easily become the chosen mouthpiece of a singular, jealous, mighty Indra. But Agastya embraces the Rishi-Muni tradition of Vedic civilization. Agastya Muni chooses to ensure the Divine is adored and realised through infinite forms, thus establishing the civilisational foundation for theo-diversity.

Agastya's Vedic relationship with the Maruts and Indra acquires notable importance in the southern Indian context. Mahadevan's legend of Agastya leading the Velir's agricultural expansion into the region gains symbolic depth when considered alongside the Tamil eco-cultural categorisation.

The deity of the agricultural Maruta-land is Indra called 'Venthan'. The resonance between the words Indra (Tamil: Inthiran) and 'Venthan' should also make one rethink the assigning of any pure isolated linguistic ancestry to the word.

Later Buddhist work in Tamil, the Manimekalai, recounts Agastya's counsel to a Chola king to establish Indra celebrations in Poompuhar, ensuring the prosperity of the nation. The convergence of Maruts and Indra in Tamil land and Agastya's own samanvaya between Indra and Maruts shows a deeper cultural continuity here.

Evidence recently published in Science (Heggarty et al, 2023) proposes the possible presence of Indo-European languages within the Harappan and peripheral Harappan areas during its flourishing phase. This suggests the Harappan civilization was likely a multi-ethnic, multilingual, and theo-diverse society. In this civilizlational evolution, Agastya likely served as both a sacred ritualistic figure and a symbolic seer of syncretism. He has also been always a symbol of inner consciousness - the Self. These elements are intricately interlinked, reflecting a pattern seen in many core life processes of Indian tradition.

It is within this framework that we can understand the narrative of Agastya acquiring Tamil from Shiva or Muruga and subsequently shaping its grammar.

India, in its profound intellectual tradition, has cultivated a unified linguistic Darshana. This Darshana explores the intricate relationship between language and consciousness, tracing the emergence of words from the depths of the psyche and examining the interplay between word and meaning. This profound connection imbues language with an inherent sacredness.

Agastya, in this context, emerges as a symbol of this Darshana in the South. His role transcends the conventional boundaries of any specific language, such as Sanskrit or Tamil, and speaks to a deeper understanding of the science of language. Madava Sivagnana Munivar, in his eighteenth-century Tamil classic, eloquently expressed this concept in Puranic language, stating that Tamil grammar emanated from the damaru of Shiva and was bestowed upon Agastya.

Thus, delving into the enigma of Agastya, much like the Puranic lore surrounding him, serves to purify our intellect, liberating us from the divisive and conflict-ridden binaries of half-truths. It guides us towards a holistic and empirically grounded vision of our past, one that embraces through samanvaya and sadhana, complexity, interconnectedness and spiritual evolution.