Culture

Dushyanth Sridhar's Ramayanam: A Modern Masala

Keerthivasan Ramachandran

Aug 08, 2024, 11:28 AM | Updated Sep 05, 2024, 11:51 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

.webp?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

.webp?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

I acknowledge Dr R Rangan with whom I discussed before penning this essay. (Dr R Rangan is a well-known Ramayana discourser and the author of the ten volume translation of Valmiki Ramayana with a comparative analysis of various Ramayanas of most Indian languages.)

Sculptures

Shri Dushyanth Sridhar’s “Ramayanam, Volume 1” (HarperCollins Publishers, 2024) contains pictures of various sculptures related to various events of Ramayana and Purana stories. Their location and age are also mentioned. This collection is highly appreciable.

Shri Dushyanth’s Preface: A Critical Review

“No English retelling… to the best of my knowledge, has covered the purpose of pairing the original with its commentaries, as much as this book does” says Shri Duhsyanth in his preface. He may be correct regarding the abridged retellings.

But before making this high claim he should have referred to the brilliant English translations of Ramayana like those of Shri Keerthanacharya C.R. Sreenivasa Ayyangar, named “The Ramayana of Valmeeki, rendered into English, with exhaustive notes” (M.K. press, A.L.V. press & Guardian press, Madras, 1910) and Vidvan Gaurangadas (Rupa Raghunatha Vani publications, 2019). These books are more scholarly and abundant with commentaries and references.

Shri Dushyanth gives a huge list of various Ramayanas in his preface like Adbhuta and Ananda. He states, ‘interesting aspects of the above works have been incorporated in this book.’ He also gives a huge list of regional Ramayanas like that of Krittivasa and Balaramdas. He says, ‘The reader is likely to find some elements inspired by these monumental works in this book.’ But none of the unique elements of these literary works are incorporated in his work except a few which are listed below.

1. His strong influence of Bhavabhuti’s Uttara Rama charita is revealed in his first few essays. He takes from Kalidasa too while describing Valmiki’s rage regarding Rama’s spurning of Sita (p (page no): 16) and Dasharatha’s white hair’s suggestion to relinquish the throne (p:208). He takes from Bhasa’s Abhisheka Nataka, Rama’s wish for Dasharatha’s continuation as the ruler (p:208).

Description of Sita’s separation from Rama as the consequence of her past mistake of separating the parrot-couple in her childhood (p: 112) is from Padma Purana. Gautama’s circumambulation of a cow to win Ahalya’s hand found in Godavari Mahatmya of Brahma Purana is narrated (p:72&107).

2. Incorporation of Kamban in a few places like - Ayodhya, Chitrakuta, and Ganga’s descriptions, Sita-Rama-meeting before marriage, Dasharatha’s desire to make Rama the next king and not a deputy king as found in Valmiki, and Guha’s extol of Bharata to be thousand times greater than Rama.

3. His Janaka and Vishvamitra’s arrival to Chitrakuta is from Tulasidas.

4. Few stories like that of Valmiki’s previous life as Harit who was once a hermit getting involved in dacoity in due course of time and of Shankukarna, the sources of which are unknown to me.

Moreover, he also claims in an interview in a Tamil channel named ‘Peshu Tamizha peshu’ (5.28) (June 24,2024) that he takes from 125 + books in his work from various languages and this is of its first kind to his knowledge.

In general, Shri Dushyanth’s work is the combination of three: Valmiki, various Purana stories unrelated or less related to Ramayana, and his own imagination which he calls in his preface as his creative originality helped him dovetail certain loose ends.

A Few Examples of His Own Imagination and Thoughts

Shri Dushyanth starts his work with Sita’s abandonment with which he himself appears unconvinced. In his own words, ‘Sita…felt indebted to Rama for being the wish-yielding Kalpaka tree but was unaware that he was, in reality, the tree with sharp sword-like leaves, called asipatra (p:13).’ Bharata murmured to him, ‘This will remain a blot on Rama’s rule... (p:12).’ ‘…there was no justification for the treatment Rama had meted out to her…(p:16).

In the context of Dasharatha’s Ashvamedha, Valmiki asks Narada, “Isn’t it barbaric to sacrifice a horse?” After this Narada gives an explanation. Then it is stated, “Valmiki appeared unconvinced by the explanation.” (p:33).

Valmiki’s usage of the word barbaric has no equivalent word in Sanskrit. The words like savageous and barbarous, and the ideas behind them are foreign to Sanskrit. Westerners used to call the tribals and nomads, as savages and barbarous in a derogative way. If Valmiki had asked this question to Narada, what Sanskrit word he would have used for ‘barbarous’ which is a Western word?

In Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana, Valmiki repents after cursing the hunter, ‘I shouldn’t have uttered such words of hate.’ This is not found in Valmiki’s Ramayana (p:22).

‘She (Lakshmi) was sent away from the Samudra when Agastya drank its waters, hurt when Bhrugu kicked Vishnu’s chest and indeed left homeless when Atri plucked the lotuses, her favourite abode, for his daily rituals. I quipped that the houses in Ayodhya were always open to her (p:29).’

‘Dasharatha was known to make promises in a hurry and then to repent at leisure (p:42).’ Is this statement of Shri Dushyanth correct? Dasharatha did it in the epic twice in the contexts of Vishvamitra and Kaikeyi. Is it right to generalise this characteristic to Dasharatha?

In Shri Dushyanth’s imagination, Valmiki remarked, ‘How selfish of the devas to dispatch paramatma to ask dakshina?’ (p:57).

In the context of narrating Parashurama’s story, Shri Dushyanth says, ‘The Parashu broke Ganesha’s left tusk…He (Jamadagni) wanted the world to call his son Parashurama, henceforth (p:116).’ I don’t know from which Purana this story is taken. Or is it an imagination of Shri Dushyanth? The epithet Parashurama is not found in the earlier texts like Ramayana, Mahabharata and even Bhagavata. They call him as Bhargava or Rama. This epithet is a later development.

In the context of Sita’s marriage, Shri Dushyanth describes, ‘…the sapphires of Lanka and the pearls from Dravida be used for studding the golden Shibika meant for Sita (p:124).’

In the context of Vasishta’s narration of Savitri’s story in Savitri-vrata after the marriage of Sita and Urmila, Shri Dushyanth describes: The purohita said,’...when she attained puberty, her father solicited the permission of the brahmanas to find her a suitable match. Savitri, who had returned from an odyssey, revealed her love interest to Ashvapati.’ Urmila mumbled, ‘Wish our father had also given us this privilege.’ The girls giggled while the purohita continued (p:158).

Shri Dushyanth describes the love quarrel of Lakshmana and Shatrughna based on Bharata: He….said, ‘Vasishta wishes to narrate the life-history of Bharata and we must be his audience. Hasten to his Ashrama.’

‘Bharata, we know you well. Why your life history to us?’ asked Lakshmana with a straight face. ‘You do not know Bharata as well as I do. Maybe Vasishta wants you to know him better?’ Quipped Shatrughna (p:162).

There is a general trend among Pauranikas to elevate Ramayana’s Janaka by identifying him with Upanishad’s Janaka. In the same way, Shri Dhushyanth elevates Ashvapati of Kekaya kingdom identifying him with Upanishad’s Ashvapati. In his own words: ‘Yudhajit recounted the session where the sons of Upamanyu….had arrived at Rajagruha, the rajadhani of Kekaya. They had wanted to understand Vaishvanara…..Ashvapati of Kekaya laid on the discussion table the various connotations of the word ‘Vaisvhanara’ such as the digestive fire, the elemental fire, the fire murti……, the Jivatma and the Paramatma (p:171-172).’

Shri Dushyanth gives a vital role for Urmila in his work. ‘Fetch those earrings studded with diamonds, and those armlets laced in ruby stones,’ said Urmila to a maid. ‘Why do you ask for all of this?’ asked Sita in amazement. ‘Dasharatha has commanded that you should be decked well’ replied Urmila (265).

With tears rolling down her cheeks, Urmila said, ‘While he is in the forests, he will think of me. I will also be lost in his thoughts…I know he will cherish serving both of you. He has told me on multiple occasions that he sees you both as his parents. Why should I stop him from enjoying what he loves the most?’ (p:268). This is heart-touching.

‘…Dasharatha has asked you to be decked as always, even in the Dandaka forests. I suspect our father-in-law doesn’t want his reputation tarnished…Maybe he wants every passer-by to say “Dasharatha was always caring of his daughters-in-law”, said Urmila in a sarcastic tone (p:265).

She was pulled in a flash against the wall, and her mouth was quickly covered by a hand. In shock, her eyes didn’t blink when a voice said, ‘Stay quiet. The situation is grim. I can’t leave my brother’s apartment without knowing his further course of action.’ Urmila removed Lakshmana’s hand in a flash, disapproving of his uncouth behaviour. But equally worried for Sita, she too stood outside the apartment wanting to know what had transpired within the royal court (p:251).

Shri Dushyanth’s Valmiki narrates the crow-story getting additional information from Sita also who stayed in his Ashrama (p:306). ‘She innocently asked if Rama’s act rendered all the crows single-eyed. I laughed saying that all cows have two eyes, but to overcome the hindrance of their beaks impeding their vision, they only employ one eye to spot their target (p:309).’

Valmiki says that the people of Ayodhya burnt the tent materials when they continued their journey from Shringaverapura. It is a good culture to clean and pack after the stay in a particular place. We take that Valmiki describes this culture.

But Shri Dushyanth sees differently. ‘Vasishta, who knew that Ayodhya was bereft of its defending men, thought that she could be an easy target for enemies. He did not want to leave any trace of their stay at Shringaverapura which otherwise could tempt the rival rajyas. He ordered that the tent materials be burnt, which in itself also achieved an established practice of praying for the dear ones to be back in their native land (p:340).

‘What is that?’ asked Kausalya pointing at the wound on Sita’s bosom. Sita narrated the incident of how the crow had assaulted her…(p:357).

Shri Dushyanth’s Vasishta said, ‘With Dasharatha dead, Rama refusing to return, and you, refusing to be anointed king, only she can lead the praja now.’ Bharata wondered if it was Sita to whom Vasishta was referring, while Sita and her mothers-in-law were perplexed, wondering if Rama had a mistress, whom he had never spoken about (p:371).

Janaka told Sita, ‘….if you were pitted against his rajya, he will only choose the latter as he believes he is foremost wedded to his rajya…..he dons two hats: the hat of your husband, and that of Ayodhya’s well-wisher (p:373).’

Shri Dushyanth gives explanation for why Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna serve Rama’s sandals: ‘For looked down upon her as mere footwear at some point, the servants of Narayana must have done prayashitta this day with avataras of Ananta, Panchajanya and Sudarshana serving her religiously (p:374).’

Vishvamitra….said, ‘Vasishta does know the greatness of Paduka, but there are only two people who know her the best.’ Bharadvaja pleaded to Vishvamitra to reveal the names. Vishvamitra said, ‘Atri Maharshi, and I. Only either of us or our descendants can extol her distinction (p:374).’

Some Important Elements of Valmiki Which Shri Dushyanth Misses

Aside from what he adds, he misses some important elements found in Valmiki.

E.g. Though the people rejoice in the king’s decision to coronate his son in Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana (p:205), he misses a statement of Dasharatha found in Valmiki’s Ramayana. Dasharatha says, ’I have well thought a lot about it. I hope that it is befitting. Can you give your consent? What do you feel? What should I do? If my thought is right, please sanction this. Though this is my wish, you may think of alternatives too, as divergent thoughts of moderators are better (2.2.15-16).’ These words of Dasharatha show him as highly democratic.

I am surprised that Rama’s explanation of the transitory nature of the world featured with profound wisdom found in Valmiki’s Ramayana (2.105) which many of the Valmiki Ramayana scholars wish to quote in their narration of Ramayana, which even Buddha referred to in Tripitaka in his narration of Rama’s story is skipped by Shri Dushyanth. I don’t know why. This is not an insignificant place to be skipped.

These points are neither a fault nor a deviation from Valmiki. But when Shri Dushyanth dedicated 96 pages for many Puranic stories which are unrelated or less related to Valmiki like that of Brihaspati’s passion to his sister-in-law, I wonder why he has skipped such a significant wisdom found in Valmiki’s Ramayana?

Deviations From Valmiki

In Valmiki’s Ramayana Sumitra is the last among the three queens. But in Shri Dushyant’s Ramayana, she is the second one while Kaikeyi is the last (198).

Dasharatha says in Valmiki Ramayana, ‘People will hate me for my son’s renouncement like they hate a drunkard Brahmin (2.12.79).’ But in Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana, Dasharatha laments, ‘our praja castigates a brahmana for consuming Varuni….They will subject me to a similar treatment when I deviate from the practice of performing Pattabhisheka for the eldest son (p:230).

While renouncing an innocent son is a fault, not coronating the eldest son is breaking the custom. Here Valmiki talks on fault while Shri Dushyanth talks on custom.

When Sumantra comes to see Rama in the morning, Rama is described by Valmiki as getting seated. But Shri Dushyanth describes Rama resting his head on Sita’s lap (p:236). This does not seem appropriate as Rama does not lie, that too on Sita’s lap in morning hours which are meant for Vedic rituals.

Garuda is described as the son of Kashyapa by Shri Dushyanth (p:239). This may be right according to some other Puranas. However, according to Valmiki, Garuda is Arishtanemi’s son.

Errors

Shri Dushyant gives a reference from Taittiriya Aranyaka in his footnotes when he narrates Vaivasvata’s desire to build a perfect province (p:28). The Mantra to which he refers does not talk about any province at all. Neither does it talk about Vaivasvata’s desire to build a province.

The reference given from Brihadaranyaka Upanishad for treating the eldest brother to be one’s father (p:41) is wrong. Treating the eldest brother as one’s father is again described as Shruti’s injunction (p:162). I don’t know what Shruti offers this injunction.

‘The devas wanted a Senapati, an army chief to conquer Tataka (p:49).’ Taraka is wrongly mentioned as Tataka here. The same mistake is committed again on page number 64.

Hiranyakashipu’s attendants are called as Rakshasas (p:150). They according to Puranas are not Rakshasas; but Asuras. Asuras and Rakshasas are not one. Those who are familiar with Puranas and Itihasas know this very well.

‘Shiva bent his bow called the Pinaki……’(p:180). Shiva’s bow is Pinaka and not Pinaki. Shiva is called as Pinaki as he holds the bow Pinaka. Here the bow is wrongly called as Pinaki.

Sadhana in Sanskrit is always a neutral gender. But it comes in Shri Dushyanth’s book as Sadhanaa (E.g. p:195) in feminine gender which is grammatically incorrect. But in Hindi, it can come like this. The word Rani is quite often used. In Sanskrit or Tamil, this word is not found to denote queen. But this is not wrong if it is a Hindi usage. While I appreciate Shri Dushyanth’s attempts to retain many Sanskrit words in his book, he could have paid attention to these non-Sanskrit words as well.

Shri Dushyanth says that Sita sees Ganga for the first time in Shrigaverapura (p:281). This is wrong. Sita had already seen Ganga which is on the way from Mithila to Ayodhya.

Shri Dushyanth’s Kausalya quotes from Apastamba and Bodhayana (304). Since Bodhayana talks about Vishnu sahasranama and the Gita and since Ashvalayana who predates Apastamba talks about Mahabharata, these texts are post-Mahabharata works, but Ramayana is pre-Mahabharata one. Such an anachronism can be avoided.

Careful Narration Required

Shri Dushyanth’s Sita and Rama resolve to be celibate in the forest for 14 years (p:253). This is wrong because both of them had many love sports in the forest and expressed the peak of romantic passions both in their togetherness and separation. This is found mostly in all Ramayanas including that of Valmiki. Based on the word ‘Brahmacharini’ of Valmiki’s Sita here, Shri Dushyanth develops this. Absolute celibacy is not the only meaning of the word ‘Brahmacharya’ in all contexts about which Shri Dushyanth himself knows.

Seeing the amount of love sports and romantic passions in their forest life, we feel that it is wrong to take the word ‘Brahmacharini’ for absolute celibacy. Shri Periyavacchan pillai in his commentary named ‘Thanishloki’ says, that Sita has more free time, solitude and nature in the forest to express more romantic passions to Rama than in city life. Rishis and Munis are not Sannyasins. They had their own families. Rama adopted only their way of life. He did not adopt Sannyasa featured with absolute celibacy.

Dr S.L. Bhairappa in his book ‘Uttarakanda’ finds fault with Rama for being a recluse in his exile, with the least concern for checking on his wife and her comforts. He describes Rama to be a celibate in all 14 years in exile, with the least passion towards Sita. Devdutt Pattnaik too has a tint of the same in his book, ‘Sita, an illustrated retelling of the Ramayana’.

Shri Dushyanth talks on Shanta (p:197), the alleged elder sister of Rama, whom Puranas say, Dasharatha gave as an adopted child to Romapada. This story is not found in Valmiki’s Ramayana. Devdutt takes this as gender discrimination of Dasharatha. Making his daughter an adopted child, Dasharatha longs for a male child. These kinds of stories which are found in Puranas can be disassociated from Valmiki.

Shri Dushyanth’s Rama says, ‘Each one interprets the dharma as per their convenience (p:251).’ We should be very careful in dealing with Dharma. In my view we should not make such words to come from the lips of Rama. This is because the new age writers such as Devdutt Pattnaik wants to show Dharma in the same way and wish to disassociate the qualities like good or bad, heroism and villainism from the epic-characters like Rama and Ravana. Below given is a passage of Devdutt Pattnaik ‘Sita, an illustrated retelling of the Ramyana’ (p:117) (Penguin books, 2013).

‘Sometimes sages joined them and told them stories, full of heroes, villains, victims and martyrs. Sita enjoyed the tales but realized how each tale contained a measuring scale that converted one into a hero and another into a victim. All measuring scales are human delusions that make humans feel good about themselves. In nature, there is no victim and villain, just predator and prey, those who seek food and those who become food.’

Based on this he further builds his retelling of Ramayana.

Significance of Shapatha

पुरा भ्रात: पिता न: स मातरं ते समुद्वहन् । मातामहे समाश्रौषीद्राज्यशुल्कमनुत्तमम् ।।

The literal meaning of this verse: Rama said to Bharata, “Long ago our father made our maternal grandfather to hear ‘the best Rajya-shulka’ wedding your mother (2.107.3).”

I guess ‘oblige’ is the tone of ‘made to listen.’ Rajya-shulka literally means kingdom-fee/charge/price. Therefore the above verse can be translated as “Long ago our father obliged our maternal grandfather ‘the best kingdom-fee’ wedding your mother.” What does Rama mean by kingdom fee? We may guess it to be offering the kingdom to Kaikeyi’s expectant son.

By this, we may guess, that Dasharatha might have told Kaikeyi’s father that he would offer kingdom to Kaikeyi’s expectant son if he married her. Among 3000 verses found in Ayodhya Kanda of Valmiki’s Ramayana, this is the only verse where we can guess this information. Just based on this speculation some scholars articulated and wrote several things. Having this as a main subject matter E.V.R made a character assassination of Rama.

Here is the summary of what E.V.R. said: Rama who was very much aware of this, never resisted Dasharatha to crown him, since he wished to usurp the kingdom from Bharata, though rightly kingdom belongs to Bharata. Thus, Rama is a cheat. The virtues of Rama described in the first two chapters are sheer enaction to usurp the kingdom. This is the conclusion of E.V.R.

Shri Dushyanth pens a long essay (p:197-200) based on this Rajya-shulka. Assuming that Dasharatha is obliged to offer the kingdom to the expectant child, Shri Dushyanth justifies Dasharatha by saying, ‘promises made on five occasions can be circumvented if the need arises is what I have heard many rishis opine. In that list of five occasions, one is the promise made for a vivaha (marriage) to happen (p:199).’

I don’t think this answer is sufficient. First of all, we need to know whether Dasharatha’s word to Kaikeyi’s father is a Shapatha or not. This cannot be a shapatha, as, if it is a shapatha, Dasharatha will not break that for sure. It is not of his character. Truth is of two kinds- Shapatha and non-Shapatha.

One says, “I shall come to Mumbai tomorrow to attend a meeting.” But on the next day, he could not go there due to some vital reason, say, a severe headache. This is not wrong if it is not going to affect anybody. But even this kind of lie should not be told unless there is a vital reason.

Let us see a few examples of this from Ramayana itself. While Rakshasis ask Sita the details about Hanuman, she says clearly that she does not know him at all (5.42.10.). Though this is a lie, this safeguards her and Hanuman. Therefore this lie is not wrong. While Rama leaves Ayodhya, Dasharatha asks Sumantra to stop the chariot. But Rama impels Sumantra to drive further, saying, that Sumantra can manage if he shall be asked later by the King for the reason of Sumantra’s disobedience towards the King’s command, by telling that the King’s command was not audible (2.40.47.). Though Rama asks Sumantra to lie in this context, this lie is not wrong, because, if in this way thing is not managed, either Rama’s journey to the woods will be extremely delayed or the King might get upset with Sumantra.

At the time of Kaikeyi’s marriage, let us assume that Dasharatha told Kaikeyi’s father that his successor to the kingdom would be Kaikeyi’s son. While he said that, he had no offspring from his first wife at all. But later his first wife gave birth to Rama, who is the eldest among the four and who is the most lovable prince to the subjects. Therefore, ignoring his own words spoken to his father-in-law, the king arranges for the coronation ceremony of Rama, which is knowingly approved by Rama too.

Rama approves it though he knows his father’s words to his father-in-law. This is because he prioritizes the ideal governance that he is going to provide, over his father’s words to his father-in-law. Neither the king’s decision nor Rama’s approval is wrong because both give more importance to the ideal kingship and subjects’ wishes than the words spoken by the king to his father-in-law. Moreover, Bharata also is not going to get hurt; nay; he shall be the happiest person, if Rama is the ruler.

All these suggest that an ordinary lie is permitted in the context of safeguarding Dharma.

Kaikeyi and Manthara know this thoroughly. (They know that the king shall never consider ignoring his words to his father-in-law as wrong). That is why when they plan to exile Rama from the Kingdom, they never plan to raise the issue of the king’s words to his father-in-law. They make a new plan altogether of getting an oath from the King.

Shri Dushyanth says that it is known only to Dasharatha and Ashvapati. This need not be right. Then how does Rama talk about it? There is always a theological answer to all these kinds of questions. ‘Rama is omniscient. Therefore, he knows.’ But nowhere in the whole epic, he tells something which he is not informed. Therefore, if Rama knows it means Kaikeyi and Manthara too know. But they also know that this is not anyway going to help them.

If somebody has taken any Shapatha to do something, one should not fail to do it at any cost. The value of Shapatha is revealed throughout the second book. The Shapatha for which only two were witnesses, the Shapatha on being broken would affect nobody and by which nobody was going to misunderstand Rama, the Shapatha which was not even taken by Rama, was considered by Rama as extremely significant for which he sacrificed the whole of his Kingdom. This is stunning.

On those days all the business transactions were based on Shapatha. Orally one used to make a Shapatha or take an oath to repay the debt on a particular date. He certainly did so fearing breaking the oath. Even now all the court transactions are based on this oath. How can a convict be proven a convict? How can a judge trust a convict to be a convict? How shall a judge not misunderstand an innocent to be a convict? Is it just through the conversations of lawyers in the court?

No. It alone cannot help. A lawyer who supports a convict may talk effectively while another lawyer who supports an innocent may talk inefficiently. This may lead only to the judge’s misunderstanding of a convict to be an innocent and an innocent to be a convict. Is it not?

Can the video clips, photography, audio voice recording and his signature which reveal the blunders of a convict be the pieces of evidence? No. Video clips and photography can be explained as camera tricks. Voice recording can be described as mimicry. A signature can be called forgery. Even if all of these are available, they all can be dismissed in some way or the other. How can one judge if they are not available?

Here the only three pieces of evidence are the hearts of the convict, victim and witness. If they fear to contradict their heart through their words in the court then certainly it becomes easier to find the faulty one. If they are comfortable in contradicting their hearts in their words then the case becomes complex and the guilty cannot be found at all. Anybody who is answerable in the court takes this oath in the court: “Whatever I say on this Dais is true.” After taking this oath even if he tries to break the oath his conscience shall prick him severely. Therefore, he shall remain truthful without breaking the oath.

In a society where Shapatha-breaking becomes common, consistent, fashionable and conventional, nobody bothers to break Shapatha. There the conscience becomes dull and becomes hardly visible. Then the case in the court becomes complex which may lead to punishing the innocents and releasing the guilty. If the guilty ones are released consistently in this way, then there will be a severe infiltration in society. The faulty ones shall start to co-exist with the normal persons of the society.

Further, seeing the unpunished faulty ones, normal people also may start to commit blunders for their selfish needs. In this way, the whole society shall get corrupted, filled with cheats in all sectors of the society. That society shall perish in which the people are proud to be untruthful and where the people feel cheating is smart. That corporate shall perish when the promotions are given to the so-called smart ones. That state shall commit social suicide in a literal sense which considers truth as outdated and lying as a fashion.

Rama considers truth as the highest value to sustain society (2.109.13.). He also considers it as an obligation, especially of the government and royals as they are the exemplars of the society (2.109.9.). He realizes that if he breaks his father’s oath, people shall start to follow it which in turn can lead to chaos. Rama calls truth as God (2.109.13.). If Rama had broken the oath and had become the king, all the subjects would be happy temporarily including his mothers and brothers.

But in the long run, this shall provide the way to the loss of truthfulness in the state which can corrupt the whole state. Keeping the oath in this context may make his brothers, mothers, subjects, father and his wife suffer for a time being. But in the long run, it sets the right model for society leading to a truthful and therefore corruption-less society. It is logical if we say that keeping Shapatha or truth leads to social development.

Rama’s Meat Eating

“After hunting four great animals, boar, Rishya, Prushata and Maharuru, taking the pure part quickly with hunger, Rama and Lakshmana went to the tree in the right time to dwell there (Valmiki’s Ramayana, 2.52.102).”

This small verse has a long interpretation by Shri Dushyanth which is as follows: after a Muhurta, he (Lakshmana) returned with bodies of a wild boar, deer of the rishya, prashta and maharuru species on his shoulders smeared with their blood. Muttering a certain mantra, he slowly peeled the animal skins and let the blood ooze out. The deer hides were washed in Ganga waters and spread on grass for dying. He carefully extracted the vapa portion, a peritoneal membrane guarding the abdomen, from these animals. He ignited a fire and offered the vapa to the devas. As a small portion of the vapa go consumed in the fire, he took the remaining burnt portions and placed them on a leaf. He washed the blood off the pieces of meat, skewered them on a Medhya stick and cooked them on the fire before placing them on the leaf. Lakshmana respectfully offered them to bhutas, those guardians of the forests, and to pitrus, the representatives of one’s forefathers.

Rama and Sita came to the spot where Lakshmana was conducting the sacrifices to the devas, the pitrus and the bhutas. They too joined Lakshmana in the prayers but were visibly taken aback at the carcass in one corner and the dried animal skins. Lakshmana placed the charred vapa, and the cooked Medhya on a leaf and presented it to the dampati. Rama and Sita looked at each other confused, when Lakshmana said, ‘These are prasada offerings, bereft of any papas. It would not be contradictory to the commitment you have made to Dasharatha.’ The dampati found Lakshmana’s justification corroborated by a shruti injunction and thus consumed the prasada with reverence (p:291).

What is the necessity of such a detailed explanation? In Shri Dushyanth’s book, the author is introduced as, ‘He has broken several stereotypes when it comes to Harikatha.’ It seems the above passage is one of the breaking processes of Harikatha stereotypes.

Generally, there are ample references in Ramayana for Rama’s consumption of only fruits and roots in his forest life. Only in very few occasions, did his meat-eating is indicated. I don’t take them seriously as they are uncommon in different recensions. It is a convention among scholars to doubt the uncommon verses in different recensions as interpolation. Even Govindaraja does it in the context of chapters 59-63 in Kishkindhakanda.

In chapters 102 and 103 of Ayodhya Kanda, Rama offers the pulp of the Ingudi tree mixed with the pulp of plums as a libation to his dead father Dasharatha. Valmiki says he offers it because it is his food in the forest. Valmiki also says one has to offer one’s own eatable to his gods and manes. Seeing Rama’s offering, Kausalya cries understanding it to be Rama’s food in the forest. These chapters confirm what Rama ate in the forest. It does not have meat. Shri Dushyanth skipped this in his book.

Rama says to Kausalya, ‘I shall abstain from consuming meat like a Muni (2.20.29).’ Shri Dushyanth interprets this verse as: “as I will be living the life of a tapasvi, I shall abstain from consuming meat unless any Kriya that I perform demands consumption (p:244).

न मांसं राघवो भुङ्क्ते न चापि मधु सेवते। वन्यं सुविहितं नित्यं भक्तमश्नाति पञ्चमम्।

Hanuman says, Rama neither eats meat nor he drinks alcohol. He eats only well-prescribed Vanyam (fruits and roots) every day (5.36.41.). Shri Dushyanth shows the cause of Rama’s rejection of meat as Sita’s separation as Rabri Devi’s fasting when Lallu was imprisoned. The statement सुविहितं (well-prescribed) here proves that this is wrong. Some ask if Rama never drinks, why does Hanuman particularly mention Rama’s non-consumption of alcohol? Some soldiers and rulers consume alcohol. Seeing Rama’s pious life where he avoids meat and alcohol, Hanuman admires it as a great virtue.

Sectarian Thoughts

In Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana, the popular story of Shiva’s birth from Brahma and his cry is narrated (p:103) in the context of the description of Shiva’s bow. This is not found in Ramayana. Shri Dushyanth describes Bhrigu’s curse of Shiva: ‘His followers shall henceforth digress from the path laid down in the Shastras. His followers shall prefer Varuni and flesh. They shall become heretics, professing only the wrong doctrines (p:105).’

Valmiki asked, ‘...And what cult did the followers of Shiva carve?’ Narada said, ‘...Gautama realized that Shandilya and his group had played a prank on him. The enraged Rishi said, ‘You all shall be banished forever from the sphere of Vaidika existence and your practices shall be despised by its adherents.’ ….Gradually, practices such as holding skulls, smearing bodies with ashes of burnt corpses and consuming Varuni by these transformed rishis were frowned upon by those who adhered to vaidika doctrines. Shiva….wanted to honor the curses of Bhrugu and Gautama- two Vaidika purists- and created this mohashastra as the solution (p:107).

Scientific?

Shri Dushyant gives the year, month, day and date of the birth of Rama and his brothers (p:38), of Sita’s marriage (p:137), of Dasharatha’s death (p:305) and of sandals’ coronation (p:375). He acknowledges Dr. Jayashree Saranathan for this in his preface. According to him, Ramayana happened before 7000 years. This has led to the controversy. Some Pauranika scholars (narrators of Puranas) stood for their belief that Ramayana happened before several lakhs of years ago. Shri Dushyanth responded in an interview that he wants to be researchful in dating Ramayana so that today’s youngsters who can get convinced only through scientific system would be convinced with the historicity of Ramayana and history textbooks can have Ramayana. (Minutes: 59.29 & 1.01.35) (Guru channel, July 14, 2024),

If one wants to follow science strictly one can have Rama’s dating as well before 1000 BCE which B.B. Lal, the director general of the archaeological survey of India, suggests in his book ‘Rama, his historicity, Mandir and Setu, Evidence of literature, archaeology and other sciences (p:30) (Aryan books international, New Delhi, 2008) based on archaeological search in the sites where Ramayana happened. Shri Dushyant’s footnotes are based mainly on archaeo-astronomy and astrology which don’t enjoy the high status of archaeology regarding authenticity in today’s scientific community.

As a reconciliation of Puranic belief and archaeological findings, a pious believer may say: that sciences like archaeology have their own limitations. E.g. Ancient History Encyclopedia (2014) talks about the scholars in the research world contesting the 'Three Age System' and questioning its very framework and premise. This system's limitations such as its narrowed geographical domain, mostly operating only within the European continent, and its tapered technological orientation tempt one to push this factor only to play an ancillary role in this context, especially, when overriding evidences exist through other methods.

Criticism of the Three Age System is summarized in Wikipedia. The age of homo sapiens is recently upgraded from 200,000 to 300, 000 based on some findings. These kinds of limitations suggest that the sciences like archaeology do not get advanced to the level of finding the upper limits of the date of Ramayana. This can be a pious believer’s view.

Shri Dushyanth is neither scientific nor Pauranic in dating the epic. His is the third stand i.e. the stand of archaeo-astronomy. Even here Nilesh Oak states that Ramayana predates 13000 years. P.V. Vartak states Ramayana happened before 10000 years. Pushkar Bhatnagar views that Ramayana happened before 7000 years. Shri Dushyanth stands for the third one.

Shri Dushyanth observes that through dating Ramayana can be brought into historical textbooks. Neither Shri Dushyanth’s date is accepted by the renowned scientific community nor a thing is made scientific or researchful to be brought into history textbooks. E.g. Aryan invasion is a perfect myth totally unscientific and irrational that still exists in history textbooks. This only reveals the unfortunate fact that the history is in victor’s hands.

Shri Dushyant seems to attempt to remove some supernatural elements in the epic. E.g. when a celestial being appeared in front of Dasharatha from his ritual fire, Shri Dushyant says, ‘Into the Vedika walked an extraordinary person…..’ (p:35). In this context he does not talk about a person appearing from fire, but just walking that too on a Vedika (stage or platform).

Trishanku’s ascendance to heaven is described as Trishanku’s climbing the hill towards Amaravati. Indra…hurtled him upside down…..Trishanku tumbled down the hill…..Kaushika…..exclaimed, ‘Wait there….’ Trishanku was held mid-hill (p:84).

Valmiki’s Ramayana describes Vinata as the mother of birds and Kadru as the mother of snakes. But Shri Dushyanth narrates, ‘the sisters used to regularly visit the caves with the remnants of the Yajna conducted by Kashyapa. Kadru used to feed the snakes while Vinata, who was averse to snakes, used to feed the birds (p:239).’

Puranas narrate that the moon was born to the couple Anasuya and Atri. Shri Dushyanth says that a boy whose face was as brilliant as Chandra was born (p:359).

In an interview in a Tamil channel named ‘Guru channel’, (minutes: 44.22) (July 14, 2024), Shri Dushyanth says that Ravana used to travel through land to cross the sea as a natural bridge already existed before Rama’s arrival. Thus he changes Ravana’s air-voyage into a land travel.

Though Shri Dushyanth removes supernatural elements in these contexts, he adds many more supernatural elements in several other contexts and also adds various Purana stories that are more supernatural than what we see in Valmiki’s Ramayana. In fact, this reminds me of Vimalasuri, the author of Paumacharia, a Jain Ramayana. Vimalasuri not only removes several supernatural elements in Valmiki’s Ramayana in his own narration but also condemns Valmiki for incorporating supernatural elements. But he adds more supernatural elements in his epic which are more intense than what we find in Valmiki.

In his interview to Shri Rangaraj Pandey in Guru channel (minutes: 56.18) (July 14, 2024), he says, ‘Ramayana had happened twice: 1. Before 7000 years and 2. Also before several lakhs of years.’ He says that he is telling this based on a popular saying ‘history repeats itself.’ Is this not an extremely unscientific or irrational statement from a strict scientific perspective?

Shri Dushyanth is modern; but not progressive. He is modern because he gives the modern examples to gladden the teens. But he is not progressive as he has unscientific and sectarian thoughts as we see above. On seeing him we can understand that not all modern are progressive and not all progressive are modern.

Vaishnava Tint

Valmiki describes Rama’s worship of Vishnu in the form of offering oblations to the ritual fire. This is interpreted by the Vaishnavite commentators as Rama’s worship of Ranganatha as his lineage-deity. Shri Dushyanth describes this worship in many other places repeatedly.

Shri Dushyanth describes Shiva’s accomplishments only as the effect of Vishnu’s blessings. This is the style of Vaishnava texts: E.g. Halahala did not harm Shiva as he performed achamana by repeating the names of Achyuta, Ananta and Govinda (p:134). He (Shiva) meditated on Narayana, whose grace he sought in the arrow… Shiva smiled and discharged the arrow, it travelled like the streak of a lightning, piercing the asuras (p:181).

Despite his Vaishnava spirit, sometimes he takes Shaivite's story also and narrates it in a polished way. E.g. ‘…Narayana is said to have asked Shiva for the Chakra, in his inimitable manner. The three-eyed Shiva wholeheartedly gave away the Chakra to Narayana, whom he used to fondly refer to as the “lotus-petal eyed” one.

When Lakshmana surrenders to Sita and Rama, Suyajna advices Lakshmana to recite ‘Dvaya Mantra’ in Shri Dushyant’s Ramayana (p:271), which Shri Vaishnavites take at the time of surrendering to the Lord.

Bharata asked, ‘Why is this pair of Rama padukas relevant to us now?’ Bharadvaja said, ‘It has been our tradition to seek the blessings of the tried Padukas of acharyas, that are worthy of aradhana. Rama is your brother, your father and from now on, your acharya too. Rama’s absence should not be felt by you, as you will have the Padukas in his place (p:371-372).’

Age of Sita

‘Bharata …. and Shatrughna … spent the next twelve years at Rajagruha (p:186)’ says Shri Dushyanth. This is derived from Aranya Kanda of Valmiki’s Ramayana (47.4) which says Sita stayed in Ayodhya for 12 years after her marriage. उषित्वा द्वादश समा इक्ष्वाकूनां निवेशने। In the same context Sita’s age is given as 18 when she started to forest (47.10). These are the verses from southern and northern recensions.

From this, the age of Sita when she got married is taken as six by southern and northern commentators. Shri Dushyanth is also in the same view and he expresses it in several of his talks. They also take another verse from Balakanda which says that Rama’s age is below 16 when he went with Vishvamitra. This is one view.

There is another view too. The critical edition of Valmiki’s Ramayana (BORI) which was published after researching 2000 manuscripts states that Sita stayed in Ayodhya for a year after her marriage. Mainly eastern recension of Valmiki’s Ramayana states in the same way. संवत्सरं चाध्युषिता राघवस्य निवेशने। ततः संवत्सरादूर्ध्वं सममन्यत मे पतिम्॥ If this is correct then Sita’s age of marriage is 17.

व्रतैश्च ब्रह्मचर्यैश्च गुरुभिश्चोपकर्शित: । भोगकाले महत्कृच्छ्रं पुनरेव प्रपत्स्यते ।।

“Rama was tormented by the austerities and disciplines in Gurukula. Now at the time in which life has to be enjoyed, he is going to get affected again,” cries Dasharatha when Rama is about to be exiled (2.12.85.). Dasharatha can tell this only Rama wrapped up his Gurukula education recently.

रामस्तु सीतया सार्द्धं विजहार बहूनृतून् । Rama enjoyed with Sita many Ritus (1.77.26.). This comes immediately after Sita’s marriage. Ritu means 16 days after menstruation. Also, it was believed at the time of Ramayana, that it is a sin to skip the union in Ritus after marriage before the birth of the first baby.

ऋतुस्नातां सतीं भार्यामृतुकालानुरोधिनीम् । अतिवर्तेत दुष्टात्मा यस्यार्योऽनुमते गत: ।। ।। (2.75.51.).

Joy in Ritu is not possible with a toddler around.

Ramayana says Sita got married at an age convenient to have a union with her husband (2.118.34.). पतिसंयोगसुलभं वयः । These verses are found even in southern and northern recensions. They definitely suggest Sita’s marriage after the age of 17.

Shushruta says, ‘if a woman aged below 16 is impregnated by a man aged below 25, the child will get troubled in the womb. Even if the child is born, either it will not live long or it may live with weak (diseased) senses.’ (Shusruta samhita, Shaarirasthana. 10.54.).

Sita’s age at the time of her wedding is consistent with Shushruta Samhita.

One may say, ‘union could have happened after 17. But Sita’s wedding must be at the age of six.’ It cannot be because skipping union in Ritus after the wedding before the birth of the first baby was considered a sin at the time of Ramayana (2.75.51.). If the wedding occurred when Sita was six, the couple would have skipped many Ritus before the age of 17 – a sinful act. If they had union immediately after Sita’s puberty, the couple transgresses the injunction found in Shushruta Samhita. So, the age of having a union as per Shushruta should be the age of the wedding in Ramayana’s period.

In Draupadi’s svayamvara, we do not see Draupadi as a six-year-old child. We see her as a paragon of beauty in her teens.

कन्दर्पबाणाभिनिपीडितांगाः कृष्णागतैस्ते हृदयैर्नरेन्द्राः।

रंगावतीर्णा द्रुपदात्मजार्थं द्वेष्यान्हि चक्रुः सुहृदोपि तत्र॥ (Mahabharata, 1.178.5.)

तेषां हि द्रौपदीं दृष्ट्वा सर्वेषाममितौजसाम्। संप्रमथ्येन्द्रियग्रामं प्रादुरासीन्मनोभवः ॥

(Mahabharata, 1.182.12.)

In the context of Svayamvara of Subhadra, she is also in her teen.

दृष्ट्वैव तामर्जुनस्य तामर्जुनस्य कन्दर्पः समजायत।

अलङ्कृतां सखीमध्ये भद्रां ददृशतुस्तदा॥

अथाब्रवीत्पुष्कराक्षः प्रहसन्निव भारत।

वनेचरस्य किमिदं कामेनालोड्यते मनः॥

(Mahabharata, 1.211.15,16.)

स समीक्ष्य महीपालः स्वां सुतां प्राप्तयौवनाम्। अपश्यदात्मनः कार्यं दमयन्त्याः स्वयंवरम्॥

Seeing Damayanti who attained her youthfulness, the king arranged for her Svayamvara (Mahabharata, 3.51.7.)

वैदर्भीं तु तथायुक्तां युवतीं प्रेक्ष्य वै पिता। मनसा चिन्तयामास कस्मै दद्यां सुतामिति॥

Seeing Vaidharbhi who attained her youthfulness her father contemplated, I should give her to whom? (Mahabharata, 3.94.27.).

यौवनस्थां तु तां दृष्ट्वा स्वां सुतां देवरूपिणीम्।

अयाच्यमानां च वरैः नृपतिर्दुःखितोभवत्॥

पुत्रि प्रदानकालस्ते न च कश्चिद् वृणोति माम्।

स्वयमन्विच्छ भर्तारं गुणैः सदृशमात्मनः ॥

Seeing his daughter (Savitri) in her youthfulness, the king became sad, as nobody begged her and said, O my daughter! This is the time of your marriage. None chooses you. May you search for your husband by yourself who can match you (Mahabharata, 3.277.31.).

Few verses of some scriptures that insist on pre-puberty marriage came later to Ramayana. In spite of their emergence after the birth of few verses that insist on pre-puberty-wedding, the later Ramayana poets retain Sita’s post-puberty wedding.

अपक्रान्ते बाल्ये तरुणिमनि चागन्तुमनसि

प्रयाते मुग्धत्वे चतुरिमणि चाश्लेषरसिके।

न केनापि स्पृष्टं यदिह वयसा मर्म परमं

तदेतत्पंचेषोर्जयति वपुरिन्दीवरदृशः॥

While her childhood is gone and the young age is planning to come while budding innocence has gone and the maturing skill delights to embrace her, her excellent core is not touched by any age (neither childhood nor young age). Thus, the form of this lotus-eyed girl triumphs being the paragon of Cupid (Jayadeva’s Prasanna Raghavam, 2.12.).

Almost all poets like Kamban, Madhava Kandali, Krittivas, Narahari and Tulsi had similar thoughts regarding Sita’s age during her wedding. None of these famous writers describe Sita as a six-year-old child at the time of her wedding.

Moreover, Bharata’s stay in Kekaya for 12 years also is absurd here. It can strengthen Manthara’s argument too as we find in Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana: ‘he had to leave Ayodhya. It is over ten years now…Did Dasharatha call him back from Kekaya, even once?’ (p:221). Bharata’s stay in the Kekaya kingdom for around a year found in the critical edition is more convincing.

Again, Shri Dushyanth by taking the side of Sita’s age as six while she got married, while a better option is there, he proves not progressive; though modern.

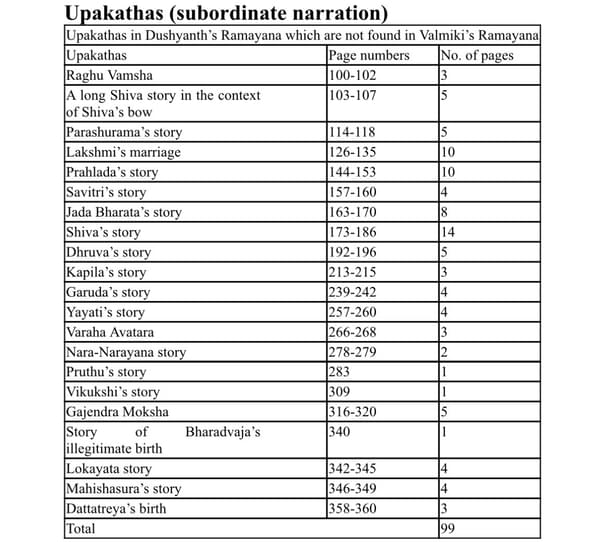

99 pages out of 378 are dedicated to Upakathas. The insertion of Upakathas in the profound main story of Rama is highly disturbing and mars the beautiful and profound flow of Rama’s story.

E.g. Bharata requested Vasishta to brief him about Bharadvaja’s birth. Vasishta happily agreed...When Mamata was pregnant, Brihaspati, Utathya’s younger brother, tried to force himself on her. She resisted Brihaspati’s sexual advances citing her pregnancy. Brihaspati felt insulted and cursed that the child in her womb would not see the world. As cursed, the little one was blind at birth... Again, when Utathya was away from his Ashrama, Brihaspati forced himself on Mamata. Fearing the state of her blind son, Mamata fell victim to his venereal pleasure. When the child was born, Utathya refused to accept the child, and Mamata spurned him too. Considered a burden by both Utathya and Brihaspati, he was called Bharadvaja (p:340).

When a profound story of Bharata’s devotion is going on what is the need of this story here? what message does the author want to convey through this story? What is the necessity of adding this story here?

Valmiki’s Ramayana has very rare Upakathas with Balakanda as exception where Upakathas occur in stoic situations. E.g. When Rama and Vishvamitra got seated in the bank of the river Ganga in a relaxed way, Vishvamitra narrates the story of Ganga. But in Shri Dushyant’s Ramayana, most of Upakathas occur in the middle of events filled with emotional highs and lows which appear disturbing.

When Rama offers everything to the poor getting ready to start his journey to the forest with Sita and Lakshmana, all of a sudden, Valmiki requests Narada to narrate Yayati’s story (since the whole book runs in the form of Valmiki-Narada-conversation). Narada in detail narrates Yayati’s story (p:257-260). When the whole assembly is mourning, when Dasharatha is in distress and while even Vasishta feels heavy-hearted with Sumantra and Siddhartha, Urmila requests Sita to narrate Varaha Avatara. Sita narrates it in detail (p:265-268).

Even allusions found in Valmiki are narrated in detail in Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana (E.g. Shibi’s & Alarka’s stories, p:229-230, Varuna’s story p:245). These stories can come in appendices. But they intersect with Rama’s story.

I think Shri Dushyanth wanted to bring comprehensively all Purana stories in one book. I don’t know why he used the Ramayana story for that. He could have written a separate book named ‘Summary of all Puranas’ or he could have written a separate book for Vishnu Purana, the best of all Puranas or Bhagavata, the essence of all Puranas.

Upakathas in Shri Dushyanth’s Ramayana which are not found in Valmiki’s Ramayana=99 pages.

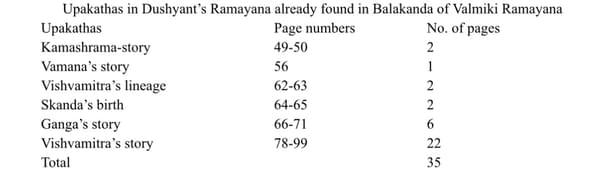

Upakathas in Dushyant’s Ramayana already found in Balakanda of Valmiki Ramayana=35 pages.

Total Upakathas: 99+35= 134

378 (Total number of pages of book)- 134 (Total number of pages of Upakathas)=244 (Total number of pages of the main narration i.e. Rama’s story).

Even in Balakanda Shri Dushyant not only retains all Upakathas found in Valmiki’s Ramayana but also adds much more elements taken from several Puranas in those Upakathas.

E.g. A long story of Vsihvamitra that runs for 15 chapters in Balakanda already paints him as rude. Shri Dushyanth adds many Purana stories further related to Vishvamitra. E.g. Vishvamitra impels a Rakshasa to go in disguise of Vasishta and order the king to bring human flesh, so that the real Vasishta would become angry and curse the king later. He impels a Rakshasa to kill Vasishta’s son. He tortures innocent Harishcandra and becomes responsible for the loss of his kingdom and his wife. By adding so many stories like these from later texts, Shri Dushyanth presents Vishvamitra as more cunning, cleverer and villainous.

Shri Dushyanth’s Bharata says, ‘I don’t know which Bharata, the son of Rishabhanatha or the son of Dushyantha, inspired Vasishta to name me as Bharata (p:333)’ Here Shri Dushyanth could have added Bharata, the author of Natya shastra too, whom the ‘great’ Bhavabhuti calls as contemporary of Valmiki.

Shri Dushyanth’s Vasishta narrates Rishabha’s story to Rama and his brothers. This story comes in the Puranas like Bhagavata in Hinduism. Rishabha is believed to be a great saint in Jainism also. A Jain picture of Rishabhanatha and his son Bahubali (found in Shravanabelagola, a Jain sacred spot) is given in the book here (p:165) which may sound to the readers that Jainism predates Valmiki’s Ramayana.

It is better always to avoid the stories which are unique to Puranas having no base in Valmiki’s Ramayana while writing the narration of Ramayana. This can lead to different kinds of anachronism. Due to the lack of clarity of knowledge regarding chronology, this can get utterly confusing. E.g. since Bhavishya Purana talks about Mohammad, Akbar, Humayun, Kabir, Ramanand, Jesus, Victoria and British conquerors we cannot bring the above characters in Ramayana.

Tomorrow someone may write Sai Baba Purana in Sanskrit and would ascribe its authorship to Veda Vyasa. By this, we cannot get fascinated and narrate, ‘Rama while staying in Panchavati visited Sai Baba’s shrine and paid homage to the great saint.’

Keerthivasan Ramachandran is an angel investor and mentor in the defence and tech startup ecosystem. He is deeply involved in various projects for Indian culture, philosophy, and history – especially related to Valmiki Ramayana studies for 25 years.