Culture

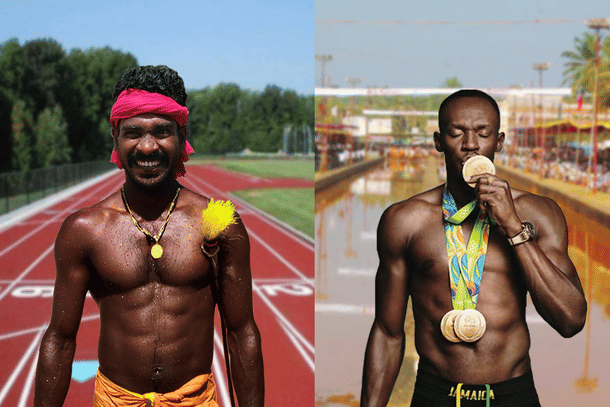

Kambala Champions Don’t Need Olympic Validation, They’re Champions Already

Harsha Bhat

Feb 17, 2020, 03:52 PM | Updated 03:52 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

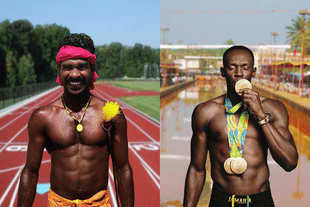

Kambala — a word that was until last week known only to the coast of Karnataka and a few elsewhere who were either vouching for or against the sport — has now gained international fame. Thanks to Sreenivas Gowda, whose record performance at the Aikala Kambala was mapped and reported as being ‘faster than that of Usain Bolt’.

The comparison did the magic and he turned into an overnight Internet sensation.

This led to him being invited by Minister of State for Youth Affairs and Sports Kiren Rijiju for trails by top Sports Authority of India (SAI) coaches.

The youngster is under immense pressure and has, as reported, said he doesn’t want to do the trials because running in the fields is not the same as a sprint on the track. But as we spoke to him on Sunday evening he was just back from another Kambala event and kept reiterating, "I only want to run Kambala".

The anxiety is momentary and with support and time (mainly for acclimatisation) he sure will be able to appear for the trials. Given his strides that we have observed in the past few seasons of Kambala, he sure has it in him to even qualify.

But if there is one thing his refrain should get us to think about is, why can we not make room for indigenous sports to be as prestigious and supported as the institutionalised ones? Like his speed, does the talent also have to be ‘mapped’ onto a few ‘recognised’ sports for it to be worthy of applause?

Like we wrote here, this is not the first time a runner has clocked these timings in Kambala. Even this evening, in the semi-finals another runner did clock in 0.01 seconds lesser than Seenu’s record, but he didn't make it to the finals, while Seenu won another three medals this evening.

Nor will anything change for him if he doesn't ‘qualify’ in the trials. Yes, it could be life-changing if he does qualify and then is mentored for larger goals as far as the games are concerned. But amidst all the hullabaloo what we are failing to acknowledge is that, if we make it just about this one runner, are we simply mistaking the finger for the moon.

This school dropout, construction worker’s 13.62 seconds to fame, and our sudden spurred activism of now wanting the system to intervene and ‘identify this sporting talent’ sums up all that is wrong with our way of handling our organic talent and potential.

It is Kambala which has made him a star today. Culture has done for him what the system failed to do. An indigenous practice pitched in to harness that which an institutional setup should have.

Is it not time then that we consider institutionalising support to these indigenous sports and practices? Every region of this country has sports and practices that are extracting excellence out of individuals but are forced to battle the odds of sustaining them as those practices don’t in most cases earn them their bread.

It would be ideal if the government could now steer action in this regard. Why not set up a centralised department of indigenous sport that will identify local sports that have been integral to the culture of every region, fund their pursuits, make room for employment opportunities for those excelling in those under the sports quota (Seenu dropped out of school)?

If India truly has to ‘rise and shine the Indic way’ then Indic sports need to be supported.

An entire ecosystem from bull keepers, to caretakers, to bull releasers, to runners was thrown out of gear when Kambala was banned for two seasons, thanks to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) wanting to tell us they know more about our animals than we do.

Protests were held across the coast but in the city of Mangaluru, strangely most youngsters who had joined the protests had only seen Kambala in pictures as most Kambalas had been discontinued.

Land mafia in some places, lack of funds to rear the bulls in most and the PETA’s torture and the legal hassles had led to all Kambalas within the city to wind up. That is when legal sanction was given to resume Kambala, and it was decided to recreate the experience for the city.

While traditional Kambalas are held in fields where a track is organically created, a group of youngsters decided to curate it in a large stretch of land. The intent found such resonance that from the land to the organisation of the race to the participation, Mangaluru Kambala found unimagined organic support. Thousands of people now turn up for the day-and-night event, which is in its third year now.

It is the likes of a Sreenivas who are keeping it going. But who will keep them going? When he trained six years ago at an academy there were 84 of them, of whom, he says, hardly a handful have continued running. Most of these runners are farm labourers, are involved in intense physical activity and hence do not require extra ‘training’ to stay fit. But the numbers are dwindling.

While a few decades ago the number was above 50, today it is less than 20. People from across communities, caste, religion ran the Kambala. Like the other 51-year-old who has been running for the last three decades, most of them barely make ends meet after they have spent their earnings on the bulls that they also rear.

But even then, many bull owners would want to participate in all races but don't as they cannot afford to take them to all the venues. It involves transportation, the labour who go with the bull, the feed for the bulls and the allowance for the caretakers, the payment for the runners and so much more.

The rising costs only add to their woes giving them fewer reasons to indulge in the ‘luxury of being who they are’.

Why then can we not provide:

- Recognition for our Indic sports by according them status on a par with other sports.

- Provide the required support in terms of employment in public sector institutions.

- Aadhaar-linked provision of monetary allowance and pension provision for those pursuing these Indic sports.

- Insurance and subsidised medical care for these sportsmen along with safety measures in the case of sports like Jallikattu.

- Subsidies for the upkeep of the buffaloes that can also be a part of a nationalised cattle ID system. Provisions like horse gram (that is to be fed twice a day) and oil (1 litre a day for the massage of one buffalo) are a huge cost for a farm labourer to bear and can be provided at the public distribution system outlets along with monthly ration.

- Exposure and support for the conduct of such practices as well as legal backing to fight non-stakeholders who take these practices to court.

- Include these sports in the current educational setup — make them part of the extracurricular activities.

- Encourage dialogue regarding ‘changes’ that can be brought in to adapt the sport for the changing times (but not kill it for lack of understanding) by setting up academies for training where applicable.

Given all the attention that the extraordinary feat has got to Kambala, it would only be apt that we initiate action in this regard and the ripple effect that it will have for all Indic indigenous sports will surely revive the glory of Indic sporting traditions.

If the rulers of the past could afford to patronise these folk practices, utilise the cultural capital and see value in the soft power, a democratic setup should be able to do all that more at a much larger scale, greater pace, and bearing a greater impact on the overall cultural psyche of the nation.

Also read:

1. Kambala’s ‘Usain Bolt’ Jockeys: Sprinting In Slush To Save A Cultural Tradition

2. Kambala: How Enthusiasts And Farmers Are Keeping Alive An Old Tradition

3. [Watch] Kambala: A Celebration Of Crop, Cattle, And Community Living

Harsha Bhat is an author, linguist, content strategist, and a compulsive chronicler of Bharat's civilisational heartbeat.