Culture

Navratri Notes: Guanyin, The Goddess Of Compassion

Aravindan Neelakandan

Oct 11, 2024, 06:43 PM | Updated Oct 18, 2024, 04:17 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

She is the Goddess of endless compassion. She is the Ocean of mercy. She cannot live in Heavenly peace if Her children need liberation. She comes to them. She comforts them. She is among them.

She is also the Goddess of wisdom. She holds Her hand in the sacred gesture of Gnosis. In the Southern Sea of far East, She stands holding the texts that symbolise Divine Knowledge.

She is Kwan Yin or Guanyin.

She is the Bodhisattva who came to be with the people as an eternal presence. She is Avalokiteswara who is in the tenth level – the level which leads to Buddhahood. But Avalokiteswara who could enter into Buddhahood would not, because He wants to always cast His eyes of compassion downward towards the people.

When Buddhism, as the great vehicle or Mahayana, went into China, Avalokiteswara was an indispensable part of Buddhism and Buddhist version of Vedic deities.

Buddhist text, Avalokitesvara-Guna-Karandavyuha belonging to 5th century CE, makes Avalokiteswara the Primal Man – or the Purusha from whom come the Vedic deities.

From his bodily pores all the worlds; from his eyes, the sun and the moon were born; from his forehead, Mahesvara (Shiva); from his heart, Narayana (Vishnu); from his shoulders, Brahma and the other deities; from his teeth, Sarasvati; from his mouth, Vayu; from his feet, the earth; and from his stomach, Varuna.

He was the personal deity, serving as a holistic and relatable bridge to Buddhahood for lay devotees.

But what should be remembered here is the close organic relation that Avalokiteswara has with Vedic Gods and worldview. Already the Vedic Purusha Sukta imagery becoming part of the syncretic and cosmic form of Avalokiteswara has been seen. Even more fundamental is his relation to Varuna the Vedic God. The imagery dates back to Harappan times.

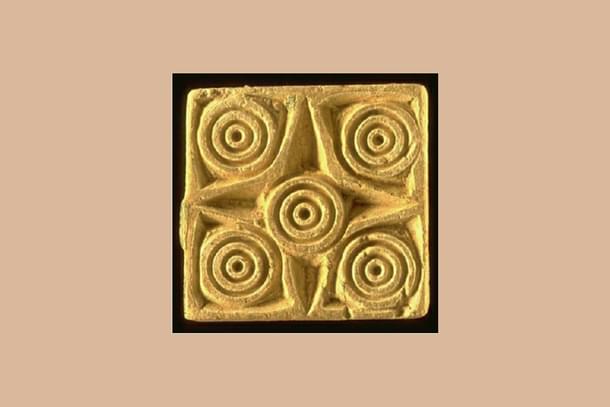

It is an enigmatic button seal that is now almost 5000 years old. It shows a star with a concentric circle in its middle and concentric circles around it. It is from Indus Valley Civilization.

Parveen Talpur is a an archaeologist and historian from the Lower Sindh region of Pakistan. In her book on Indus Seals published in 2017, she identifies this seal as the eye of Varuna.

She points out that this was the representation of the thousand eyes of Varuna. They are fish-eyed because they are unblinking. They always watch over the people, his children, from above. They are thousand eyes – an ancient way of saying infinite eyed. The same is the nature of Avalokiteshvara. 'He is also like Varuna thousand eyed'.

Thus the compassionate form of Buddha through which devotees can relate to Him, has its roots in the Vedic Universe.

How did Avalokiteshvara become the Goddess?

To understand this, one has to again look into the Vedic elements that are present in the core of Buddhism.

The nascent Buddhist religion ran the risk of becoming a patriarchal, cult-like movement. Like all religions, Buddhism also had anti-women strand in it. It was present in its earliest strands. Thus, the female body was regarded not only as negative but also as the opposite of the more spiritually and physically idealized male body of the Bodhisattva.

Buddhist scholar Reiko Ohnuma explains:

While the woman's body not only shares in but actually serves as a privileged emblem of the impurity, impermanence, and foulness of all ordinary human forms, the male bodhisattva's body is another matter altogether: like the perfectly controlled and decorous body of a good monk or the golden colored and irresistibly attractive body of the Buddha, the male bodhisattva's body falls into a Buddhist category of "ideal bodies" that seem to overcome the limitations of the ordinary human form and are exalted rather than degraded. The woman's body and the male bodhisattva's body thus stand at opposite ends of the ideological spectrum of Buddhist conceptions of the body.Woman, Bodhisattva, and Buddha, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion , Spring, 2001, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 63-83

In many Buddhist texts (as also in Smriti-related texts of Hinduism) we find the place of woman degraded. Even when Buddha teaches women, like the seven daughters of a Brahmin, and they became ready to become Bodhisattva, they had to abandon their female bodies and transform themselves into males.

Despite all these impediments how does Avalokiteshvara become a woman Goddess?

The answer again should be sought in the Vedic anchorage. Right from the Vedic texts to the higher Vedantic vision, Varuna the spiritual substratum of Avalokiteshvara, is a feminine Deity. Indologist specialising on Vedic literature Georges Dumézil points this feminine continuity of Varuna.

The Satapatha Brahmana declares Varuna is the womb" (yonir eva varunah). In Mahabharata, Purusha and Prakriti relation – a basic feature of Sankhya Darshana- was shown as the equivalent of Mitra and Varuna (Mitram Purushan Varunam Prakritim tatha). Dumézil explains:

In the other great Indian philosophic system, the Vedanta, the two antithetical components are Brahman and Maya, and they, too, are divided in accordance with the same system: on the one hand, the celestial projection-masculine-of the brahman (and remember that the old liturgical texts, when contrasting him with Varuna) say that ‘Mitra is the brahman’); on the other, the creative illusion (and Maya in the Veda is the great technique of the magician Varuna).George Dumezil, Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty, 1988, pp.178-9

Maya in Vedanta, for example, in Adi Sankara's Vivekachudamani, is also the Goddess and all Her attributes. She is Avyakta. She is Paramesa Shakti. She is Trigunatmika; She is Para; She is Maha-adbutha, She is Nirvachaneeya.

In Saiva Siddhanta also She is the Creative Shakti of Shiva - both to bind and liberate. The Divine Feminine in subsequent Hinduism has its roots not only in explicitly female deities but also in the feminine divine qualities of Vedic Deities like Varuna.

If the eye is an important cosmic divine sign of Varuna, all the Goddesses in Hindu tradition who also define the sacred geography of India, have the divine attributes of their eyes as their defining principles – Kamakshi, Visalkshi and Meenakshi.

Avalokiteshvara, with his 'ever-watchful thousand eyes,' transforming into the Goddess, likely stems from this deep connection to the feminine essence of the Vedic god Varuna.

Secondly there is the influence of Vak from the Vedic civilisation.

Vak, the daughter of Rishi Ambhrina became the perceiver of Vedic Mantra and when the Vak Sukta came through her, it also united the rishika with the Goddess Vak – a cosmic feminine principle.

She became the Goddess embodying and bonding with all divinities. She became the rashtri who would wield the bow and fight for Dharma against those who deny the Brahman.

Brahman is the uniting common and individualistic principle in all. Anyone who arrogates for himself special status, craves more resources and is greedy, anyone who hates others, is in principle the hater of Brahman. She battles them.

This Goddess becomes a Sattvic Goddess in Hindu thought. Goddess Durga-Bhavani are Her martial attributes. But in Buddhist tradition as revealed in Suvarnaprabha Sutra’, or the ‘Sutra of Golden Light’, extant in Chinese Buddhism, Saraswati is with both the attributes. She is a multi-armed Goddess who fights for Dharma.

Here, we see Buddhism accepting and preserving a Vedic Goddess while continuing Her development in a way faithful to Her Vedic form. In the case of Vak Ambhrini, we find a model where a human being transcends human limitations to become a divine manifestation. Vak, the Goddess, thus becomes a divine phenomenon, fully absorbing Vak the rishika.

In China this become an important model for Avalokiteshvara. The Vedic value system that a woman could become a mantra-drashta and become Divine Vak – was adopted by Buddhism. The Bodhisattva can be a female in female body itself. Avalokiteshvara could become a Goddess.

In China the legend of extraordinarily compassionate princess Miaoshan became the focal point of the Goddess tradition. She was persecuted by her own father because she wanted to become a nun. When she was violently attacked by his father who wanted her to get married and thus get him a son-in-law to rule the land, she refused.

During all the persecutions she was protected by the powers of Guanyin, the female Avalokiteshvara. Then the princess allows herself to be killed. At this point a tiger drags away her dead body. She goes to the nether world where she remains in meditation for nine years and becomes Guanyin – the Goddess of thousand eyes and thousand hands – a Vedic imagery starting from Varuna and transmitted through the Bodhisattva to the Chinese Goddess.

Many Goddess traditions throughout China, Japan and larger South East Asia, did not get suppressed but became rich and evolved further with the spread of Buddhism.

Imagine for a moment a Buddhism without the Vedic Divine Feminine in it. Buddhism that spread outside India was mostly immunised by its mother body of Vedic Divine Feminine against becoming susceptible to the trends of prophetism.

Unfortunately today, influenced by colonial discourse we see Buddhism either as a kind of Lutheran reform movement or a completely rebellious anti-Vedic religion. This model needs a lot of distortion and denial of basic facts of Buddhist and larger Vedic Hinduism to sustain itself.

One is the denial of the Divine Feminine. Either all Divine Feminine elements in Buddhism, including its Tantric dimensions, should be seen as 'cunning Brahminical corruptions'. Or they should be explained away as ancestral worship retained by Buddhism which again was cunningly appropriated by Brahminism. Both deny the spiritual vibrancy and empirical evidence as well as experienced reality of Divine Feminine.

That the removal of Divine Feminine from Buddhism can make it a destructive power can be seen in Sri Lanka. Dogmatic Buddhism, devoid of divine feminism, but married to ethnic nationalism can be an agent of human misery.

In a way, the modern anti-Hindu reconstruction of Buddhism in neo-Dalit circles is committing the same error.

So it is time we bring in into our understanding of the history of our religions and society the compassion of the Divine Feminine – Saraswati and Guanyin.

Also read:

1. Navratri notes: Nammu, the forgotten Serpent-Sea Goddess from Sumeria

2. Navratri notes: Inanna, the Goddess of Life and War

3. Navratri notes: Maat, the Goddess of Cosmic Order, Breath of Life, and Justice

4. Navratri notes: Artemis, The Goddess of Wild Life and Child Birth

5. Navratri notes: She flows like Ganga, Saraswati, and also like Oshun of the Yorubas of Africa

6. Navratri notes: Gaia—Ancient Mother Earth reawakens in science

7. Navratri notes: Asherah, the Hebrew Goddess and the Tree of Life

8. Navratri notes: Cows, Thrones, and Triune Goddesses of Egypt