Culture

The Unyielding Hindu Spirit of Kanyakumari: A Multi-Generational Saga of Resistance

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jul 13, 2025, 12:12 PM | Updated 01:49 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In the southernmost tip of the Indian subcontinent, Kanyakumari, a recent event in early 2025 served as a stark reminder of a conflict that has simmered for nearly two centuries.

During a sacred ritual of the Mandaikaadu Bhagavathy Amman temple, the head priest, who is traditionally seated atop an elephant for a ceremonial procession that is part of the rite, was compelled to dismount and walk.

To many observers, this was not a simple dispute over right of way but a deliberate and planned humiliation, and it was just one frame in a long and complex film depicting the plight and resilience, resistance and vulnerability of the Hindu community in Kanyakumari.

From the spiritual awakenings of the 19th century that challenged the colonial-evangelical nexus, the fierce political and educational battles of the 20th century, to the organised Hindu movements and the contemporary struggles against new, subtler forms of encroachment, the Hindu identity of Kanyakumari has been forged through continuous struggle.

Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of the Indian mainland, holds profound religious significance for the nation. It is a place where Purana, history, and sacred geography converge, creating a unique and powerful spiritual landscape.

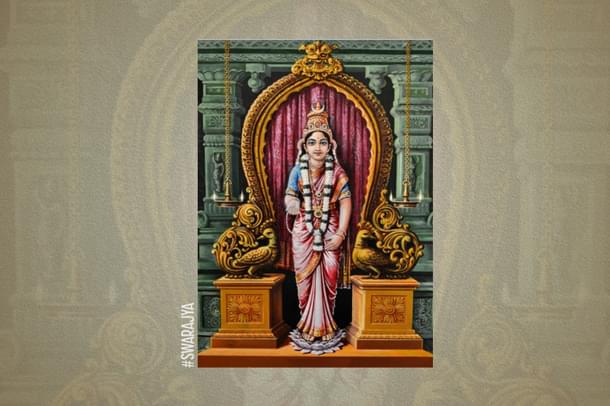

The town is named after the virgin goddess, Devi Kanya Kumari, an avatar of the Divine Mother Shakti, who is worshipped at the ancient Kumari Amman Temple.

This sacred site is revered as one of the 108 Shakti Peeths, the Divine Feminine nodal points. Goddess as the eternal virgin stands at the land's end. Standing with japa mala, She is immersed in tapas to win the hands of Siva who is the meditating Yogi of Yogis seated in Himalayas. Thus this small town is more than a scenic pilgrimage centre. It defines the spiritual essence of India.

Historically known as the 'granary of Travancore', the Kanyakumari district was part of that princely state until it was merged with Tamil Nadu in 1956.

Its history is dominated by the rule of powerful dynasties like the Cheras, Pandyas, and eventually the Venad rulers who established Travancore.

As early as the 16th Century, conversions had become a problem here. And as early as the 16th Century, the local communities were resisting it.

Support for the proselytisers came from unexpected quarters. In exchange of Portuguese protection that Catholic Jesuit Francis Xavier secured for the Venad kingdom against the Naicker invasion, the Travancore king not only granted him land to construct a place of worship but also the right to convert the coastal people. (It was Francis Xavier who had written to the king of Portugal to establish inquisition in their Indian territory of Goa).

The then Venad king, Bhutala Vira Udaya Marthanda Varma, warned Hindus of coastal provinces not to hinder the conversion activities. He made an edict warning 'the senior and junior Kangan... that they should not 'harass' the Christian converts who 'were exempted from paying the taxes due to the village community of the heathens...' (V.Nagam Aiya, The Travancore State Manual, Vol-I, 1906, p.296).

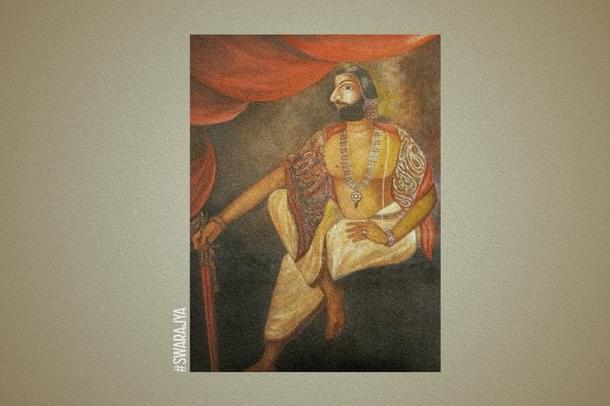

A pivotal figure in this history is King Marthanda Varma (1706-1758), who consolidated the kingdom, modernized its army, and dedicated the state to the deity Padmanabha Swamy.

It is within this 18th Century-landscape that the modern confrontation took deeper roots.

Converted Hindus in the army of Travancore were a great help for this king who had come to the throne after a set of conspiracies and ignoble murders. When groups of Brahmins opposed his ascent to the throne, his Diwan, himself a Brahmin, employed the battalions Christian converts to attack them because unconverted soldiers would not attack Brahmins. (P.Shungoonny Menon, A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times, Vol-1,Higginbothams, 1878, pp.153-4)

But this history would not prevent the Catholic Church two centuries later from falsely creating a martyr of 'official persecution'.

Divine Trustee to Colonial Puppet

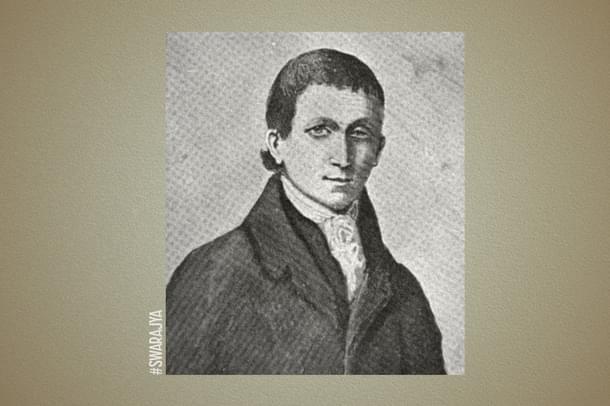

In 1816, the Prussian missionary, Ringeltaube, arrived in Kanyakumari; his presence precipitated by an unlikely encounter. His first convert and guide, a man named Maharasan, had embarked on a pilgrimage to Chidambaram, only to be swayed from his ancestral faith by Ringeltaube's preaching. Maharasan belonged to Sambavars, a Scheduled community in current times.

The missionary himself was notably discerning, reportedly rejecting prospective converts whom he suspected of seeking material advantage. He preferred 'genuine' conversion.

Ringeltaube's arrival, however, was not an isolated event but a precursor to a more methodical expansion of Protestant missions.

This was enabled by the shifting political landscape in the region, as the kingdom of Travancore solidified its status as a protectorate of the East India Company. With British authority effectively supplanting indigenous rule, the evangelical enterprise received robust governmental support. The local sovereign, who should have been ruling as 'Padmanabha Dasa'—a trustee for Lord Vishnu—was now ruling more as a puppet of the British.

As the British Reagent wielded actual control, the system created a symbiotic relationship with the Christian forces that facilitated the construction of missionary infrastructure.

This fusion of colonial administration and religious proselytising was starkly embodied in the actions of Colonel John Munro, the British Resident. Wielding considerable influence, Munro secured the appointment of Charles Mead, an ardent missionary, to a judicial position in Nagercoil.

The Travancore royal family, in turn, contributed lavishly to fortifying Mead's establishment. Whether this generosity stemmed from authentic conviction, political compulsion under the British, or an inextricable blend of both, remains a complex and unsettled question.

Consider this piece of information from the missionary records:

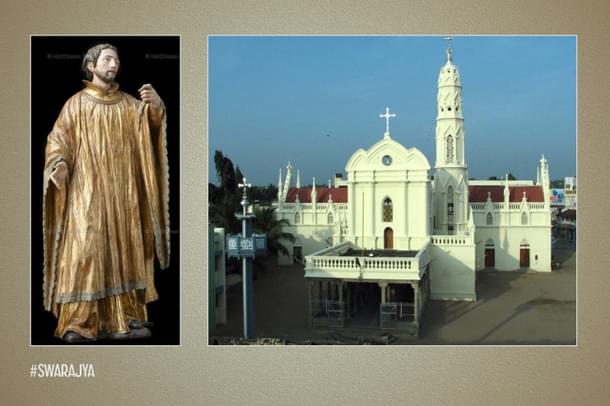

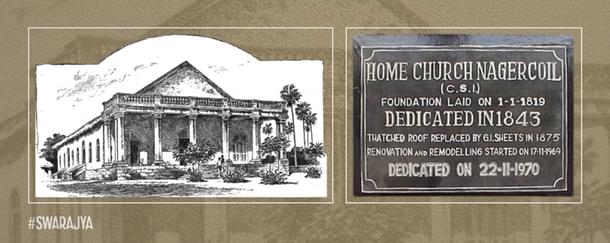

In this year (1818) the Ranee of Travancore gave a donation of Rs. 5000 to the mission (a sum of Rs. 20,000 was given at the same time to the Church Missionary Society in North Travancore), which Mr Mead added to the lands and put aside a portion towards the erection of the Nagercoil church.... On New Year's Day, 1819, was laid the foundation-stone of the great Nagercoil church. Mr Mead was able to employ a good deal of convict labour on the preparation of the massive stone foundation and plinth of the building, and during its erection, which extended over several years, large donations were received from the Maharajah of Tanjore, the Raja of Cochin, and also members of the royal house of Travancore. The erection of so large a building, 127 feet long by 66 wide, capable of seating two thousand people, exhibited a large amount of faith in the purposes of GodRev.I.H.Hacker. A Hundred Years in Travancore (1806-1906): London Missionary Society , H.R.Allen, 1908, p. 34

Despite the generosity showered on the mission from Travancore, a Hindu kingdom, Mead recorded the following in his diary:

West there is the Mohamedan mosque, in the East there stands a heathen Hindu temple, and on the highway in the midst I have commenced a House to the Living God. God grant that the other two should decrease and that this House should increase.C.M.Agur, Church History of Travancore, 1903, p.703

Mead had married thrice and fathered 15 children. His third marriage was to a teenage Indian girl when he was 60. This generated controversy - not because of the age difference and the possibility of coercion through authority, but because the girl belonged to a 'Paraiah community.'

His missionary colleague, C.Mault, wrote that 'the marriage of Mr.Mead to a young native woman of the Pariah caste, had filled the missionaries with surprise, disappointment and sorrow.'

Mead was given compulsory retirement but with pension, and he lived a comfortable life in Travancore till the end. One of the 'achievements' of Mead was that in 1866, four 'native' ministers were ordained by the Church he served.

The proliferation of Protestant missions soon inaugurated a competitive dynamic with the established Catholic presence, transforming the region into an arena for competing claims on the unconverted. While some rivalry involved luring adherents from each other's congregations, the vast Hindu population remained the principal prey for these competing predatory evangelisms.

The Catholics had already secured a significant foothold, having converted nearly the entire coastal population, a demographic that constitutes a formidable and strategic social base for the Church to this day. Consequently, the Protestant missions pivoted their focus inland, concentrating on the marginalised communities of the interior.

They found a particularly receptive audience among those groups that had been systematically disempowered and subjugated by the political intrigues and power struggles of the Travancore rulers from the 17th century onward.

With their position of authority secured by the colonial state, the missionary enterprise exerted immense pressure on the region's diverse Hindu spiritual streams. This new power dynamic led to both ideological and physical assaults on indigenous religious life.

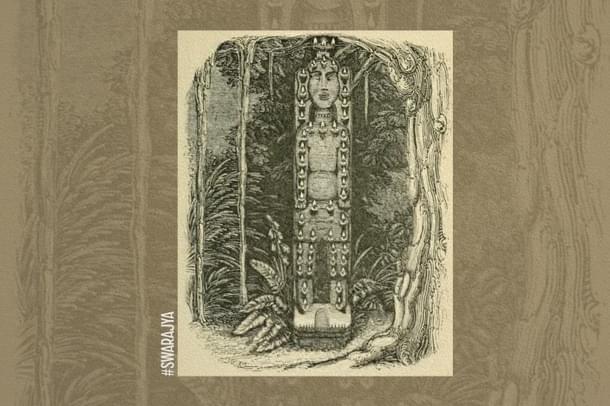

In some instances, the very temples where locals worshipped were destroyed by them upon conversion. Furthermore, sacred murtis were appropriated from these sites, a practice often framed by the evangelical instigators as an act of 'rescue'.

Removed from their consecrated contexts, these deities were then dispatched to missionary society museums in the West, where they were re-contextualized as ethnographic specimens and trophies of the evangelical campaign.

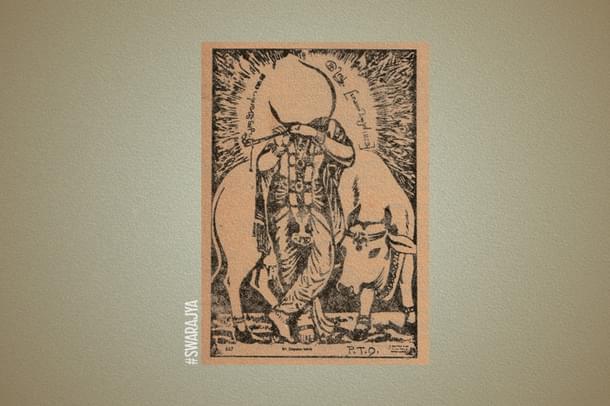

The image of Paramasattee (Heavenly Power), represented in the opposite engraving, was worshipped above thirty years ago at a village in Neyoor district.* It was committed to the flames by the people on their embracing Christianity, but was rescued by one of the missionaries. It was sent to England, and placed in the museum of the London Missionary Society, where it may now be seen.Rev. Samuel Mateer, The Land of Charity, John Snow & Co., 1871, p.203

Yet another evangelical account describes how a prime sacred tree in the forest was felled on the orders of a missionary. The description recorded 138 years before the release of the movie Avatar could well be the precursor to the iconic scene of the felling of the sacred tree in that movie:

In one of the mountains of Travancore grew a noble timber tree which our assistant missionary, Mr. Ashton, wished to secure for use in the erection of the large chapel at Neyoor. The trunk was so large that four men with outstretched arms could not compass it, and the branches were as thick as ordinary trees of that species. ... Even the native Government had refrained from cutting down this monarch of the forest for their public works.... The mountaineers firmly refused to assist in cutting down the tree, so that they had to bring Christian workmen from a considerable distance. At last the tree fell with a terrible crash, which echoed amongst the surrounding mountains, amidst the screams and cries of the heathen, who from that time seemed to listen more readily to the exhortations of the missionary.ibid., p.207

The British administration, using the local state as a proxy, imposed crippling economic burdens on the populace. New, punishing taxes were levied; a palm tree tax instituted in 1807 fetched the Company thousands of rupees. Furthermore, a cruel head tax was imposed on individuals aged 16 to 60 from communities like the Ezhavas, Channars, and Pulayas, while powerful landed communities, like the Nayars, Vellalas, Muslims, and Kanmalas were exempted. Under this tax, Rs 1,63,000 was collected annually.

But it was not as if the evangelists did not run into the conflict with the landed communities. In 1815, the then Travancore regent Col. Manroe made an announcement that the converted Shanars need not pay the tax levied on them by the state to be paid through physical labour at the temple. On the other hand, he lowered the market price of food grains while refusing to proportionately lower the taxes the paddy producers had to pay.

This created a strong anti-Christian feeling among the landed communities. The anti-Christian riots that followed were thus also conflicts where the landed communities vented out their frustration at the local converts.

This, in turn, fed the persecution literature of the missionaries. This also created an intra-community bond between the converted and non-converted among the marginalised communities. (S.Ramachandran and A.Ganesan, TholCiilaik Kalakam: Therintha Poikal, Theriyaatha Unmaikal [Tamil, Shoulder Cloth Riots: Known Falsehoods and Unknown Truths], South Indian Social History Research Institute 2011)

All this accelerated the conversions, particularly from the Hindu Nadar community, who were one of the most oppressed communities because of their political differences with the ruling elite in the foregone centuries. Rev. Hacker in his missionary history writes:

It was during the first year of Mr Mead's service that great numbers of Shanars were added to the church, as many as three thousand in one year. ... Ringeltaube refused to accept five thousand people of this caste when they came to him, as he plainly saw, from interested motives. It is doubtful if in Mr Mead's time their motives were more worthy. At any rate their accession is important, as this marks the beginning of the predominance of this class in the London Mission of South Travancore.Hacker, 1908, p.34

The engineered economic degradation had thus created a fertile ground for proselytising with the London Mission Society (LMS) exploiting the societal distress. The narrative however was one of liberation, casting the indigenous Dharma as a 'heathen religion of idolatry' designed for exploitation, with the colonial and evangelical masters positioned as saviours.

Dharmic Resistance: 'Parithranaya Sadhunam ...'

The trends at such a time pointed to Hinduism being gradually and steadily wiped out from the region, even though the rulers and the elite classes were staunch ritualistic Hindus.

It was at this time that the phenomenon of 'Iyya Vaikundar' emerged as a form of rooted, spiritual resistance to Christian proselytising.

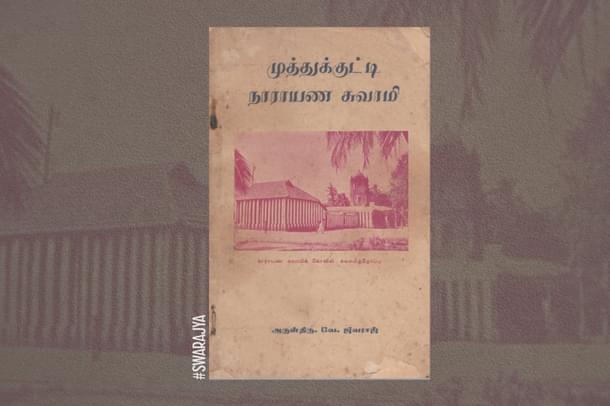

Muthukutty Swamy was born in 1809. He would become known to his followers as Iyya Vaikundar. Revered as an avatar of Narayana, he emerged as perhaps the first Hindu voice to systematically critique not only the foreign rulers but also the internal social stagnation they exploited.

He brilliantly articulated this dual threat by coining two powerful terms: ‘Ven-Neesan’ (the white-skinned evil-doers) for the British colonialists and ‘Kali Neesan’ for the local collaborators perpetuating the evils of the age (Kali Yuga).

Vaikundar’s genius lay in his ability to frame his socio-political resistance within a Puranic and Dharmic context. He associated the oppressive forces with the 'Asuric' characters from Hindu epics, such as Ravana and Duryodhana, making his critique of them accessible and resonant for the masses.

He correctly identified that the heavy taxation imposed by the British was the root cause of the socio-economic malaise, an analysis far more incisive than that of many university-educated Indologists of his time. He called his people the ‘Children of the eye,’ reviving an ancient honorific for the Channar community and weaving a motif of Puranic significance into his call for unity.

Vaikundar did not just preach; he built institutions. He established a temple at Osaravillai with dimensions mirroring the sacred Chidambaram temple, a symbolic act of reclaiming spiritual sovereignty. Here, he established a roof with 96 fittings, a profound representation of the ultimate reality (Chithasa) beyond the 96 principles of Saivaite Siddhanta, directly challenging the proselytizers whom he condemned as being ignorant of this all-pervading consciousness. His movement advocated for vegetarianism, cow protection, and fiercely condemned proselytization.

This potent movement effectively stopped the missionaries, who were having a "field day" among the Nadars of South Travancore, in their tracks. The colonial establishment, unnerved by his influence, reacted.

The notorious evangelist Robert Caldwell, who dismissed Vaikundar’s path as a "distorted heathenish imitation of Christianity," revealed the true reason for the state's intervention. He wrote in an 1844 report that Vaikundar began to "prophesy the overthrow of the Company’s government," which "led to the interference of the authorities and the prophet’s downfall". Another mission report confirmed that Vaikundar and his disciples began to "teach sedition" , leading the Collector to communicate with the Travancore Rajah, who subsequently had him arrested and imprisoned.

Despite missionary wishful thinking that the movement "gradually died away" after Vaikundar’s Mahasamadhi in 1851, it continued to thrive.

Reports from as late as 1871 lamented the increase of Iyyavazhi, calling the spiritual leader an 'impostor' who was one of the 'chief obstacles to the spread of the gospel'. The enduring legacy of the Iyyavazhi movement, with its distinctly Hindu rituals, vahanas (divine vehicles) like Garuda and Hanuman, and Puranic framework, stands as the foundational chapter of the holistic Hindu resistance in Kanyakumari. [You can read a comprehensive article on the movement in Swarajya here].

A Young Sanyasi visits

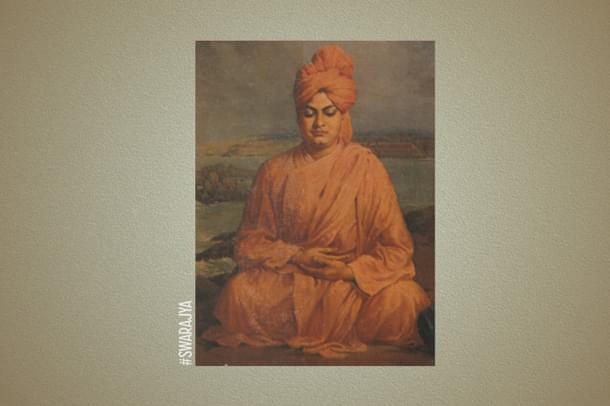

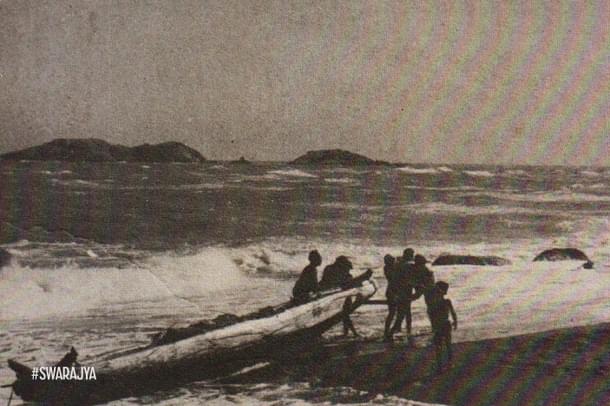

During the Christmas season of 1892, a young monk, after worshipping at the Kanyakumari temple, stood gazing intently at the offshore rocks, the last rocks of the Indian mainland. A Kanyakumari native, Sadasivam Pillai, noticed the monk's contemplative look and understood his desire to reach the rocks. Seeing the monk was about to swim, Pillai approached and asked in broken English if he could help, but the monk declined before plunging into the sea.

For three days and nights, amidst the roaring waves, blazing sun and eerie stars of Christmas night, the monk who would become known as Swami Vivekananda meditated. His meditation focused on the Goddess as Mother India and all her children suffering under colonialism from poverty, ill health, and illiteracy. There, he had a vision: to serve man as God.

At the same time, in the small mountains just a few kilometers from the coast, two other young monks, Chattampi Swami and Sri Narayana Guru, were also meditating. They too sought the spiritual upliftment of their people through the vision of non-dual oneness. These two figures would go on to revolutionise Travancore and become the architects of modern Kerala.

Hindu Resurgence takes Shape

Slowly Hindu awakening came into being. They started objecting to Christians erecting their places of propaganda which doubled as their place of worship near Hindu places of worship. In 1898 the Government of Travancore was forced to make regulation stating 'no place of public worship should be newly executed nor old existing building converted into public place of worship without the prior written permission of Travancore Government.'

In 1930 Catholic Church announced that Kanyakumari district, categorised as Kottar could be a separate diocese independent of Quilon. That led to a powerful consolidation of Catholics. Meanwhile Hindus were also becoming organised. Hindu Mission meetings were widely held across communities. In 1934 at Colachel the coastal town a meeting was conducted by Dewasom League for Hindu Propaganda which passed a resolution that the temple properties should not be leased out to non-Hindus.

In 1935 Hindu Nadar meeting was held in Kanyakumari district region by the Mission. Hindu Mission also worked strongly for the temple entry. In 1936 the famous temple entry proclamation was made. In 1937 Hindu Parathava Meeting was conducted by Kerala Hindu Mission at Kottar. The same year Hindu mission in Kanyakumari district reconverted twenty Christians.

Interestingly while Christian conversion logistics were provided by the Travancore State, the CID department of Travancore was closely monitoring and sending weekly intelligence reports on Hindu Sanghtan movement.

The effect of all these Hindu Sanghatan work in the district was visible. 1901-1911 the Christian numbers increased by 32 percent; 1911-1921 by 221.1 percent; 1921-31 by 32.7 percent. But between 1931 to 41 it was only 5 percent. (George Matthew, Social Action, Vol.33.No.4, 1983).

In 1940 an important event took place without attracting much attention. Swami Ambananda who was a student from Travancore studying in Madras, was transformed by a meeting with Swami Vivekananda in 1897 and took his Sanyaas from Holy Mother Sarada Devi.

He founded a simple hut of an Ashram in a two-cent land donated to him by an individual. It was then a forest area infested with snakes and scorpions with no electricity. It is quite an irony that while Christian missions could secure lavish money and land grants from Travancore's Dharma Rajya, the Hindu mission struggled and came up with individual donations from people of modest means.

The Continuing Struggle of Hindu Resistance

Even as the struggle for India's independence reached its zenith, a parallel movement for Hindu social reform and cultural preservation was gaining momentum in Kanyakumari district. It carried forward the vision of Iyya Vaikundar integrating it with the emerging national vision.

A key voice in this discourse was the magazine Thondan, founded and edited by Arumuga Navalar (not to be confused with the Arumuga Navalar of Eezham). The publication, though originating from a remote corner of the country, attracted contributions from the elite of the Tamil intellectual sphere, including poet Kavimani Desigavinayagam Pillai and trade unionist Thiru V. Kalyanasundaranar.

Thondan championed progressive causes such as temple entry for all Hindus, countering the arguments of orthodox sections, and even initiated a debate on whether temple revenues should be used for public education to counteract proselytization by other religions.

The magazine also served as a platform for nascent Hindutva ideology in Tamil Nadu, forcefully articulated by figures like Marai Thirunavukarasu, son of the progenitor of the pure Tamil movement, who argued against Dravidian separatist tendencies and emphasized a unified Hindu identity.

This early intellectual and social activism laid the groundwork for a more organized and assertive Hindu resistance in the subsequent decades, particularly in Kanyakumari. The groundwork by publications like Thondan, which mobilized public opinion and fostered a sense of Hindu unity, was crucial.

The magazine not only highlighted and appreciated temple entry proclamations but also reported on and actively countered on-the-ground proselytization efforts. This spirit of activism was later embodied by leaders who led spirited movements to protect Hindu rights and traditions in the region.

The concerns voiced in Thondan in 1947 about the dilapidated state of temples under government boards and the need for a 'national army of Hindustan' to protect Hindus, as advocated by leaders in the wake of the Noakhali riots, foreshadowed the formation of organizations like the Hindu Munnani in 1980. This later organization emerged as a street-level force to counter the perceived political and cultural aggression against Hindus, continuing the legacy of resistance that had been brewing for decades.

Torchbearers of Modern Hindu Resistance in Post-Independent India: Education, Politics, and Spiritual Revival

As India moved towards and beyond independence, the nature of the challenge evolved, and so did the leadership of the Hindu resistance. The fight shifted from opposing direct colonial rule to countering the deeply entrenched institutional power of missionary organizations in education and politics.

Christian missionaries unleashed various forms of attacks on Hindus. From imposed institutional dependence in the form of educational institutions to propaganda literature in the form of academic study of religions. In 1952 five years after Independence various Hindu community leaders came together for an important project. Every community and village temple would create a fund and share and they would launch a college.

Leaders of various Hindu communities Illangathu Velayudam Pillai Haindava Seva Sangha leader, Sivaramakrishna Iyer, S.Sundara Mudaliyar and many others came together and through their efforts the college materialised. Thirupananthal Adheenam, Desiyavinayaga Swami temple board which chiefly belonged to Chettiar community also provided needed land and basic infrastructure. This was a great vision and a milestone.

Haindava Seva Sangham leader Illangathu Velayudam Pillai and Thiru. S.D. Pandian Nadar another one patriotic missionary wanted to create a memorial for Swami Vivekananda on the birth centenary of the patriotic monk. In 1964 Thiru.S.D.Pandian Nadar founded Vivekananda College at Agastheeswaram near Kanyakumari. These two were the first educational institutions of Hindus in the district.

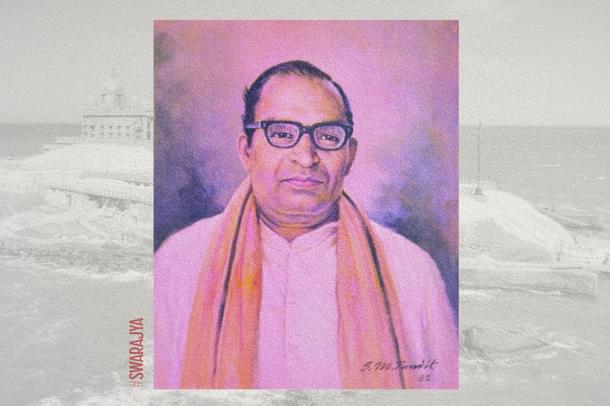

Three sons of the soil of Kanyakumari district from the 20th century stand out for their monumental contributions: Thanulinga Nadar, the political warrior; Swami Mathurananda, the spiritual architect; and Captain S.P. Kutty, the intellectual defender.

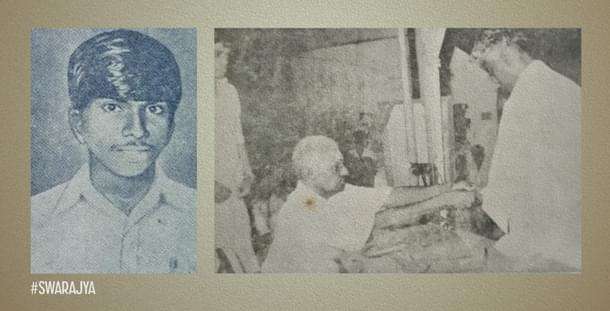

Thanulinga Nadar (1915-1988): A Gandhian with a Spine of Steel

The life journey of Thanulinga Nadar is a microcosm of the Hindu struggle in Kanyakumari. His activism was sparked by a personal family experience: his grandmother, Sitalakshmi, was outraged when a missionary school forced her grandchildren to remove their sacred marks and flowers, a policy she saw as religious persecution.

This incident was deeply personal for Sitalakshmi, who herself had been christened 'Kanni Mary' upon her father's conversion, only to return to her Hindu name, detesting the "psychological trauma the conversion was creating".

Galvanized into action, Thanulinga Nadar returned to his village and immediately addressed the root problem. He established the Sri Krishna Primary School to provide a non-persecutory educational alternative for Hindu children. The initiative was so successful that local missionary-run schools had to shut down due to a lack of students. He also began organizing community prayers and satsanghs, immunizing the local Hindu populace against proselytization through religious awareness.

Nadar’s sphere of influence expanded into the political arena. He was a key figure in the agitation to merge the Kanyakumari district with Tamil Nadu and became a lieutenant of the towering Congress leader K. Kamaraj. He skillfully crafted electoral strategies to counter the explicitly anti-Hindu campaigns run by Christian communal forces in alliance with the DMK. His influence proved decisive when he persuaded Kamaraj to ensure the Vivekananda Rock Memorial project was approved, overcoming opposition from within the government.

The 1982 Mandaikaddu riots marked a pivotal moment. In a peace meeting attended by then-Chief Minister M.G. Ramachandran (MGR), Nadar, who had been silent throughout, electrified the room with his commanding voice. He questioned the very premise of treating victims and perpetrators as equal sides, a query that left MGR "taken aback". The sheer force of his sincerity and honesty led the government commission to recommend a law banning proselytizing.

In his later years, Nadar grew closer to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), whom he admired as "Hindus with spine". He tirelessly toured villages where Hindus faced persecution, often being violently attacked himself, which only firmed his resolve.

In 1987, he undertook a fast unto death to demand the transfer of a headmaster who was distributing Bibles in a government school, an agitation that paralyzed the district and forced the government to concede. His life ended as he had wished, not in a sickbed, but on a stage addressing a conference for the centenary of RSS founder Dr. Hedgewar, his final words praising the man he saw as a divine leader.

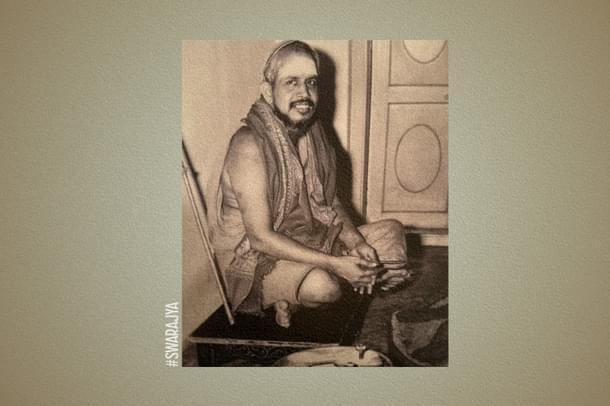

Swami Mathurananda (1922-1999): The Architect of a Spiritual Ecosystem

While Nadar fought on the political front, Swami Mathurananda of the Vellimalai Sri Vivekananda Ashram fought a quieter, but equally crucial, battle for the Hindu mind and soul.

As seen earlier its founder, Swami Ambananda took sanyaas from Holy Mother Sarada Devi. Swami Mathurananda, who took over in 1951, recognized the deep crisis of confidence within the Hindu community in the 1970s and 80s. Hindus, particularly the youth, were being systematically ridiculed for their traditions like wearing vibhuti and were often shamed into silence because they lacked knowledge of their own faith.

His response was the creation of the Samaya Vahuppu (spiritual classes), a sprawling network that ran through the towns and villages of the district. This was not a mere Sunday school. Swami Mathurananda personally crafted the textbooks for all levels, from primary to graduation. The curriculum was a rich exposition of Hindu thought, brilliantly weaving together the devotional Tamil literature of the Nayanmars and Azhwars with the profound wisdom of the Upanishads and the Gita, alongside stories of national patriots.

He built an entire intellectual ecosystem. He harnessed the wisdom of formidable scholars like Dr. Pa Arunachalam, a Saiva Siddhanta expert, and Sri N. Krishnamurthy of Vivekananda Kendra, an IIT MTech who walked to the remotest villages to teach the Gita. He popularized the sublime Tamil verse translation of the Bhagavad Gita by 'Tulsi' Ram, allowing children to memorize both the original Sanskrit and its lucid Tamil meaning. Graduates of this system, called Vidya Jothis, became a new generation of respected community leaders, qualified to teach, conduct pujas, and offer counseling, creating a self-sustaining movement.

Swami Mathurananda’s work provided the spiritual and intellectual backbone that allowed the Hindu community to move from a defensive crouch to a confident assertion of its identity. [Earlier Swarajya article on Swami Mathurananda is here]

Captain S.P. Kutty (d. 2024): The Warrior-Intellectual

Captain S.P. Kutty’s story represents the resistance of the modern, educated Hindu professional. An army engineer who served in the 1965 war, he returned home to find that predatory proselytizers had converted most of his family.

This personal tragedy, coupled with his experiences of caste discrimination—ironically, both in so-called 'upper-caste' quarters and in a missionary-run school—forged an unyielding resolve within him. When an evangelical relative dismissed the Bhagavad Gita as a "book which incites familial conflict," the young Kutty resolved to master it for himself and become a champion of Hindu intellectualism.

His resistance was primarily intellectual. He embarked on a self-study of Sanskrit and the Gita, eventually mastering its verses. He then took the battle to the streets, not with force, but with knowledge. He authored and distributed powerful pamphlets countering Christian propaganda, such as the insidious claim that Hindus were 'devil worshippers'. This armed ordinary Hindus with well-reasoned arguments, allowing them to defend their faith with newfound confidence.

His most ground-breaking work was in reclaiming history. He researched and wrote extensively on Iyya Vaikundar, repositioning him as an anti-colonial hero. The cover of his book was a historical indictment, depicting a soldier striking Vaikundar with a rifle butt—a weapon carried only by East India Company soldiers, not native troops. With this single, powerful image, he exposed the British hand behind the persecution of the Hindu leader.

Captain Kutty was also a gifted storyteller. His serialized novel in the Sangh Parivar magazine Vijaya Bharatam, inspired by the trauma of Partition, became a sensation and a powerful recruitment tool. In his later years, he penned a comprehensive commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, systematically dismantling the notion of a birth-based caste system and emphasizing its teachings of inherent equality. Today a great knowledge movement of Hindus in the district owes its presence chiefly to Captain Kutty. [Here is the Swarajya article on Captain Kutty.]

Women leaders of Hindu renaissance of the district deserve a very special mention. Ratnabhai S.P.Kutty the wife of S.P.Kutty, Dr. Lakshmikumari a botanist turned full time worker of Vivekananda Kendra who later on became its President and Om Prakash Yogini who defined the feminine spiritual aspirations of the district, they all worked in the field - going from village to village and worked tirelessly among the women and children.

Prequel to Mandaikaddu Riots:

Amidst relentless evangelical aggression, a burgeoning Hindu consolidation set the stage for a conflict that would erupt in both propaganda and physical confrontation. The hallowed rock where Swami Vivekananda had meditated in 1892 became the first battleground. When local Hindu leaders Velayutham Pillai and Pandian Nadar sought to build a memorial there, they were met with fierce opposition from Catholic fishermen, incited by a fanatical clergy.

With the Church enjoying the tactical support of the ruling Congress Party at both the state and central levels, local Hindus sought national support. The call reached the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and its leader, 'Guruji' M.S. Golwalkar, dispatched General Secretary Eknath Ranade with a singular mission: to ensure the memorial became a reality.

Ranade, however, envisioned more than just a stone monument; he sought a grand, living memorial befitting the Swami's legacy. With the blessings of His Holiness Swami Ranganathananda of the Sri Ramakrishna Mission and the monumental influence of Kanchi Sri Chandrasekarendra Saraswati, who helped persuade the Congress Chief Minister, Ranade undertook a Bhagirathic effort.

Even as political tides turned and the Dravidianist leader M. Karunanidhi took power, Ranade’s conviction was so profound that he won over the new establishment as well. By 1971, the magnificent rock memorial was inaugurated, a towering success and a symbol of triumph for the Hindus of the district.

Yet, the victory was but a brief respite.

Systematic Attacks on Hindu Temples

Frustrated Christian aggression became evident in the form of sporadic attacks on Hindu temples. The attacks were well designed. They would attract the least attention because these were small shrines. Usually there would at best be a 'third page small' report in a local newspaper and would never make it to national newspapers.

The village Hindus would not have the wherewithal to take their grievance to any national media. At the same time the local village Hindus would be thoroughly demoralised, thus facilitating predatory evangelism. After the riots the local Hindu activists submitted a compilation of these instances to the then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu M.G.Ramachandran. Here are a few of those incidents:

12-1-1980: Erumaivillai Sasta temple: Idols destroyed

8-1-1981 : Mayiladumparai Nagar shrine destroyed and a cross planted in the place of the Nagar idols.

13-01-1981: Paraiyadi Pathrakali Amman temple sacred vessels taken away by Christian mob days before temple festival and could be recovered with police force.

18-04-1981: Ganesa and 'Vel' removed from Murugankuntram

26-12-1981: Vazhikalampaadu village: three temples desecrated.

Occasionally country bombs would also be used in attacking village Hindu temples.

The year 1981 saw Christian aggression reach a well organised peak. Kanyakumari Congress Member of the Parliament Dennis participated in a fanatical Christian Unity March organised on the occasion of Christmas. A huge mob of Christians marched across the villages threatening Hindus, raising offensive slogans against Hinduism and at times attacking Hindu shrines and small Pandals made by Iyyappa devotees.

The same year a deeply offensive book on Iyya Vaikundar, published by a Protestant Christian Mission with the endorsement of the Concordia Seminary and the local Church of South India Bishop, ignited anguish among Hindus, particularly within the Nadar community. This was just one front in a renewed cultural war.

A deluge of pamphlets and street-corner sermons abused Hindu deities. This writer personally recalls a play glorifying St. Francis Xavier enacted in schools and churches —the very saint who called for the Goa Inquisition—as a hero exposing the 'tricks' of Brahmin priests. In this humiliating spectacle, the saint would drag the priest's wife from behind a Goddess idol to 'prove' the deity was a fraud. This wave of degradation was compounded by the erasure of identity, as Hindus watched helplessly while Christian-dominated localities systematically changed village names—as many as 127, according to a 1983 report in The Hindu.

Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamigal

Amidst a period of Hindu pushback against evangelical aggression, Sri Jayendra Saraswati of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham emerged as a pivotal spiritual leader, advocating for a constructive and unifying path. He called upon Hindus to fortify themselves not only socially but also through a deeper understanding of their spiritual heritage.

A true visionary, he championed the initiatives of Swami Mathurananda Maharaj and the Kanchi Peetham supported the project to publish textbooks on Hindu religious education. In his benedictory message Swamigal asked the Hindus to gather the children in every village in a public space like classroom or temple and start the religious instruction.

"Make them memorise the hymns. Tell them to study the stories. Create question-answer sessions and make them write. Make them memorise the Apta-Vakyas," his concern was genuine and his approach was practical and cost-effective.

To further this cause, Saraswati Swamigal launched the 'Iyyappa Jothi' Yatra, a procession carrying a sacred Iyyappa idol and religious literature through key Hindu villages. In a significant act of social reform, he visited the living areas and temples of the Scheduled Caste communities, encouraging so-called caste Hindus to serve them and bridge historical divides.

His approach was one of strategic pacification over confrontation. When an attempt was made to change the name of 'Ramanputhoor' to 'Carmel Nagar,' it provoked considerable agitation among local Hindus. When Sri Jayendra Saraswati visited the district this name change was one of the topics Hindu leaders brought out with much anger.

With his characteristic humour Saraswati Swamigal pacified them first, 'Is Rama not 'Karmegha Vannan' (the colour of dark clouds)? Therefore, consider Carmel as another name for Sri Rama.' Even as the tense faces relaxed, he guided the community leaders in pursuing successful legal and strategic countermeasures. Today Carmel Nagar is a small enclave within the larger Ramanputhoor, a practical outcome of his nuanced approach to leadership.

The dissemination of Hindu wisdom in the district however did not stop with this. Dr. Pa. Arunachalam a retired Tamizh professor from Malaysia University gathered a team and formed 'Arulneri Mantram'. They disseminated small pamphlets which explained with clarity and authenticity the core Hindu concepts.

Captain S.P.Kutty conducted Gita classes in every village for adult Hindus. 'Tulsi' a gifted poet translated Bhagavad Gita into Tamil verses and he translated 'Atma Sadakam' of Sri Narayana Guru into Tamizh vertses. They can be easily memorised. So now Hindus started knowing their religion and could recite both Sanskrit verses and their Tamizh meanings in verses. They could also explain Vedantic themes to Christians who discussed these aspects with them. The result was soon visible.

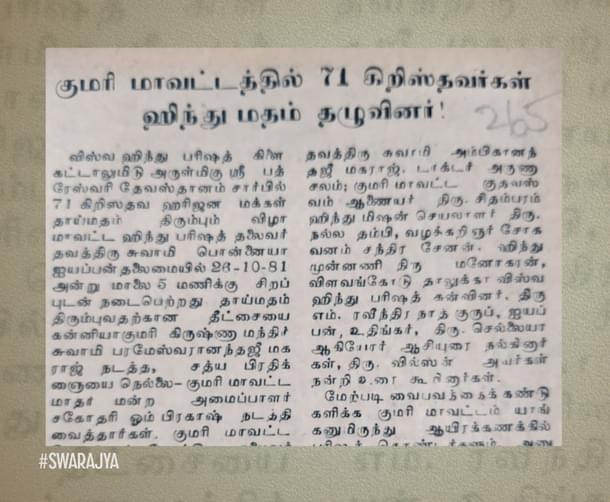

On 26-10-1981, 71 Christians reconverted to Hinduism. The 'Ghar Vapasi' was arranged by Hindu Endowment Board (Dewasom) of Kootallamoodu Pathreswari temple (a temple from a remote village.) Soon such sporadic mostly spontaneous 'home-coming' happened in the district thanks to the Hindu institutional and spiritual consolidation.

Organized Resistance and the Mandaikaddu Flashpoint

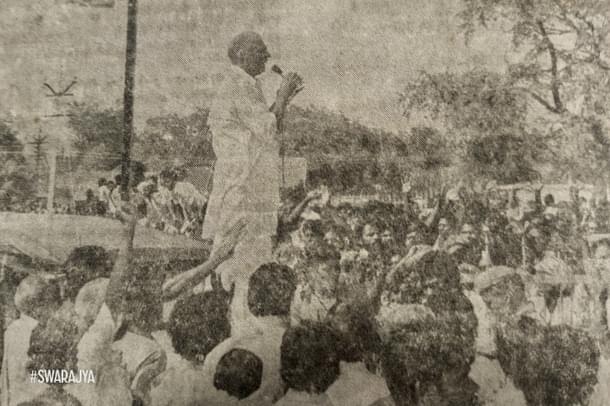

The individual and institutional efforts laid the groundwork for a more organized and assertive phase of Hindu resistance. In 1981 a mammoth Hindu Unity Conference was held at Nagercoil.

More than two lakh Hindus were estimated to have been present. Religious seers like Madurai Atheenam participated in the conference. Strong speeches were made against the conversion aggression. The district which had only seen large Christian conventions and rallies was shocked to see such a show of Hindu unity.

This rising Hindu assertion collided head-on with expansionist forces, culminating in the infamous Mandaikaddu riots. In 1981 there was an incident at Mandaikaadu during the festival. Christian evangelists started distributing pamphlets inside the Hindu festival venue. Local Hindus confiscated all the evangelical materials and burnt it.

The Mandaikaadu temple, known as the 'Sabarimala of women,' thus became the flashpoint. The violence was sparked when "Catholic zealots," encouraged by fanatical clergy, unleashed a torrent of humiliation and molestation on Hindu women taking their sacred sea baths. The subsequent tragedy, which involved police firing and loss of life. Later organised raids were conducted on Hindu villages in the nights. Many Hindus lost their houses and had to live as refugees in their own land.

The tragic irony is that missionary zeal of Christianity patronised by Hindu kings and queens of Travancore, the Dharma Rajya, would make the very Hindus orphaned refugees in that very land.

The government appointed the Justice Venugopal Commission to investigate. Justice Venugopal was a known staunch Dravidianist with a bias against the RSS, yet what he witnessed in Kanyakumari genuinely alarmed him. A careful reading of his report reveals that even he clearly identified 'the aggressive, expansionist, and intolerant behaviour of Christian radicals as the primary instigation for the riots'.

He was moved to tears by the testimony of the victims, particularly that of a 19-year-old unmarried girl who bravely recounted her humiliation at the hands of the mob. The judge found her testimony, and that of the other women, to be powerful and credible, concluding unequivocally that fishermen had 'caused trouble for them, humiliated them and molested them'.

Among the traditional Hindu leaders it was Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamigal who was the most prominent one to help Hindu refugees regain their livelihood.

Christian hate campaign was almost everywhere. Every Hindu festival was an opportunity to taunt them, as in the case of 'Headless Krishna' pictures sent by a Christian preacher to Bhaktas and priests of a village Krishna temple. The writing in Malayalam reads that 'head of Purushotama is Jesus'. This is typical of how evangelical hate campaign was carried out.

The Second Hindu Unity Conference

Hindu organisations decided to conduct a second Hindu Unity Conference in 1983. Fearing that this might become a regular annual feature the Christian Church was said to have given ultimatum to the ruling AIADMK to ban the conference. The date was on February 13, 1983. All due permissions from the district administration and police department had been obtained. Then all of a sudden Nagercoil woke up to discover that section 144 was imposed.

The decision backfired severely. Thanulinga Nadar the venerable old man defied 144. Within two hours two lakh Hindus assembled at the starting point of the rally. The assembled stood unarmed to face police brutality. The police opened fire on the unarmed crowd.

Official death toll was one. Many eye witnesses said a lot more should have been fatally injured. The doctors were said to have been threatened not to treat the wounded. In many hospitals police were present to stop the injured getting treated. Still a few brave Hindu doctors defied the police.

Late Dr. Ramachandran of Ramachandra Hospital had narrated the events to this writer. The anger of the people continued for weeks together. AIADMK became a hated party for Hindus of Kanyakumari district. It would take years for the party to regain the Hindu confidence in the district.

The riots and the aftermath though tragic, led to an unprecedented consolidation of Hindu unity and forged a formidable 'Hindu vote bank' (HVB) that transformed the region's politics. Hindu Munnani supported candidate for Legislative Assembly won Padmanabhapuram in 1984.

In other constituencies of the district the presence of Hindu Munnani supported candidates decided the winners. HVB formula was simple. Between a Hindu and a non-Hindu candidate, ensure the victory of Hindu candidate. Between two Hindu candidates ensure the victory of the candidate with a more Dharmic stand. Soon cutting across political parties HVB had to be taken into consideration.

But soon the woes of Hindu society returned. There were organisational splits, individual ego clashes and also lurking always in the shadows was the caste conscience. Today Kanyakumari district has quite a number of 'Hindutva' political parties. Some of them are fringe elements. But most of them were once staunch and strong field workers of the Sangh Parivar disillusioned for various reasons.

But this assertiveness came at a high price. Hindu Munnani and BJP leaders became prime targets for radical fanatics of proselytising religions. In 1983, Tirukovilur Sundaram was brutally attacked; in 1984, an assassination attempt on Rama Gopalan left him with a metal plate in his skull; in 1993 Kumari Balan a youth fulltime worker of the RSS died in the RSS office bomb blast.

UPA Rule and Renewed Aggression:

Decades later, the rhetoric that fuelled the 1982 riots echoed with chilling clarity in a 2021 speech by Rev. George Ponnaiah. Far from being a fringe element, Ponnaiah, a mainstream Catholic priest, openly boasted of the Church’s power to influence elections, claiming the DMK’s victory was "the alms we Christians and Muslims have thrown to you".

He issued a demographic threat, claiming Christians had crossed 62% in the district and would soon be 70%. In a moment of supreme bigotry, he insulted the Hindu reverence for Mother Earth (Bhumadevi), stating, "...we wear shoes. Why? Because the impurities of Bharat Mata should not contaminate us."

He concluded with a horrifying death wish for the Prime Minister and Home Minister. Ponnaiah's speech laid bare the fact that the intolerant supremacist mindset of 1982 was not a thing of the past, but a living, breathing force in the district's religious politics.

In a way one can say that Ponnaiah was the point where the Church was testing the waters if they had to show their naked aggression or not. In the intervening years between Mandaikaadu riots and George Ponnaiah episode, pan-Christian non-BJP political bonhomie has become an all weather tie-up. In the aftermath of 2004's unexpected NDA electoral defeat the attacks on Hindu village temples increased.

The fabricated myth of pseudo-martyr Devasahayam Pillai was floated. It accused Travancore Government of persecuting and martyring a convert. This was pure fabrication. However the Church went ahead and made him a 'Saint' - the first common person in India to be declared a 'saint' by the Catholic Church.

It was given academic credibility through folklore department academicians which in turn were in cohorts with the Church. St. Xavier's College of nearby Thirunelveli district, worked actively in the field studying village Deities and devised methodologies to appropriate the rituals of the village Gods and Goddesses to shrines of Catholic saints.

All these went almost unchallenged by Hindu side.

In 2008 in a Panchayat road the land for which Hindus had donated, a Goddess procession by locals was stopped. The police resorted to brutal lathi charge on the devotees leading to the death of an elderly woman. Almost every day somewhere in the district Hindus would be made to face some humiliations and sometimes with fatal consequences.

Catholic Church launched milk cooperative which became the face of Kanyakumari district's milk suppliers. The agrarian population has been mostly untouched by conversion. The launch of 'Nanjil Milk' by the Church is not direct conversion but creation of a favourable secular disposition towards the Church. Similarly the Protestant missions through the strategy called 'Faith Based Industries' generated Self-Help-Groups to get into traditional cottage industries often taken for granted as Hindu forte.

The RSS also worked in the field. Though unmatched compared to evangelical enterprise, they with their limited resources and steadily dwindling human resources, did make impressive achievements. One such was the role of Seva Bharati the Sangh organisation in making Kanyakumari district a clean district as early as 2004-06 period. They also have made constructive contribution in securing tribal communities their land rights and in organising women welfare groups and SHGs.

In 2008, some of the splinter Hindu groups under Pa. Balasubramanian, an erstwhile RSS worker and Arjun Sampath of Hindu Makkal Katchi accomplished the 'Ghar Wapasi' of more than hundred Christians. This was no mean achievement. This made waves in the district. And there was also the reminder that if this could be achieved when Hindu organisations are together then how much more can be achieved if they all come together.

The Contemporary Battlefield: Subtle Tactics and an Enduring Struggle

Today, the battle for Kanyakumari’s soul continues, but the tactics have evolved. The overt violence of the 1980s has been replaced by more subtle, insidious forms of cultural and demographic warfare. The 2025 Mandaikaadu incident, where the priest was forced from his elephant, encapsulates this new phase. While the priest showed immense grace, the act was perceived as a calculated humiliation, testing the resolve of a Hindu community whose organized unity appears to have waned since its peak in the 1980s.

The Catholic Church, recognizing the power of the Hindu vote bank it helped create, has adopted a more strategic public posture. A key tactic is the propagation of the "sisterhood" fabrication, which posits the Virgin Mary as a "sister" to the Hindu Goddess Bhagavati. This theological demotion exploits Hindu open-mindedness to achieve a "spiritual undermining" from within.

This narrative has found willing allies in Marxist and leftist folklorists who seek to strip Hindu deities of their divinity by reducing them to mere ancestral figures. The 2025 procession incident, however, exposed this "sisterhood" as a calculated illusion that vanished the moment a confrontation arose.

Simultaneously, the Church has methodically expanded its institutional influence. It has established a dairy cooperative that dominates the local milk supply, integrating itself into the economic fabric of the Hindu farming community. Bishop Houses have transformed into hubs for "progressive" workshops, extending their reach beyond religion. Narrative control has become another key weapon.

The novel Marupakkam, heavily promoted by leftist and Christian networks, subtly demonizes Hindus while portraying even extremist Christian elements with a veneer of victimhood, effectively distorting the history of the Mandaikaadu riots for a new generation.

Physical space is also being contested. The small crucifix tower of 1982 has morphed into a formidable shrine, in direct defiance of the Venugopal Commission's recommendation against such constructions in sensitive areas. Hindus have been denied access to a hillock traditionally used for the Karthikai Deepam festival, as it is now part of a Church-owned college.

From Iyya Vaikundar’s Puranic anti-colonialism to Thanulinga Nadar’s political acumen, from Swami Mathurananda’s spiritual revival to Captain Kutty’s intellectual counter-offensives, and from the Hindu Munnani’s mass mobilizations to the ongoing daily struggles for cultural survival, the story of Kanyakumari's Hindus is one of relentless pressure and extraordinary resilience. The challenges today are more complex, the aggression more camouflaged.

The agonizing moment of the lone priest, stripped of his traditional procession and forced to walk, underscores a crucial lesson learned through two centuries of conflict: when Hindu unity becomes merely an episodic, emotional response rather than a continuous, organized, and intellectually fortified process, it leaves the community vulnerable to profound humiliation and dispossession.

The unyielding spirit of Kanyakumari's Hindus has endured, but the future of its unique Dharmic identity hinges on its ability to learn from its long and arduous past.