Culture

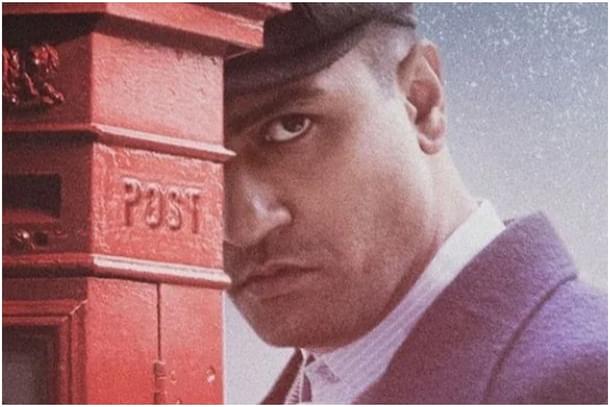

'Sardar Udham' Brings Out The Fierce Patriot In The Man, But Leaves Out Crucial Facts From His Life

Aravindan Neelakandan

Oct 20, 2021, 07:11 PM | Updated 09:54 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Sardar Udham (2021), which tells the tale of the revolutionary who waited for decades to kill the British high official who presided over Jallianwala Bagh massacre, is definitely a vast improvement over most other biopics made about Indian freedom fighters before it. It captures the period as accurately as possible and makes one feel part of the events.

Undoubtedly, the movie has set a new standard for all future Indian biopics.

Udham Singh went by his proclaimed named Ram Muhammad Singh Azad –signifying the religious unity he believed in, as is also shown in the film. However, in the movie, he is also shown as a person inclined towards the Marxist ideology. The Soviet Union, relations with the Communist party, the paranoid fear of Marxism that British officials exhibit and the Marxist ideology itself—all come as a recurring theme in the movie.

In the Nehruvian historiography, which is essentially a soft-Marxist narrative, there is a ‘progressive’ movement from religious nationalism of early revolutionaries to a larger global anti-imperialism. No longer were the later revolutionaries confined to the liberation of India alone but they saw themselves as part of a larger anti-Imperialist struggle spearheaded by Soviet Union. The Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) of Bhagat Singh becomes an important part of this narrative.

While it is definitely true that Indian nationalists were attracted to socialist movements in the West and to the Marxist ideology to an extent, most of them did not convert to Marxism and always held Indian independence as their most important goal; ideological musings only enjoyed a secondary interest.

And despite projection to the contrary, religion and spirituality were always important factors for them – whether one likes it or not.

Not unexpectedly, the movie ignores this dimension. But then there is no point blaming the movie-makers. We have been conditioned to devalue our religious dimension and hide it as much as possible. That said, the movie does bring in references to Sri Guru Gobind Singh. This is done by one of the victims of the eventual Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Here, one needs to talk about this scene.

Let us compare it to the depiction of the same event in Richard Attenborough's Gandhi. Between these two depictions, the one in Sardar Udham is definitely more gory. Perhaps the director thought that was the best way to convey the utter inhumanity of the act. As the scene proceeds one wants it to end. As against this, Attenborough was able to convey the inhuman horror, the beastly nature of the empire's machinery with far less gore. Yet, it left the viewers with a deep sense of pain.

Getting back to religion as an important but a near-invisible component in the entire narrative, let us start with Michael O’Dwyer. The movie shows a scene where the future assassin becomes a house help in his residence and acquaints himself with retired governor of Punjab. Dwyer, in a conversation, states that the educated class in India made trouble while the peasants were happy with the British. This is a secularised version of the view Dwyer actually held.

That the anti-Brahmin views of the man who presided over the Jallianwala Bagh massacre have much in common with the views of today's elite in India should be disturbing, if not surprising:

Sir Michael was suspicious of all Indians, but the Hindu majority most of all. He loathed the educated ‘Hindu Bourgeoisie’ as he liked to call them, believing they had been coddled and needlessly empowered thanks to the recent Morley-Minto reforms. … Brahmins, India’s highest caste, were the worst of the lot: ‘The Brahmin or Kayasth, with his advocate’s training, may make a brilliant speech in faultless English. But it is purely critical and barren of any constructive proposal, for he has behind him neither traditions of rule nor administrative experience.’ … He would later share his classifications with the world, and uncharitable generalisations about Brahmins figured repeatedly: ‘The Mahratta Brahmin is from diet, habit and education, keen, active, and intelligent but generally avaricious and often treacherous.’Anita Anand. The Patient Assassin: A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj, Simon & Schuster UK. Kindle Edition, pp. 52-53

(The Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened a few days after a Sri Ram Navami procession in which Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs participated, breaking the taboos of social stagnation. Gandhi seemed to have made Muslims and Hindus come together to celebrate Sri Ram Navami).

While the day of Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened on 3 April by the English calendar, it was also a meeting – a political gathering, held around the auspicious day of Baisakhi. Brigadier Reginald Dyer, who actually ordered his troops to fire on unarmed people, was even advised to take 100 British and 100 Muslim soldiers with him. Dyer though, had full faith that his soldiers had overcome religious affinities.

In all probability, Udham Singh witnessed Jallianwala Bagh as a young water boy.

Udham himself was inspired by Bhagat Singh, who had forsaken conventional theistic beliefs. But HSRA, despite its secularism, was against proselytizing. One of the first assignments given to Rajguru in the HSRA was the assassination of Hasan Nizami, who was active in the conversion front.

While asserting his name as Ram Muhammad Singh Azad, Udham Singh was asserting a very Indic concept of religious unity that rejected conversions. Unlike Marxism which considered all religions opiate, Indian revolutionaries, even those who flirted with Marxism, opted for a synergy of religious traditions.

Udham Singh had travelled the world not like a student on scholarship but as a worker. He had worked in the Railways of Uganda. He had stayed in Mexico. He had traveled in Europe. He had traveled to Russia and had nursed a sympathy for Bolsheviks, as most Indian nationalists had at that time. He had been in Mexico – in fact, he had entered the United States through Mexico. There, he associated himself with Ghadar Party and worked in various factories, including the Aero plane workhouse. He was the only Indian there who was earning and was called Frank Brazil – a name that entered one of his passports.

After America, he came back to India leaving Lupe Hernandez, his American wife of many years, for good. We still do not know if he had kids. He seemed to have suddenly awakened from the slumber of American comfort and returned to Punjab with Ghadar literature and ammunition, only to be caught by the police and imprisoned for five years.

The movie leaves out the American wife from its narrative. A romantic Indian connection is forged instead.

In her well researched book on Udham Singh, Anita Anand presents a personality of Udham which was different from the moody, ever-brooding persona of Udham that Vicky Kaushal has so skillfully brought to life in the film:

… though he rarely seemed to do any work, he was never short of cash. He drank in pubs, entertaining goras† with tall tales from India; a charming chancer, known to con barmen out of free drinks by pretending to be a member of the Patiala royal family. His ‘Punjabi prince’ persona, one which he had loaned to Pritam many years before, was a hit with the ladies. Fellow pedlars were in awe of his confidence. He was able to romance exotic women while they remained prisoners of their own broken English.Anita Anand, p.231

That actually presents a creative challenge to movie makers - a jolly good person seemingly enjoying pleasures outside while seething with anger within. However, that would be too much to ask from Bollywood biopic-maker who has definitely taken baby steps in terms of delivering a genuine, made-in-India biopic.

It is interesting that the movie never delves into his American past and only shows the Soviet part, which remains mysterious and tentative. Despite his sympathy for the Bolsheviks, by 1937 ‘Udham appears to have dispensed with his reliance on Russian help, and instead looked to America once again’, writes Anita Anand (pp. 236-237).

Superficially a romantic, partying youngster and inside a soul awaiting to avenge the crime against his people—what was Udham Singh's approach to religion?

Was he a Marxist or a hedonistic Charvaka? His letters from prison throw light onto this crucial aspect.

In his letter dated 15.03.1940 which he addressed to Shiv Singh Johal of Gurudwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha at Shephereds Bush, he asked for 'some books in Urdu or Gurmukhi' with a specific instruction, that he did not want 'your Religious Books as I do not believe them nor Mohamedenis.'

On 20.03.1940 in the post script he writes about a 'gentleman' who comes everyday: 'trying me to bring faith in Christianity.' With a caustic humour Udham writes that he might get a good position in government when he went back as he would belong to Church of England and it would also stop both of them wasting time. Then he writes that he had asked the mosque to send him Quran but he doubted if they would send. He goes on to say that eventually, he did not care.

He also wanted Shiv Singh to locate a ‘Quran’ he had given to someone. J.S.Greywal and H.K.Puri in their study of his letters write about this reference to Quran thus:

Some person in East London, who knew both Udham Singh and Shiv Singh was in possession of this 'book' left with him by Udham Singh himself. Probably he had acquired more than one revolver for his premeditated task.Letters of Udham Singh (Ed. J.S.Grewal & H.K.Puri), Guru Nanak University, Amritsar, 1974, p.93

Then this:

I am sitting in the school like a child. I will ask the governor of Prison if he will allow me to see someone from the Sikh Temple. Because the Priest are allowed. Any how if you have someone who can come from your Church please let me know by return So I may ask the Governor. Will be pleased to see my own priest after 21 years. But now as the time is getting nearer day by day and before I leave every body behind I like to see all the Priest I can.

After this, in his letter dated 30 March 1940, he returns the book sent by Shiv Singh whom he addresses him as Jahal, perhaps it was a typo or a deliberate taunt meaning 'fool'. Then this:

I never afraid of dying so soon I will be getting married with execution. I am not sorry as I am a soldier of my country it is since 10 years when my best friend has left me behind and I am sure after my death I will see him as he is waiting for me it was 23rd and I hope they will hang me on the same date as he was

He also states that they should not spend money on his defense and that it be spent on education. Then he asks for Heer Waris Shah – a romantic mystic Punjabi poetry where the human love for the beloved becomes the mystic quest for the Divine. In his letter dated 14 April 1940, he complains that the books were not given to him but were with the prison authorities who might send them back to Shiv Singh. Though he signed for the parcel he had not seen them. He writes:

The governor of the prison is a tough guy he changes his mind every five minutes every other peoples are allowed to read there regilist books they go to Church But I am the only one here in English Constration prison who is the maltreated I know they hate me. But who care about I have seen many before like this genetleman But in any case our Regilist books not to be read unless having bath So I get the bath every other 10 days here. ...I will ask in the Court if the books were prohibited in the prison.

On 5 June 1940 at the Old Bailey Court, London, he burst into a speech which shocked the judge:

I do not care about sentence of death. It means nothing at all. I do not care about dying or anything. I do not worry about it at all. I am dying for a purpose. We are suffering from the British Empire. ... You people go to India and when you come back you are given a prize and put in the House of Commons. We come to England and we are sentenced to death. I never meant anything; but I will take it. I do not care anything about it, but when you dirty dogs come to India there comes a time when you will be cleaned out of India. All your British Imperialism will be smashed. Machine guns on the streets of India mow down thousands of poor women and children wherever your so-called flag of democracy and Christianity flies. ... I have more English friends living in England than I have in India. I have great sympathy with the workers of England. I am against the Imperialist Government. You people are suffering - workers. Everyone are suffering through these dirty dogs; these mad beasts.

His prepared notes read even harsher:

In any part of the world wherever your rotten so-called flag of democracy and Christianity flies you will find only guns, blood, starvation, and filth of the lowest grade. The day has come when the murderous bloodthirsty dogs of Britain must not only give to the Colonies their freedom but also go through some of the torture and pain which they have inflicted upon poor unarmed peoples like my own country people.Emergence of the Image Redact Documents of Udham Singh, (Ed. Avtar Singh Jouhl & Navtej Singh), National Book Organisation, p.190

Today, as Punjab is facing an evangelical onslaught like never before, lines of Sardar Udham Singh alias Ram Muhamad Singh Azad become important. However, we find these lines removed in the movie.

Finally, according to historian and biographer of Udham Singh, Dr. Sikander Singh, as his last day approached Udham meditated, recited 'Japji' and other 'Gurbani' from the 'Sikh Prayer Book' sent by Shiv Singh Johal from Sikh Gurdwara.' (Sikander Singh, p.253). Here are two post-scripts.

Strategic Flexibilities of Theo-Empire:

W.E.S. Holland was an Anglican priest, who visited Udham Singh in the prison and tried to convert him. He made a frantic effort to stop the execution of Udham. In his letter to Amery, the Secretary of State for India, he wrote that he 'began to visit Udham Singh in prison immediately after the murder as part of the pastoral responsibility for Indians in London given to him by the Archbishop of Canterbury.'

After declaring that the trial which he attended 'was scrupulously fair in intention and fact' he appealed for an act of spontaneous generosity which would close the chapter of 1919. He also pointed out to the strategic advantage. While an execution would make Udham Singh a martyr to be admired, a clemency would show the murder 'as an act of isolated underdeveloped fanatic.'

Reginald Dyre died on 23 July 1927. On 27 July his body was taken to All Saints Church at Long Ashton, a village. Though it was supposed to be a quiet service, unexpectedly a large crowd gathered. Rev. John Varley, the vicar of the church, praised Dyer and attacked those who had criticised his action.

A Tamil benefactor of Udham?

Anita Anand points out that one mystery about Udham Singh was that he was never short of money for most of the time in his life:

We know that Indian nationalists like Chempakaraman Pillai, alias Venkat, part of the so-called Hindu German Conspiracy of 1914, were still using Berlin as their base. The Ghadars would have needed men to deliver and collect messages on their behalf. Udham, we know, was only too happy to serve the Ghadars, not only because he regarded it as a noble calling, but also because he needed substantial amounts of cash. ... He appears to have been in a desperate hurry to travel to Germany and Russia in 1934. The urgency may in part have been due to the fact that Venkat had died suddenly in Berlin at the end of May and left numerous loose ends to tie up.Anita Ananda, p.216

Was 'Venkat' one of the sources of money for Udham Singh? It is highly probable and research into secret documents would reveal the facts conclusively.

On the whole, Sardar Udham definitely moves forward in terms of professionalism and technique as well as storytelling. But it is not true to the real Udham Singh or Ram Muhammad Singh Azad, whose life was an interesting mixture of a lot of qualities, warts and all. And one quality that sometimes glows like an ember covered by ashes and in the end bursts out like a volcano, was his patriotism.

The movie has done justice to that.