Defence

The Silent Switch: How China Is Building A Kill Button Inside India’s Critical Infrastructure

Prakhar Gupta

Jul 08, 2025, 09:30 AM | Updated Aug 03, 2025, 09:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In early 2024, Manipur became a hot topic on Chinese social media platforms.

The conflict between the Meitei and Kuki communities in Manipur had already claimed hundreds of lives by then and displaced tens of thousands, but what caught the attention of Chinese netizens was something else entirely. In corners of Douyin and WeChat, a bizarre phrase began to circulate: “There’s a little China in India that holds the six-star red flag, does not speak Hindi, and refuses to marry Indians.”

The claim was outrageous, yet it spread with unsettling speed. Chinese social media accounts, some with no prior history of posting political content, began sharing photos of Manipur, pairing them with this strange assertion.

Not long after, the narrative crossed platforms.

A Chinese-language YouTube channel called Earth Story speculated about Manipur’s future and its “independence” from India. Though the video had limited views, it was subtitled in Hindi and English, allowing it to move easily across language barriers.

Soon after, an X account named jostom shared the video. The account had few followers, mostly posting scenic images and motivational quotes. But it didn’t exist in isolation. It was part of a broader pattern, a cluster of nearly identical accounts, created around the same period, now active and amplifying the same messaging about Manipur.

The “Little China” narrative soon seeped into Indian digital spaces. Posts translated clumsily through AI from Mandarin to Hindi and Meitei began appearing on WhatsApp groups, local forums, and fringe news blogs. Messages questioned India’s sovereignty over Manipur, called the ethnic clashes a result of India's oppression, and pushed the idea that the region had more in common with China than with India.

Only later did researchers begin to piece together the scope and intent of the campaign. Analysts at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), working with Taiwan's Doublethink Lab, identified it as part of a larger effort by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to interfere in India’s domestic affairs. The structure, timing, and execution mirrored previous CCP-linked disinformation operations.

Meta’s own threat reports soon confirmed that coordinated networks originating from China had been active for months. The same infrastructure had been used to target the global Sikh diaspora. In Manipur, it followed a similar playbook: inflammatory content, artificial amplification, and psychological cues to deepen local mistrust of the state.

What emerged wasn’t just a disinformation campaign. It was a rehearsal. A test of how fast, how far, and how deeply a false narrative could penetrate India's fragmented information landscape, and how quickly could India respond to fix the vulnerabilities.

And it worked.

The campaign showed how a narrative could be seeded, shaped, and fed into a volatile domestic issue in India with plausible deniability.

While China’s attempts to deepen Manipur’s ethnic divide played out in full view, it has also been waging quieter, sustained campaigns of sabotage away from public attention. These range from recent export restrictions aimed at undermining India’s manufacturing ambitions to something far more covert: the targeting of critical infrastructure.

For years, Chinese state-linked actors have been quietly mapping, probing, and, in some cases, breaching the digital systems that keep India running, with the most troubling focus being the methodical infiltration of India’s power grid.

The grid becomes a battleground

In recent years, one of the clearest indications that India’s critical infrastructure was being quietly targeted by Chinese cyber operators emerged in early 2021.

That was when Recorded Future, a cybersecurity intelligence firm based in the United States, revealed that a Chinese state-linked hacking group, later identified as RedEcho, had infiltrated key systems within India’s power grid.

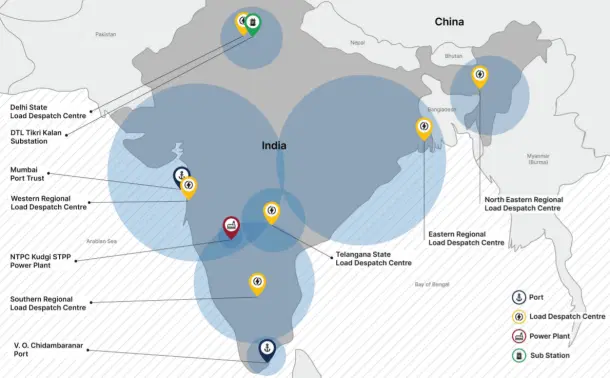

Over the course of several months, this group had managed to quietly establish digital links to at least ten of India’s most sensitive power-related entities. These included four of the country’s five Regional Load Despatch Centres, or RLDCs.

To understand the seriousness of that: RLDCs are not ordinary administrative units. They are the central control rooms responsible for balancing how much electricity is produced and how much is used, second by second, across massive regions of India. If one were disrupted, the ripple effects could lead to widespread outages and economic paralysis.

But the RLDCs weren’t the only targets.

The hackers were also found to be inside systems linked to a major thermal power station, two large shipping ports, and several high-voltage substations, critical infrastructure that enables electricity to travel across state lines and into homes, hospitals, airports, data centres, and military bases.

These systems form the invisible spine of India’s economy. That someone was poking at them, quietly, and with skill, was a red flag not just for cybersecurity experts, but for national security agencies.

And this wasn’t happening in a vacuum. The timing of the breaches coincided with a dramatic escalation in tensions along the disputed border between India and China.

In mid-2020, both countries had moved troops into forward positions in Ladakh. By June of that year, the standoff had turned deadly in the Galwan Valley, resulting in the first combat fatalities between Indian and Chinese troops in more than four decades.

Amid the military build-up and failed rounds of diplomacy, the digital intrusions took on a different tone. They didn’t look like ordinary espionage. They looked like preparation, laying digital landmines that could be triggered if the conflict deepened.

Then, in 2022, a second wave of intrusions came to light.

This time, the pattern repeated, but with a new set of targets. Seven State Load Despatch Centres (SLDCs), which handle electricity distribution within states, were found to be compromised. Also hit were the Indian operations of a global logistics firm and, more worryingly, the country’s national emergency response system.

The breaches have deepened fears that China’s cyber strategy may go beyond disrupting infrastructure to actively undermining India’s ability to respond in a crisis.

While some of the technical tools resembled those used in the earlier campaign, the geography added new weight to the concern. According to Recorded Future, "this targeting has been geographically concentrated, with the identified SLDCs located in North India, in proximity to the disputed India-China border in Ladakh."

The target list, in other words, was starting to look like a map of strategic interest.

These breaches raised uncomfortable questions about whether some disruptions in the power grid had already served as warning shots.

In October 2020, a massive power outage plunged Mumbai. Days later, authorities confirmed the discovery of malware at a State Load Despatch Centre near Padgha, which controls power supply to the region.

The incident took place in the middle of the Ladakh standoff, at a time when tensions between India and China were arguably at their highest in decades following the deadly Galwan Valley clash in June that year.

While the government did not formally attribute the outage to a cyberattack, analysts at Recorded Future found the timing, location, and nature of the malware consistent with a broader Chinese campaign targeting India’s critical infrastructure.

What made these intrusions particularly alarming wasn’t just the kind of institutions being targeted, but intention with which these breaches were carried out.

This wasn’t a smash-and-grab job. The infected systems continued to communicate with command-and-control servers linked to the attackers for weeks, even months. These weren’t mere scans or superficial probes. Malware had been deployed. Systems were being studied. Internal configurations and workflows were likely documented.

And most troubling of all was that there was no immediate sabotage. The malware sat quietly, awaiting orders. For analysts who study nation-state cyber operations, that behaviour is telling. It suggests pre-positioning, or planting the tools needed to carry out a disruption, but waiting to activate them until the strategic moment is right.

In military terms, it’s the difference between loading artillery and pulling the trigger. And in cyber terms, it’s often far harder to detect, until it’s too late.

Inside the Chinese toolkit

At the heart of the Chinese operation was a tool called ShadowPad, a sophisticated piece of malware quietly used by multiple Chinese state-linked hacking groups. Over time, it spread across the Chinese cyber-espionage ecosystem, shared among Ministry of State Security (MSS) contractors and units affiliated with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). It has since become a signature tool of China’s cyber strategy.

ShadowPad isn’t a virus in the traditional sense. It’s what cybersecurity experts call a modular backdoor, a kind of software that creates a hidden opening into a system for long-term remote access. But unlike simple intrusions, ShadowPad is designed to evolve. Once installed, it can be updated with new components that allow its operators to collect system data, steal credentials, or deepen their access, all without detection.

What set this campaign apart was the way ShadowPad was deployed. The attackers didn’t need to breach firewalls directly or rely on phishing emails to employees and contractors to enter the system.

Instead, they exploited internet-connected devices that were already embedded inside every part of India’s power infrastructure, like unsecured surveillance cameras and digital video recorders (DVRs).

These devices, common across industrial facilities for routine monitoring, are often left running outdated software or still using default passwords. Crucially, many are connected to internal networks for convenience, while also being exposed to the internet for remote access.

That made them ideal stepping stones. They are not critical enough to be tightly guarded, but networked deeply enough to serve as launch points. Once compromised, these devices allowed attackers to quietly plant ShadowPad.

Once inside, the attackers used a tool called Fast Reverse Proxy (FRP) to maintain their connection. FRP is an open-source utility commonly used by IT administrators to make internal services, like dashboards or local applications, accessible remotely. It works by creating a secure, outbound connection from a device inside the network to an external server.

In everyday use, it’s a convenience tool. But in this case, it was weaponised. By configuring FRP on compromised DVRs and other devices, the attackers could reach deeper into the network from the outside, bypassing firewalls, avoiding detection, and interacting with systems that were never supposed to be visible to the internet.

To avoid detection, the attackers disguised the malware’s communication by using what appeared to be legitimate security certificates or digital credentials that verify the identity of a website and encrypt the information flowing to and from it. Every time you see a padlock icon in your browser, you're seeing one of these in action.

By mimicking a trusted certificate, at times even one purporting to be from Microsoft, the attackers made their traffic appear indistinguishable from regular web activity. It blended in, silently passing through firewalls and antivirus filters designed to flag suspicious connections.

But the concealment didn’t stop there. Many of the servers used to control the malware, known as command-and-control servers, weren’t based in China. Instead, they were hosted on hacked computers in countries like Taiwan and South Korea, systems repurposed without their owners’ knowledge. This tactic made the digital trail harder to follow and gave the campaign a useful layer of deniability.

To cybersecurity professionals, the methods used left little doubt that this was the work of a state-sponsored group. The technical sophistication, the careful concealment, and the long-term access all pointed to what experts classify as an advanced persistent threat. These are operations designed not to cause immediate damage but to quietly establish access and hold it over time.

Why the lights stayed on

There was no power failure traced back to these intrusions. No systems were locked or held for ransom. No visible sabotage occurred. On the surface, it looked like nothing happened.

But that, cybersecurity experts say, is what makes it significant.

The objective wasn’t to cause immediate disruption. It was to gain access and hold it. These intrusions appear to be about pre-positioning or establishing a presence inside key systems that could be used later, if circumstances demand it. In a moment of crisis, such access could allow operators to cut power, slow emergency response, or interfere with logistics.

This kind of strategy is not unique to India. In 2023, the US exposed a Chinese state-backed group known as Volt Typhoon that had quietly infiltrated power, water, and communications systems across multiple American states.

Like the Indian campaign, Volt Typhoon caused no immediate damage. Instead, US intelligence agencies said Chinese Volt Typhoon operators were "pre-positioning themselves on IT networks to enable lateral movement", ready to strike if geopolitical tensions, such as a confrontation over Taiwan, escalated.

China does not intend to exploit its access to India’s critical infrastructure immediately. But by embedding itself quietly in advance, it secures a strategic edge. If tensions escalate, the ability to disrupt civilian systems is already in place. The malware may lie dormant indefinitely, yet its mere presence alters the calculus of any future conflict.

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.