Defence

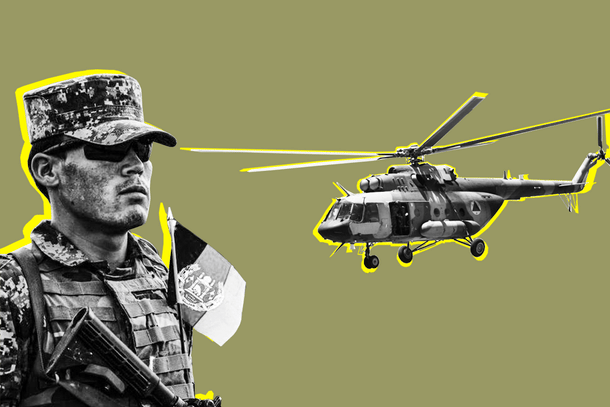

The US Spent Billions Building The Afghan Military. Why Did It Collapse So Quickly?

Swarajya Staff

Aug 17, 2021, 01:54 PM | Updated 03:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On 8 July, a little more than a month ago, President Joe Biden said the United States had provided "all the tools, training, and equipment of any modern military" to the Afghan security forces, as he told the world that the withdrawal of troops from the country will be "secure and orderly".

"Speed is safety," Biden said, talking about the necessity to move US forces out of Afghanistan swiftly and completing the process by 31 August.

That the Afghan military could collapse within weeks was not something he or others in the security establishment in Washington had anticipated.

It was believed that the forces trained by the US and its allies over 20 years would be able to hold off a Taliban takeover long enough for the Ashraf Ghani government to reach a negotiated solution with the group, if not defeat it. However, as Taliban fighters overran more than a dozen provincial capitals in a week and entered Kabul on 15 August with little or no resistance from government forces, the world was caught off guard, and it was clear that the Afghan military had simply melted away.

When it came to halting the Taliban's advances, the billions poured in by the US and its allies in weapons, equipment and training for the Afghan military added up to nothing. The Afghan National Army, an institution built to outlast the war with the Taliban, collapsed even before the US could completely withdraw from the country, ending a two-decade long effort to raise a fighting force that could take over the reins of security from foreign troops.

The speed with which the Afghan military collapsed stunned the world, which was not ready for this eventuality, and led to the scenes eerily reminiscent of the US' humiliating withdrawal from Saigon in 1975.

There is no simple explanation for the spectacular collapse of the Afghan military. It was a result of multiple factors — mismanagement and chronic corruption, disillusionment with the government, ethnic and tribal loyalties, and, most importantly, a crisis of confidence in the Afghan Army to fight off the Taliban in the absence of US military and intelligence support.

Former US President Donald Trump's February 2020 agreement with the Taliban calling for a full American withdrawal from Afghanistan, which the Biden administration decided to adhere to, left the Afghan military without the crucial air power and battlefield support which it had learned to rely on, and hit their morale. The Afghan Army's reliance on US close air support and reconnaissance and intelligence gathering meant that it never became an independent fighting force, a role that the US and its allies were preparing it for since at least 2014.

Early losses to the Taliban in the fighting season, which lasts from April to October, combined with the abrupt departure of US troops, undermined the resolve of the Afghan military to confront highly motivated Taliban fighters. The parlous state of the Afghan government and its isolation after the US-Taliban deal did not inspire much confidence either.

Mismanagement and rampant corruption within the military and the government also played a part in the disillusionment of Afghan soldiers. In many cases, supplies such as food and ammunition did not reach soldiers on time and in the right quantities and, in some cases, soldiers had not been paid in six to nine months. It is no surprise that in a country where many joined the Army for money due to lack of opportunities in other areas, patriotism alone couldn't keep them going, especially when they were required to put their lives on the line.

In the initial months of the fighting, the Afghan government rejected the idea of consolidating forces and tried to hold territory, even areas that were going to be impossible to defend, through a web of checkpoints and outposts scattered across the country. This strategy resulted in units being dispersed throughout the country. The result was that these units were unable to reinforce one another. It also strained the lines of communication of the Afghan military and gave the Taliban the opportunity to interdict these supply lines.

As the fighting progressed, many outposts, under attack from the Taliban, were left without resupplies and reinforcements for days, breeding discontent among the soldiers who felt abandoned.

The "badly paid, ill-fed and erratically supplied" soldiers were unwilling to risk their lives fighting the Taliban for their commanders and the government, who many saw as corrupt and selfish. While most may have preferred the government in Kabul over the Taliban, these realities made it not worth fighting for many in the Afghan security forces.

The Taliban capitalised on the uncertainty created by the ongoing US withdrawal and the disillusionment of the Afghan forces, offering them deals — safe passage home and, in some cases, even cash, in exchange for surrender and leaving behind equipment provided by the US. It involved tribal elders and used personal, local and ethnic ties, which outweigh loyalty to the state for a large number of Afghans in the rural areas, to get soldiers to surrender and abandon their positions without firing a shot.

Similar deals between local commanders and the mujahideen had played a big part in the collapse of the Communist state in 1992.

While some were interested in money, others saw the Taliban's offer as an opportunity to save their lives and end up on the winning side. The latter became increasingly appealing for many Afghan soldiers as momentum swung towards the Taliban and provincial capitals started falling.

As the Taliban's victory started looking inevitable in early August, more Afghan soldiers, convinced that the government in Kabul would not back them up, surrendered without a fight. A series of negotiated surrenders, for instance in Kunduz, Herat, Kandahar and Helmand, resulted in a large number of Afghan soldiers and commanders laying down their weapons and retreating. Like a domino effect, these surrenders encouraged more soldiers to follow suit, and made the Taliban's effort to hollow out the Afghan security forces successful.

“Brother, if no one else fights, why should I fight?," an Afghan soldier in Kunduz was quoted as saying to his commander.

In some cases, deals were struck at higher levels. In the southeastern province of Ghazni, for example, Governor Mohammad Daud Laghmani allegedly struck a surrender deal with the Taliban for safe passage out of the war zone, believing defeat was unavoidable. Some have gone as far as suggesting that the orders to put down weapons came from Kabul. While this may be an exaggeration, many such cases — deals made at high levels of government and military — are likely to come to light after the dust of war has settled.

Summary killings of Afghan Special Forces commandos, the assassination of other military personnel such as air force pilots and the cold-blooded murders of civilians who stood up to the Taliban deterred those who were determined to put up a fight. Tailored propaganda — a deluge of videos of surrendering Afghan soldiers, pictures of captured Afghan and US equipment and text messages — was delivered directly to cell phones (over 70 per cent of the Afghan population has access to cell phones) to create panic.

The terror campaign and propaganda aided the Taliban's psychological-warfare effort by reinforcing the message that Kabul was incapable of providing security to Afghans. It worked — after all, the Taliban had learnt the art of information operations from one of the best practitioners in the world, the Pakistani state.