Defence

Indus Waters Treaty: Why India Can’t Weaponise Water Against Pakistan Yet

Swarajya Staff

Apr 24, 2025, 12:14 PM | Updated 05:07 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In response to the Pahalgam terror attack, in which Pakistani terrorists killed 26 Indians — mostly tourists — the Government of India has announced that it will hold the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance until Pakistan takes decisive action against terrorism.

This move has ignited hopes among some Indian citizens that blocking water flows to Pakistan could cripple its agriculture-dependent Punjab region, which relies heavily on canals fed by the Indus river system.

India’s decision marks a significant escalation in tensions, but the practical impact on Pakistan remains uncertain due to logistical, geographical, and infrastructural constraints that limit India’s ability to weaponise water in the short to medium term.

Indus Waters Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was brokered by the World Bank and signed in 1960 by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani President Ayub Khan.

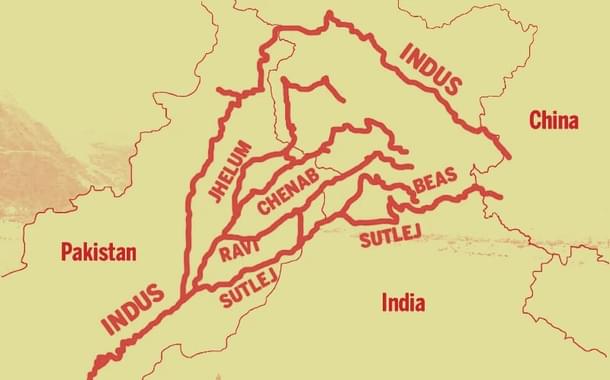

The treaty divides the six major rivers of the Indus basin into two categories:

Eastern Rivers: Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej – allocated to India for exclusive and unrestricted use, including for purposes such as irrigation, domestic supply, and hydropower generation.

Western Rivers: Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab – largely allocated to Pakistan, but India is permitted limited use of their waters for non-consumptive needs (like hydropower generation, navigation, and domestic use), as well as restricted agricultural usage and small-scale storage, provided these projects do not adversely affect the flow to Pakistan.

The treaty has survived multiple wars and periods of extreme tension between the two countries. While hailed as a model for transboundary river cooperation, it has also come under scrutiny in recent years, especially in India, where there have been growing calls for its reassessment in light of continued cross-border terrorism originating from Pakistan.

India believes it has been overly generous under the treaty and that it should explore fuller utilisation of its entitlements under the IWT framework.

Over the last decade, India has also signalled its intent to leverage the IWT as a tool to pressure Pakistan over cross-border terrorism.

In November 2016, for instance Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that no water from the Eastern Rivers, allocated to India, would flow into Pakistan. Following the 2019 Pulwama attack by the Pakistani terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed, India accelerated water projects to fully utilise Eastern River flows, ensuring no surplus reached Pakistan.

In August 2024, India formally notified Pakistan of its desire to review and modify the IWT, citing changed circumstances. The recent announcement to hold the treaty in abeyance reflects India’s mounting frustration with Pakistan’s inaction on terrorism and its strategic shift toward exploring punitive measures through water control.

Limited Options For Immediate Impact

India’s suspension of the IWT has fuelled expectations of choking Pakistan’s water supply, but practical constraints make this challenging in the short to medium term.

The Western Rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab—account for over 80 per cent (117 BCM) of the Indus basin’s annual flow, forming the backbone of Pakistan’s agriculture, particularly in Punjab. However, the geography and topography of these rivers severely restrict India’s ability to construct large-scale storage or reservoirs.

The Indus and Chenab rivers flow through steep, narrow gorges in the Himalayan region, particularly in Jammu and Kashmir, where the terrain is characterized by high gradients and rocky landscapes. These conditions make it technically unfeasible to construct large reservoirs capable of holding substantial volumes of water, as flat land for such projects is scarce and the geological stability of the region is precarious.

For instance, the Indus River’s upper reaches in Ladakh are confined to deep valleys, rendering dam construction costly and risky due to potential seismic activity.

The Jhelum River, while having a milder gradient in the Kashmir valley, presents its own challenges: any large reservoir would inundate vast areas of fertile land and densely populated regions, such as Srinagar, causing catastrophic damage, displacing communities and submerging critical infrastructure—an unacceptable cost.

Public demands to stop water flows to Pakistan overlook the scale of such an endeavor.

Since India already utilizes nearly all Eastern River flows, any blockade would involve restricting the Western Rivers’ 117 BCM. This could be achieved by storing the water or diverting the rivers, but both options are logistically and financially daunting.

Storing 117 BCM annually would require monumental infrastructure. This volume could inundate 120,000 square kilometers to a depth of one meter each year, equivalent to flooding the entire Kashmir Valley to seven meters in a single year.

In reservoir terms, it would necessitate at least 30 reservoirs the size of the Tehri Dam, which holds 4 BCM. Constructing a single Tehri-sized dam takes a decade, so even if India began building 30 reservoirs immediately, impoundment would not start for at least another 10 to 12 years, leaving Pakistan unaffected in the interim.

Finding land for such reservoirs in the densely populated Himalayan region is nearly impossible, and sustaining the blockade would require 30 new reservoirs annually—an infeasible proposition, explains Iftikhar A Drabu, a civil engineer with decades of experience in the hydro sector, in this article for the Observer Research Foundation. ]

Diverting Western Rivers Is Equally Impractical

Diverting the western rivers to alternative destinations is equally impractical due to geographical realities. Redirecting even one river, such as the Chenab, would require constructing a man-made channel spanning hundreds of kilometers across rugged Himalayan terrain, crossing multiple river basins, and navigating elevation changes.

Such a project would demand unprecedented engineering feats, would cost billions of dollars, necessitate acquiring thousands of hectares of land in densely populated or ecologically sensitive areas, that would face insurmountable challenges.

Most importantly, any such project would take decades to complete. Navigating the bureaucratic maze of approvals, addressing protests, and managing the environmental fallout would delay progress. Even with a concerted national effort, the sheer scale of the undertaking—spanning planning, construction, and stabilisation—would stretch across decades, leaving Pakistan’s water supply unaffected for generations.

Fast-tracking run-of-the-river dams or small storages could enhance India’s water utilisation but would not significantly reduce Pakistan’s supply for decades.

But India’s lack of a cohesive strategy for western river development, coupled with a cautious approach to avoid escalation in the previous decades, has left it unprepared to swiftly capitalise on the IWT’s suspension, further limiting its options.

For instance, the treaty allows India to develop run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects and limited storage facilities, capped at 3.6 million acre-feet, on the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers.

However, India has significantly underutilised these entitlements due to a combination of Pakistan’s technical objections, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and a lack of planning despite the rhetoric. As of 2023, India has irrigated only 642,000 acres in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, far below the 1.34 million acres allowed by the treaty.

India’s suspension of the IWT may have bolstered its diplomatic position, but the stark reality is that disrupting Pakistan’s water supply remains unattainable for now.