Economics

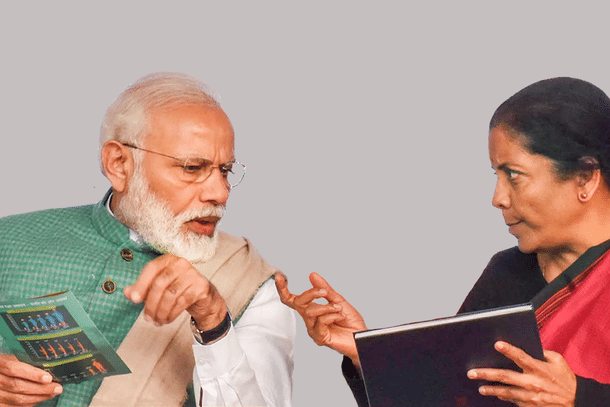

Economic Survey Bats For Market Economy, Shows How Government’s Intervention Can Do More Harm Than Good

Arihant Pawariya

Jan 31, 2020, 04:16 PM | Updated 04:15 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

It is no news to anyone that India fares poorly in giving economic freedom to its citizens and business firms. Two key indexes in this regard establish the poor standing of India.

In the Index of Economic Freedom brought out by The Heritage Foundation, Indian economy ranked 129th among 186 countries. In the Index of Global Economic Freedom by Fraser Institute, India ranks 79th among 162 countries with 108th rank in business regulation.

The Indian state is not only involved in running businesses that it has no business running but also intervenes in markets quite frequently. Though the intentions are honest and good, more often than not, the interventions succeed in making matters worse.

2019-20 economic survey lists four such interventions by the government of India which has done more harm than good and hurt the ability of the markets to support wealth creation, and has led to outcomes opposite to those intended.

First is frequent and unpredictable imposition of blanket stock limits on commodities under Essential Commodities Act (ECA). The survey notes that such steps neither bring down prices nor reduce price volatility. Rather, they enable opportunities for rent-seeking and harassment.

The survey takes three examples for consideration — a) imposition of stock limits on dal in 2006-Q3; b) sugar in 2009-Q1 and; c) onions in September 2019. In each of these cases, the intervention spiked up the volatility of the wholesale and retail prices whereas the objective was to ease pressure on prices.

The act is anachronistic as it was passed in 1955 in an India worried about famines and shortages; it is irrelevant in today's India and must be jettisoned, the survey argues.

Due to ECA, four distortions take place in the agriculture market — a) It weakens development of agricultural value chain; b) reduces producer’s profit; c) Inhibits development of vibrant commodity derivative markets; d) reduces incentive to invest in storage. All these increase price volatility in the market thereby reducing consumer welfare.

Second is the regulation of prices of drugs through the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO) 2013. The survey notes that this led to the increase in the price of a regulated pharmaceutical drug compared to that of a similar drug the price of which was not regulated.

While the DPCO aimed at making drugs affordable, it ended up achieving the opposite. "The prices increased for more expensive formulations than for cheaper ones and those sold in hospitals rather than retail shops," shows the survey’s analysis. The very objective of the DPCO stood destroyed.

The survey’s analysis show that the prices of drugs that came under DPCO, 2013 increased on average by Rs 71 per miligram (mg) of the active ingredient, but, for drugs that were unaffected by DPCO, 2013, the prices increased by only Rs 13 per mg of the active ingredient.

For drugs sold at hospital and which came under DPCO regulation, price increased by Rs 99 per mg but for drugs not under DPCO, price increase was only Rs 25 per mg. As far as drugs sold at retail outlets are concerned, for those under DPCO, prices increased by only Rs 0.23 per mg while for those not under DPCO, prices decreased (yes, decreased!) by Rs 1.49 per mg.

Basically the act helped achieve the opposite. As the survey concludes, DPCO "increased prices by about 21 percent for the cheaper formulations (i.e, those that were in the 25th percentile of the price distribution). However, in the case of costly formulations (i.e., those that were in the 99th percentile), the increase was about 2.4 times."

Third bad intervention is government policies in the foodgrain markets. The survey says that this has led to the "emergence of Government as the largest procurer and hoarder of foodgrains – adversely affecting competition in these markets."

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) has overflowing buffer supply — more than it needs, and it has to pay up for this humongous food subsidy burden and what does it achieve? It only helped create divergence between demand and supply of cereals.

Moreover, this is the reason why crop diversification remains a dud because farmers keep producing crops that the FCI pays good monies for rather than growing what the market needs.

Currently, we are at a stage where the consumption of cereals (in both rural and urban areas) has been constantly declining since the last two-and-a-half decade due to rise in incomes, the production of wheat and rice (constitute more than 80 per cent of cereals) is constantly increasing and the biggest incentive for this has been continuous increase in their minimum support price).

The survey recommends that everyone will be better off if the government gives direct investment subsidies and cash transfers to farmers which do not interfere with their crop pattern decisions.

Fourth bad intervention has been debt waivers. The survey analysis shows that "full waiver beneficiaries consume less, save less, invest less and are less productive after the waiver when compared to the partial beneficiaries”.

"The share of formal credit decreases for full beneficiaries when compared to partial beneficiaries, thereby defeating the very purpose of the debt waiver provided to farmers," the survey notes.

As action points for policy-makers, the survey has listed various acts which have the potential to create distortions in the markets and thus need to be amended and repealed. These are Factories Act, 1948, ECA, 1955, FCI Act of 1965, Land Acquisition Act of 2013, etc.

Arihant Pawariya is Senior Editor, Swarajya.